In the very first years of the Soviet Union’s existence, Ukrainian Bolsheviks played an important role in building what became the world's largest ever state.

And it was people from Ukraine itself who engaged in the ‘Ukrainization’ that aimed to replace the Russian language and culture there during the Stalin years. Although this process was officially curtailed in the late 1930s, it continued by inertia for many more years.

As a result, Soviet policy allowed the Ukrainian SSR to become a fairly independent entity with its own national elite and intelligentsia, which opened the path to independence. Moreover, many Party officials from Ukraine held key positions in the USSR right up until its collapse.

Here, RT seeks to explore what influence Ukrainians had on the Soviet Union’s development and how Kiev managed to carve out for itself a high degree of independence.

Secret pages

Although born in the very center of Ukraine, Leonid Brezhnev preferred not to talk about his nationality. Joseph Stalin considered him a Moldavian. Until the 1950s, he had passed himself off as a Ukrainian and, after that, as a Russian, according to documents. However, former French President Valery Giscard d'Estaing, in his memoirs ‘Power and Life’, wrote that his friend Edward Gierek, de facto ruler of Poland for a decade, had told him that Brezhnev's mother was Polish.

“Edward Gierek was a personal friend of Brezhnev’s. He informed me (although I cannot vouch for the authenticity of this information, since our intelligence service did not have a single undercover agent in the Soviet Union) that Brezhnev's mother was Polish. Brezhnev hid this because Russians tend to treat Poles with sarcasm and contempt. Nevertheless, Polish was his native language, and he often spoke Polish with Gierek on the phone.”

Even now, many pages in the history of the Soviet Union remain a mystery. One of these concerns the ethnic composition of the country’s leadership.

Such information was not published by the Party’s Central Committee until 1989, and biographies of members of the governing bodies during the entire Soviet period were not released until 1990, just before the dissolution of the USSR. All of these documents confirmed that many of its statesmen, politicians, diplomats, as well as military and intelligence officers, had been born in Ukraine. However, information about their ethnic origin was often omitted.

Also, many of those who originated from Ukraine were registered as ‘Russian’ or simply as ‘Soviet’. This is why it is so difficult to assess the full scope of political influence Ukrainians had on the decision-making process in the Soviet Union.

It is true that Ukrainians contributed a great deal to building socialism. If we round them all up, we see that there had always been very large numbers of people from Ukraine in the top tiers of power.

Two of them, Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev, ruled the country as general secretary of the Communist Party’s Central Committee. The country’s final ruler, Mikhail Gorbachev, was the descendant of Ukrainian peasants who had moved to Stavropol.

Kliment Voroshilov and Nikolai Podgorny were both Ukrainians who served as chairmen of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, while quite a number of Ukrainians served at various times as deputy chairmen, including Demyan Korotchenko, Mikhail Grechukha, Ivan Grushetsky, Alexey Vatchenko, and Valentina Shevchenko. Dozens of Central Committee secretaries and Politburo members, as well as members of the All-Union government were also Ukrainian. There were also Ukrainians at the helm of the KGB – for example, Vladimir Semichastny, who co-organized the successful coup against Khrushchev in October 1964.

A state within a state

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was managed by local elites, which is completely at odds with the modern myth of Ukraine having been an ‘oppressed nation’ in the Soviet Union. Moreover, so many Ukrainians held key positions in the Soviet government that any allegations made by the present-day Ukrainian authorities about the Ukrainian SSR struggling under the yoke of the Russian SFSR and being de facto Soviet Russia’s colony simply don’t have a leg to stand on.

On the contrary, by the 1950s, the Ukrainian SSR had become a full-fledged statelet that had its own constitution and flag and even parliament. In fact, its structure mirrored that of the government of the Soviet Union itself. Ukraine’s policy was determined by the Communist Party of Ukraine with the Politburo being its highest body of power; its legislative branch was represented by the Supreme Council (this later became the Verkhovna Rada); and executive power was wielded by the Council of Ministers.

