When four formerly Ukrainian regions joined Russia nearly a month ago, the collective West tried to present the occurrence as treacherous, unprecedented, and lacking local support. However, the reunification was preceded by a century-long struggle by a large amount of the regions’ inhabitants for the right to be considered Russians.

In February 2015, the deputies of the parliament of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) signed a memorandum declaring the continuity of their statehood from the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic, one of the numerous entities that emerged during the Russian Civil War. This quasi-state, which was created by the Bolsheviks in 1918 and aspired to become part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), included not only Donbass, but also the Zaporozhye and Kherson Regions.

History may zigzag, but time puts everything in its place. Today, Russian Donbass is restoring lost ties with Russia and establishing new ones,”

wrote Denis Pushilin, the head of the DPR, shortly before the start of Russia’s military offensive.

In this article, RT explores the brief history of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic and explains why the residents of Donbass wanted to live as part of Russia even 100 years ago.

Stretchable borders

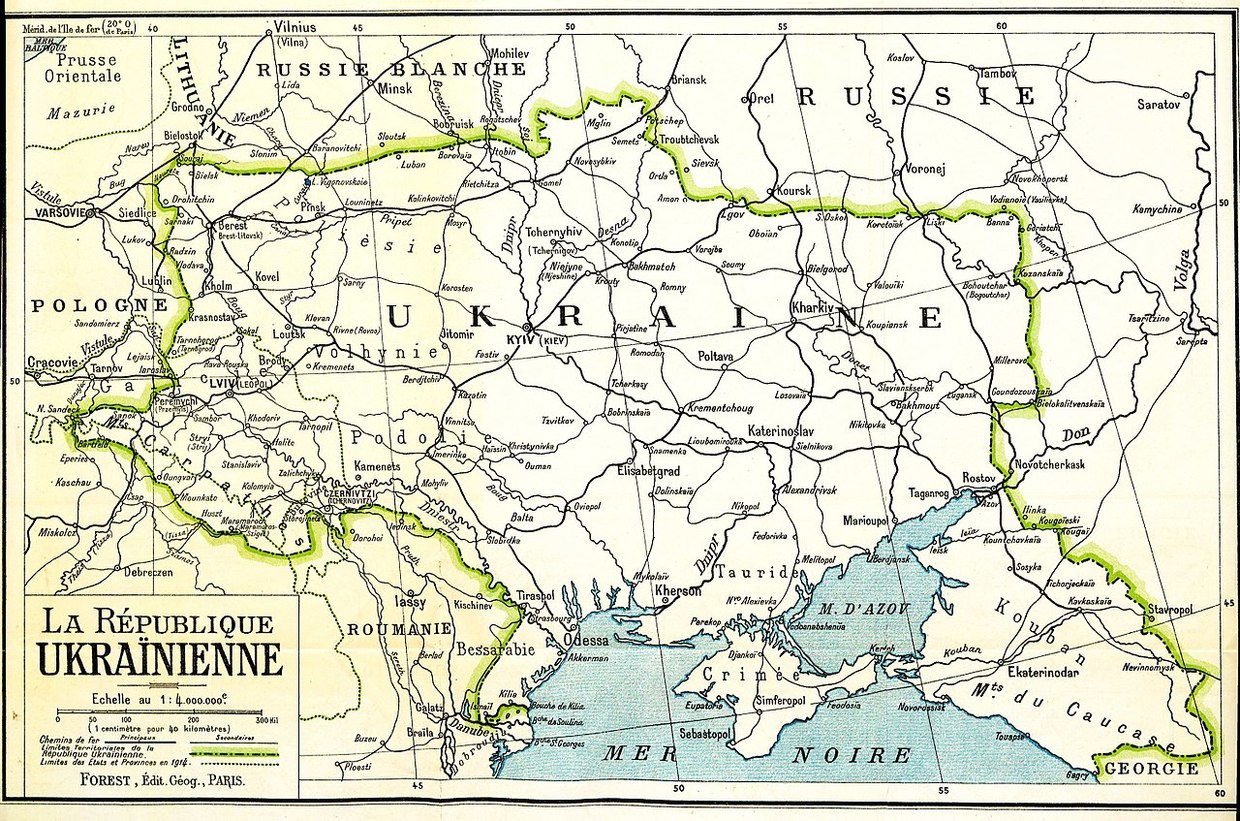

Back in 1999, the famous Russian political geographer and theorist Vladimir Kagansky wrote a large article entitled ‘Ukraine: Geography and Fate of the Country’, in which he made a forecast: Ukraine will inevitably transform, and this transformation mainly depends on Russia. He concluded that its self-determination would inevitably be anti-Russian, citing the country’s “stretchable borders” as one of the main reasons. At a minimum, this would encompass just the right bank of the Dnieper, or even Galicia alone. At a maximum, the borders would stretch to the southern Russian cities of Voronezh and Stavropol.

“The USSR and the CIS are a semi-empire of republics around Russia, and Ukraine is the main link in this necklace, a geopolitical pendant. Ukraine divides the space of the former USSR into separate, geographically separated blocks, and connects three blocks (Belarus and the Baltic States – Moldova – the Caucasus). Ukraine is the only alternative to Russia as the center of the current CIS and the entire post-Soviet space. It is the only way to potentially bypass Russia – the main anti-Russian bastion, and Russia’s main partner in the arrangement of this space,” wrote Kagansky.

