How the Nobel Peace Prize Committee has managed to unite Belarusian, Russian, and Ukrainian elites in collective anger

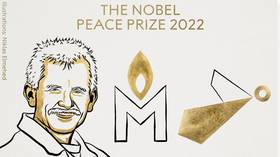

This year, the Nobel Peace Prize has gone to Russia for the fourth time in history and for the second year in a row. But not only that, together with the ‘Memorial’ human rights society, the honor is shared by Belarusian human rights activist Alexander Bialyatsky, and the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties.

The laureates have for many years promoted the right to criticize power and made an outstanding effort to document war crimes and human rights abuses, the Norwegian committee behind the award explained.

What do these people and groups have in common and what does this award mean in the context of the hostilities between Russia and Ukraine?

‘Memorial’: A thread between Nobel laureates from Russia

1987 saw the official beginning of ‘perestroika’. A Russian term which became well known in the West. The authorities of the Soviet Union were actively pursuing reforms, but the consequences were not yet visible. The country wasn’t trembling with separatism in the suburbs, inter-ethnic clashes hadn’t kicked off, and a real economic crisis wasn’t felt. But its citizens were already beginning to taste ‘glasnost’, which saw a relaxation in censorship, détente in international relations, and the flowering of private enterprise.

Across the union, people were banding together to form the political clubs that would become the backbone of Soviet civil society.

From one of these, ‘Memorial’ was born. The young people who founded it set themselves the noble task of rehabilitating the victims of Soviet terror and preserving their memory.

By the autumn of 1988, Memorial had grown into a movement spanning the entire Soviet Union. Its leader was Andrey Sakharov, the first and at the time only Nobel Peace Prize laureate from the USSR. Under his leadership, the society protested and held discussions about the country’s totalitarian past, with a focus on how to make sure the repression never happened again.

What Sakharov failed to do was to get the organization officially registered. Although the authorities themselves were pursuing a policy of rehabilitating victims of political repression, they remained deaf to his requests. Meanwhile, in the regions, administrative pressure was exerted on the members of the society.

The situation was changed by Sakharov’s death in late 1989. At the funeral, President Mikhail Gorbachev asked his widow, Yelena Bonner, what he could do to commemorate the Nobel laureate. “Register Memorial!” Bonner replied instantly. Her request was fulfilled a month and a half later. And Gorbachev received his own Nobel Peace Prize less than a year later.

Notably, Memorial is also associated with the third Nobel Peace Prize laureate from Russia, journalist Dmitry Muratov. He mentioned the organization and its activities in his speech at the award ceremony in Oslo last year. This was not surprising; the Novaya Gazeta newspaper headed by Muratov has been Memorial’s media partner for many years.

From remembrance of repression to human rights advocacy

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Memorial became an international organization engaged in research, advocacy, and education.

For more than 30 years, its members have uncovered archives, published books, compiled databases of victims of repression, and created charitable and educational programs. Thanks to their work, millions of people learned about the fate of their family members repressed by the Soviet regime.

Memorial secured the opening of a monument to victims of repression in Moscow. In 1990, the Solovetsky Stone, named after one of the Gulag camps, was unveiled in the city center next to a statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky, one of the symbols of Soviet state terror. The latter was removed shortly afterwards.

Every year on October 29, on the eve of the Day of Remembrance for Victims of Political Repression, Memorial initiates a commemorative action at the Solovetsky Stone. At this place from 10am to 10pm, the names of people shot during the Soviet terror are read out – first name, last name, age, profession, date of execution. To take part, people stand in line for hours at a time, often in very chilly weather.

Eventually, Memorial went beyond dwelling on the memory of Soviet repression alone. “It simply became impossible to collect profiles of the dead of the repressed and ignore the suffering of the living,” was how members of the society explained their decision to engage in human rights activities. The organization became involved in politics; it supported refugees and opponents of the Russian state, criticized the authorities, and occasionally sued them at the European Court of Human Rights.

Memorial has never received support from the Russian state and has carried out its activities through donations and support from sponsors, including foreign donors. Memorial’s first external donor was the Open Society Foundations of Hungarian billionaire George Soros. Subsequently, the US Agency for International Development, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, various UN departments, and other international entities, as well as the embassies of Britain, France, Germany, and other Western countries joined the list of donors.

It was this foreign money which formed the basis of Memorial’s legal conflict with the Russian state, and which changed its relationship with the authorities. In the first half of the 2010s, it was registered as a ‘foreign agent’. After years of battles over repeated violations of this law, Memorial was finally liquidated by court order in February 2022.

But in addition to the legal conflict between the Russian state and the group, an ideological confrontation has been escalating for years. Human rights activists have taken cases against Moscow to European courts over criminal cases concerning violations of the law on protests.