The truth is that Soviet Russia had none of the above-listed privileges. The All-Union government allowed other republics to have their national branches of the Communist Party and national Academies of Sciences, but it did not permit this for Russia. The Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic had no government of its own. Joseph Stalin made sure it never did for fear that an empowered Russia might grow to challenge the All-Union government. This policy was so severe that in 1949 a number of senior officials from Leningrad were executed, exiled or imprisoned on trumped-up charges of treason for their intention to create the Communist Party of Russia. This became known as the Leningrad Affair.

Thus, attempts to misrepresent Soviet Russia as a colonial power in charge of the other republics in the USSR are very misguided. Other republics even enjoyed more autonomy. For example, the Belarusian SSR and Ukrainian SSR had their own foreign policy agencies and their own missions at the United Nations from 1945, while Russia did not. This is an unprecedented level of autonomy for a republic that is part of a larger state. For example, it is not something granted to Scotland by the United Kingdom.

Indeed, not so many of the present-day nation states in Europe can boast they were actually co-founders of the UN.

Tackling the challenges

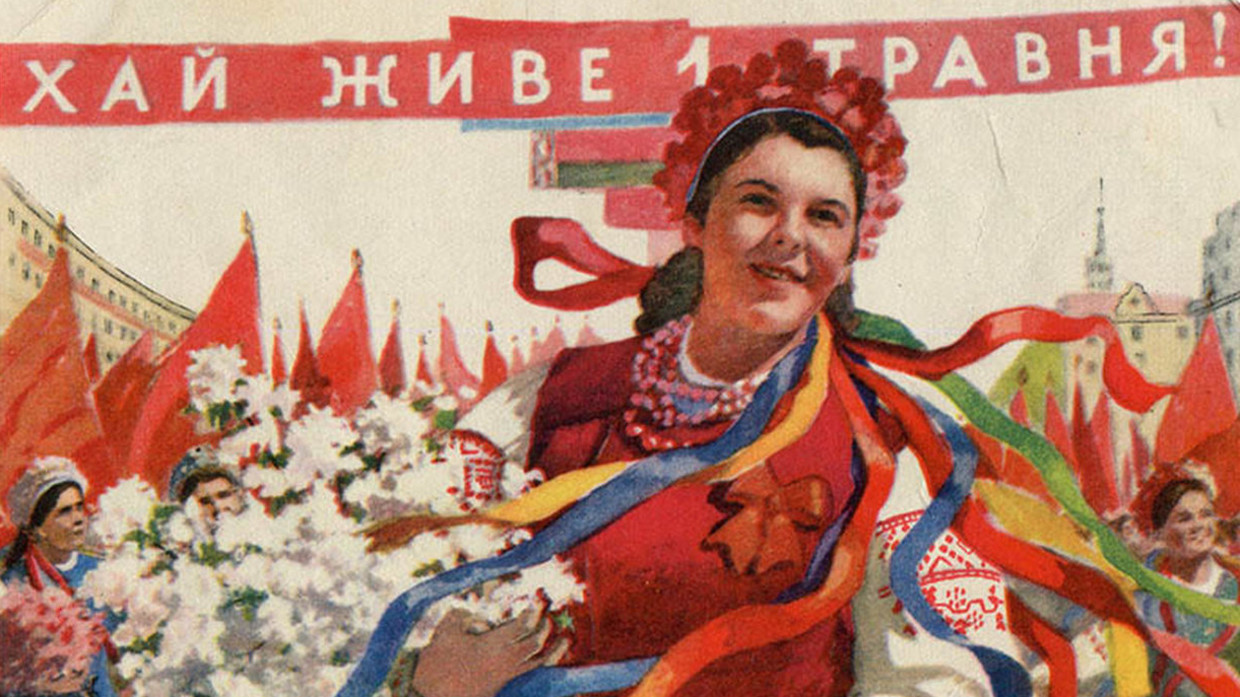

Each Soviet Socialist Republic, including Ukraine, had its national language recognized as official – for example, Soviet currency bills stated their value in all of the national languages. More importantly, the republics were governed by locals. It was through the collaboration of the local elites and the All-Union government that a policy of indigenization, or nativization, was promoted from the 1920s. In the case of Ukraine, it was the ‘Ukrainization’ project.