In other words, Ukraine is a crossroads of borders, where the main civilizational frontier divides the country roughly in half. This is mainly due to the historical formation of Ukraine. Its entire territory was once part of other, now neighboring countries, as well as independent principalities, and represented the core of individual countries – not only of Kievan Rus, but also the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Moreover, the regions in present-day Ukraine were united for the first time relatively recently – only after the Second World War. At that time, a number of cities and industrial zones were created as parts of a single Soviet space.

When Ukraine finally became fully independent, its authorities faced the task of blending together regions (fragments of the former USSR) that differed in terms of culture, ethnic makeup, and religion. Nevertheless, the Orange Revolution of 2004 and then Euromaidan of 2014 demonstrated that the country remained split into macro-regions. After the ‘Revolution of Dignity’, as it was dubbed by supporters of the overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovich, mass anti-Maidan protests erupted in the Russian-speaking southeastern regions, whose borders demark the historical and cultural territory of Novorossiya. The subsequent attempt of the post-coup authorities to enforce a radical shift in cultural and linguistic policy led to the loss of Crimea and an armed conflict in Donbass, as well as the further marginalization of the Russia-leaning southeastern part of the country.

It was this region that Canadian historian Orest Subtelny singled out back in the 1980s. The results of his ethnolinguistic research on the distribution of native speakers of the Russian and Ukrainian languages in Ukraine showed a stable line that divides the country into two parts with different cultural, linguistic, and, as it turned out, ideological preferences. Russian Ukraine encompasses territories that were never part of the historical Ukraine. These lands include the northern Black Sea region, which was conquered from the Turks and Tatars during the reign of Catherine II; what is known as Sloboda Ukraine, which had been a part of Russia since 1503; Donbass, with part of the territory of the former Province of the Don Cossack Host; and also Crimea.

One of the main macro-regions, which included the former Donetsk, Lugansk, Zaporozhye, and Kherson Regions that recently joined Russia, is made up of the historical territories of Novorossiya. These were annexed to the Russian Empire as a result of the Russo-Turkish wars in the second half of the 18th century. Novorossiysk Province (later called Novorossiysk Region) first appeared as an administrative unit in the 1760s. At various times, it included the Yekaterinoslav, Taurida, Kherson, and Bessarabia Provinces, as well as territories in modern Russia – the Kuban Region, the Black Sea and Stavropol Provinces, and the Province of the Don Cossack Host.