Also, on numerous occasions, Memorial has drawn attention to alleged political persecution or lawlessness in cases related to terrorism. These have involved not only radical Islamists, but also less straightforward situations. For example, ‘The Network’ case was a high-profile prosecution in the second half of the 2010s; 11 anti-fascists and anarchists from the Russian provinces were accused of forming and participating in a terrorist cell. Memorial took the view that the charges had been fabricated.

Despite Memorials’ joy, the awarding of the Nobel Prize is unlikely to change its status in Russia. Dmitry Novikov, first deputy chairman of the Duma committee on international affairs, said that this would require “either changing the law or breaking it.”

“My prediction is that no such decisions of a provocative anti-Russian nature can in any way induce the State Duma to initiate amendments to the law so that the activities of Memorial are once again legalized and freely carried out on the territory of the Russian Federation,” he explained.

Alexander Bialyatsky: Hoping for a Belarusian Spring

The second winner of this year’s prize, Alexander Bialyatsky, was born in what is now Russia, in Karelia, but has lived most of his life in Belarus – his family moved to Gomel Region when the future human rights activist was only three years old.

Bialyatsky also began his public activities during the perestroika years. As in the case of Memorial, his efforts were initially aimed at restoring the memory of the victims of Stalinist repression. In October 1988, Alexander participated in the ‘Dzjady’ rally, which was dedicated to the commemoration of the victims of Stalinist repressions and was dispersed by the police. He was held administratively liable for his participation.

The protest was organized by the Belarusian People’s Front (BPF), founded by Alexander himself. Its supporters called for “the reorganization of the political system and revival of the Belarusian nation on the principles of democracy and humanism, development of culture, and for the actual state independence of the Republic of Belarus.”

In the 1990s, the party, which adhered to anti-Russian ideas and Belarusian nationalism, would be established on the basis of this movement.

Under pressure from this party, the Belarusian parliament in the 1990s adopted the white-red-white flag, last seen in the Nazi era, and the Pogonia coat of arms as symbols of the state, symbolizing Belarus’ link with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (used by Belarusian collaborators during the Great Patriotic War). There was active de-Russification – for example, despite 87% of the population being Russian-speaking, the Belarusian authorities made fewer than 5% of schools Russian-speaking. The BPF saw the country’s future as aligned with Western Europe and NATO.

Alexander himself was a member of the Minsk City Council in the 1990s and headed the Literary Museum. In 1996, together with his staff, he began helping political activists arrested during protests – this is how the Viasna Human Rights Center appeared, which is still chaired by Bialyatsky.

By the end of the 1990s, he had finally withdrawn from politics and concentrated on human rights activities. However, the country’s authorities did not tolerate his organization’s activities, and in 2003, it was deprived of state registration.

In 2011, Bialyatsky was accused of tax evasion and sentenced to prison. He was released in 2014. Subsequently, he has won numerous awards from the governments of Poland and the US, as well as the European Union.

During mass protests in Belarus in the summer of 2020, Bialyatsky became a member of the Coordinating Council of the Opposition. A year later, he was detained again on charges of not paying taxes. In September this year, a month before he was awarded the Nobel Prize, he was charged again – this time for smuggling a large sum of money.

The activist and his supporters regard all these prosecutions as politically motivated, and designed to stifle his opposition to President Alexander Lukashenko.

Bialyatsky is currently in pre-trial detention. His colleagues from the Viasna Center hope that the award will have an impact on the proceedings. “He is [now] known both in Belarus and internationally. I think this will stand to his advantage and that he may be released,” his colleague, Natalia Satsunkevich, said.

The Center for Civil Liberties: Ukraine’s recipient

The third laureate is distinguished by its ‘youthfulness’: Founded in 2007, the Ukrainian Center for Civil Liberties (CCL) did not emerge from resistance to Soviet dictatorship, nor the perestroika winds of change, nor the chaos of the 1990s.

The organization’s donors include the already mentioned George Soros foundation, the US State Department, the US Congress-sponsored National Endowment for Democracy, the European Commission, the United Nations Development Programme, the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, and other global players.

According to the Nobel Committee, the CCL has worked “to strengthen Ukrainian civil society and put pressure on the authorities to transform Ukraine into a full-fledged democracy.” A somewhat ironic statement at a time when the Kiev regime has effectively become a dictatorship.

The country has moved, in just a decade, from being an imperfect multi-party, democracy – before the Western-backed 2014 Maidan – to a situation where the there is no real legal opposition. At first, the post coup regime banned the Communist Party, who were especially strong in the Russian-speaking south-west, and blocked the Russian press. However, under President Vladimir Zelensky, the move to authoritarianism has accelerated.

Last year, he had the country's opposition leader – Victor Medvedchuk – placed under house arrest. He was subsequently jailed and forced to pose for humiliating photographs before being released in Saudi-negotiated prisoner exchange.