The idea was to kill two birds with one stone: promote the Communist ideology and to preempt any possible nationalist movements in the republics by giving them privileges and powers. Since local nationalists were unavoidably part of the republics’ governments, nativization was perceived by the Communists as a viable solution to win them over and encourage them to cooperate. Another serious threat was the White movement.

In 1926, Odessa’s population consisted of 160,000 Russians and 73,000 Ukrainians. Kharkov, which was at the time the Ukrainian SSR’s capital city, had 154,000 Russians and 160,000 Ukrainians. Back then, the criteria for establishing one’s nationality were quite loose: sometimes, it was enough to say where a person’s household was located while native language could have been disregarded.

In order to build a new socialist state, the Bolsheviks decided to nip any potential resistance in the bud by supporting Ukraine’s culture and downplaying Russia’s. At that time, many peasants were migrating to the cities in search of a better life. Since they had no roots there, they were a suitable target for the Bolsheviks’ nativization program.

To promote this agenda, they officially proclaimed a policy of indigenization designed to remove ‘vestiges of nationalism’ at the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party in April 1923. The policy implied the promotion of local languages and cultures, as well as the formation of national elites.

The main goal of the campaign was to replace the Russian culture and language in the Soviet republics with local cultures and languages, which was touted as a fight against the ‘Great-Russian chauvinism’ inherited from Russia’s imperial past.

How the steel was tempered

The Bolsheviks effectively stated the need to remedy the consequences of the ‘Russification’ policies pursued by the Russian Empire in order to facilitate the process of building socialism. For that, they nurtured local elites, gave official status to their languages and financed the spread of culture and printed media in these languages. Thus, the Belarusians and the ‘Little Russians’ (Ukrainians) – two ethnicities that had been at the core of the Russian nation – started to shape into ‘independent’ nations pursuing their own ideologies within borders that had never previously existed.

The ‘Ukrainization’ policy was supervised by local officials. In 1924, the main ideologue and mastermind of the ‘Ukrainian nation’, historian Mikhail Grushevky, returned to Kiev with the Bolsheviks’ permission. He devised and implemented a method of widespread promotion of the Ukrainian language through the secondary education system.

At the same time, linguists were tasked with developing a literary form of the Ukrainian language. The project was implemented by Ukrainian Bolsheviks Nikolai Skripnik and Stanislav Kosior.

“We, Great-Russian Communists, must make concessions when there are differences with the Ukrainian Bolshevik Communists concerning the state independence of Ukraine, the forms of its alliance with Russia, and the national question in general,” Lenin wrote back in 1920.

The results came quickly. Ukrainian language classes were introduced in all institutions where educational workers and teachers were trained across the Ukrainian SSR, as well as in schools where teaching was conducted in another language. As a result, the share of industrial workers who increasingly started identifying themselves as Ukrainians grew from 41% to 53% between 1926 and 1932.

However, the ‘Ukrainization’ process was largely imposed from above, forced upon the urban Russian-speaking population, which was mostly dissatisfied with the policies. They were particularly opposed to the requirement to use Ukrainian at formal events and occasions. De-Russification was coupled with propaganda campaigns launched in Soviet newspapers, while publishing in the Ukrainian language was growing rapidly.

This success somewhat tamed the ardor of the Ukrainian Bolsheviks, but the campaign had already picked up steam to the point where it was extremely difficult to stop and the Kremlin was forced to accommodate the local elites’ craving for independence for many more years. It was not until the late 1930s that the Ukrainization project was finally scrapped due to apprehensions that it could revive the Ukrainian nationalist movement. There was also another reason behind that decision – high school graduates often did not speak Russian and, therefore had difficulties at universities where teaching was still conducted in in the tongue.

This apparent imbalance within the educational system spurred the decision to declare national schools ‘hotbeds of bourgeois-nationalist influence on children’.