The regime was pushing politically motivated criminal charges on Zelensky's only other realistic rival, former president Pyotr Poroshenko before Moscow launched its military offensive, earlier this year. The president has also banned the state's second most popular party and shut down virtually all media outside his control.

In its early years, the CCL organized all kinds of training and awareness-raising campaigns, but its heyday came in 2013 when mass protests in Kiev eventually escalated into a Western-backed coup d’état.

At the time, the Euromaidan SOS initiative was set up to “assist the protesters and monitor abuses by the security forces.”

Members of the organization actively promoted the idea that the deposed Ukrainian authorities were responsible for the bloodshed during these protests, despite overwhelming evidence that the Maidan snipers incident was the work of the opposition. Subsequently, the CCL even handed over to the International Criminal Court “evidence of crimes against humanity committed by the [President Viktor] Yanukovich regime.”

However, independent research has contradicted this standpoint, pointing out that Western-backed Ukrainian activists have been extremely selective in its consideration of existing evidence, thereby covering up the real perpetrators of the tragedy. The fact Kiev has failed to prosecute anybody for the slaughter also speaks volumes.

In subsequent years, the Center devoted its efforts to participating in monitoring groups in Donbass and Crimea, and campaigning in support of Oleg Sentsov and other activists imprisoned in Russia. In 2017, the CCL established the Kiev School of Human Rights, and in 2020 deployed activists to cover [again Western-backed] anti-government protests in Belarus.

It is noteworthy that over the years, the CCL has not made any statements or investigated human rights violations in Ukraine itself, including the most egregious cases, such as the May 2014 tragedy in Odessa, which left dozens dead.

A new phase of the organization’s activities began after the launch of the Russian military operation in February, a fact also highlighted by the Nobel Committee.

The reasoning of the ruling specifically noted that “following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Centre for Civil Liberties undertook efforts to identify and document Russian war crimes against Ukrainian civilians.” The organization’s main project so far is called ‘Tribunal for Putin’.

Hostile reaction

The fact that this year’s Nobel Peace Prize was awarded simultaneously to representatives of three countries that only three decades ago were considered an indivisible whole is striking to all. Observers have commented that this symbolizes the fact that the liberal wings of the three countries, despite the differences of their governments, remain linked. But many do not like this interpretation.

The most vehement reaction to the news of the Nobel Committee’s decision was in Ukraine.

“[The] Nobel Committee has an interesting understanding of the word ‘peace’ if representatives of two countries that attacked a third one receive the Nobel Prize together. Neither Russian nor Belarusian organizations were able to organize resistance to the war. This year’s Nobel is ‘awesome’,” Mikhail Podoliak, an adviser to President Vladimir Zelensky, wrote on Twitter.

“The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to representatives of Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus. I believe it is unacceptable to accept any prize together with Russians and Belarusians now. This is another justification and an attempt to unite the rapist and the victim. We should reject it,” MP Mariana Bezugla claimed.

“On the one hand, I rejoice at the Nobel Peace Prize for the worthy Ukrainian organization Center for Civil Liberties. On the other hand, association with Belarusians and Russians is inappropriate because it actualizes the Russian myth of ‘three fraternal nations’ which is the basis of the current war against Ukraine,” historian and former chairman of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, Vladimir Viatrovich, wrote on social media.

Igor Kozlovsky, a board member of the CCL, expressed a similar idea: “We react very emotionally and are insulted when Europeans and the Nobel Committee lump Ukrainians, Russians, and Belarusians into one space. We are not against laureates from Russia and Belarus. [But the idea of] ‘Fraternal nations’ offends us.”

However, Moscow is not particularly happy with the Nobel Committee’s decision either. The head of the Russian Human Rights Council, Valery Fadeyev, advised Memorial “to refuse this prize in order to preserve at least some elements of a good reputation.”

He was particularly outraged by the awarding of the prize to the Ukrainian CCL: “Where was this organization in the previous eight years when Donbass was being bombed, when thousands of civilians, children, and elderly people were being killed? They were collecting information about ‘Maidan victims’ – what Maidan victims?! This was a coup instigated and supported by the West. This is not an ideology of defending human rights, it is an ideology of war.”

Leonid Slutsky, the head of the State Duma Committee on International Affairs, pointed out the same thing: “The website of this, so to speak, organization is full of accusations of Russia’s ‘occupation’, articles about the ‘Russian invasion’, and about assistance from the West. And not a single word about the thousands of civilians killed by Ukrainian militants in Donbass.”

The Russian MP concluded that “the Nobel Peace Prize has once again been turned into a political tool.”

“It has once again been awarded to the ‘right’ activists and so-called human rights activists. It is awarded for success in complying with the methodology of the collective West,” he added.