The ‘Ukrainization’ pursued by the Soviet leadership until the late 1930s laid solid groundwork for the development and growth of the Ukrainian nation and its culture. Even after the project was abandoned, the surge of nationalist feeling it had triggered persisted for many more years by inertia. Soviet policies effectively made the Ukrainian SSR a self-sufficient territorial entity within the Soviet Union, with its own national elite and a class of creative intellectuals, which paved the way for Ukraine’s eventual independence.

The moment of truth

The post-war Ukrainian Soviet Republic went in the opposite direction and began promoting the Russian language and culture. This happened after Nikita Khrushchev hammered scholars and social scientists in August 1946 at the plenary session of the Communist Party of Ukraine’s Central Committee for errors in their interpretations of history.

He challenged them to cultivate “zero tolerance for any manifestation of bourgeois nationalism”among Ukrainian citizens. And the loyalty of Ukrainians to the Soviet regime was ensured by Lazar Kaganovich, a prominent politician in charge of the ‘Ukrainization’ project in the 1920s.

Still, the Ukrainian humanities continued to develop after World War II despite the unremitting party oversight. In 1949, for example, the first volume of the 20-book complete works of poet and writer Ivan Franko was published, followed by Ivan Kotlyarovsky’s collected edition in the early 1950s, and poems by Lesya Ukrainka were prepared for printing. Some research institutes were focusing on Ukrainian studies.

All of that changed after Stalin died in 1953 and his cult of personality was denounced by Nikita Khrushchev, who had been raised in Eastern Ukraine, at the 20th Party Congress. The Ukrainian SSR ushered in a new period of ‘Ukrainization’ after the Khrushchev Thaw had brought partial liberalization. Use of the Ukrainian language saw many changes as well. Dictionaries of the Ukrainian language were compiled and most universities switched to Ukrainian as their language of instruction. Moreover, the Crimean Autonomous SSR, where Russian prevailed, was transferred from the Russian to the Ukrainian Soviet Republic by a decree from Khrushchev.

“The victory in the Great October Socialist Revolution and Lenin’s policy on nationalities allowed the Ukrainian people to create their first nation state,” the first secretary of the Central Committee of Ukraine’s Communist Party, Pyotr Shelest, said in 1970, meaning the Khrushchev Thaw, among other things. And he was right – the national party’s top brass enjoyed a special status in Ukraine, both in the party and government structures.

Notably, this status was reinforced under Leonid Brezhnev, when Vladimir Shcherbitsky assumed the post of the Central Committee’s first secretary. In that period, monuments to Ukrainian Cossacks were erected and an open-air Museum of Folk Architecture and Rural Life in Pirogovo near Kiev was established.

In the stagnation-plagued Brezhnev era, Ukrainians often received top governmental positions in Moscow. It was for a reason that people used to joke, “My golden capital, glorious Dnepropetrovsk,” twisting a line from a popular song about Moscow. In 1965–1977, Nikolai Podgorny, a Ukrainian national, was the chairman of the Presidium of the USSR’s Supreme Soviet and Kharkov-born Nikolai Tikhonov, whose career began in Dnepropetrovsk, was the Chairman of the Council of Ministers from 1980 to 1985. Several members of the Central Committee at the time had ties to the Dnepropetrovsk region. Among them were Andrei Kirilenko, Pyotr Shelest, Vladimir Shcherbitsky, Andrei Grechko, and Dmitry Polyansky.

In the 1980s, when Ukraine’s Communist Party was headed by Shcherbitsky, the Ukrainian SSR was called the last stronghold of communism. But history would have none of it. And a fateful phrase by the president of independent Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk comes to mind in this regard, “Ukraine can be proud to be the state that has shattered the Soviet Union.” Indeed, despite Ukraine being among the USSR’s leading economies and in the top ten most developed European nations, it was the Ukrainian leadership that played a key part in the collapse of the Soviet Union, a multinational country in which the Ukrainian people had held a special position.