After the October Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks incorporated most of the lands of Novorossiya into the Ukrainian SSR, and the term ‘Novorossiya’ itself was banned. Nevertheless, even among the Bolsheviks, there was serious disagreement as to the territorial arrangement of Soviet Ukraine because some of the regions, most of which became part of Russia in 2022, already gravitated towards the RSFSR.

A problematic region

From April 25 to May 6, 1917, the 1st Congress of Soviets of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog region was held in Kharkov at which the executive committee and system of the region’s district councils were formed. By that time, Donetsk Region had already become the most problematic for Ukraine. Economically, it was connected with the Great Russian core, supplying the latter mainly with coal and other minerals. The population was heavily mixed, with a predominance of former peasants who had come to the area from central Russia to work in the factories. This was also evident in the party’s geographic concentration: of the 51,000 Bolsheviks who lived in what was the territory of modern Ukraine prior to the Maidan Revolution, 31,000 were in the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog basin, and another 5,000 in Crimea.

The fact is that before the revolution, the Donetsk coal basin was located in two administrative regions: Kharkov Province and the Don Cossack Region. After the February Revolution of 1917, the autonomous Central Rada of Ukraine incorporated Kharkov Province into an autonomous Ukraine, proclaiming independence on January 25, 1918.

However, the power of the Central Rada never extended to the territory of Donbass. In December 1917, the creation of the Ukrainian SSR was proclaimed in Kharkov.

At the same time, detachments of Ataman Alexey Kaledin’s Don Cossacks entered the territory of Donbass, including Kharkov Province, but were defeated by the Red Guard in January-February 1918 and left. Meanwhile, the external situation was deteriorating. In Brest-Litovsk (modern Brest in Belarus), the German Empire recognized the Central Rada of Ukraine and signed a peace treaty with it according to which the Germans and Austrians could bring their troops into the territory of Ukraine “to maintain order.” The Austro-German occupation had begun.

According to the Brest Treaty, the Bolsheviks had no right to interfere in events in Ukraine. However, the workers of Donbass were not going to obey the Ukrainian nationalists or Germans. In response, on February 12, 1918, at the 4th Regional Congress of Soviets of Workers’ Deputies of the Donetsk and Krivoy Rog basins held in Kharkov, the Donetsk Republic was proclaimed, and it was emphasized that it was part of Russia. The chief ideologue behind the move, ‘Comrade Artyom’ (Fedor Sergeev), sent a telegram to the head of the Central Executive Committee, Yakov Sverdlov, on the same day, announcing: “The Regional Congress of Soviets has adopted a resolution on the creation of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog basin as part of the All-Russian Federation of Soviets.”

Sverdlov’s answer was brief: “We consider isolation harmful,” by which he meant separating from Soviet Ukraine.

Although initiatives to unite the Donetsk and Krivoy Rog coal basins into one administrative and economic structure existed at the beginning of the 20th century, they were rejected at the government level, as this would have led to an increase in the imbalance between the southern regions of the Russian Empire. However, after the October Revolution of 1917, the autonomist movement in the Donbass began to gain strength, despite the emphatic rejection of this idea by the central authorities. In particular, Vladimir Lenin repeatedly insisted that Ukraine should be united.

Dual government rule

The most intriguing issue here is the territory of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic, the borders of which, as was the case with most short-lived “states” that emerged during the Civil War, were not clearly delineated. However, Comrade Artyom, the main ideologue of the fledgling republic, repeatedly insisted that it encompassed what would be the Donetsk, Lugansk, Dnepropetrovsk, and Zaporozhye Regions of modern-day Ukraine, together with parts of its Kharkov, Sumy, Kherson, and Nikolaev Regions, as well as a part of Russia’s Rostov Region:

“Just a few months ago… the eastern borders of Ukraine were established right along the line which was and still is the western border of our republic. The western borders of the Kharkov and Yekaterinoslav Governorates, including the parts of the Krivoy Rog district and Kherson Governorate which are covered by railways and the districts of the Taurida Governorate above the Isthmus of Perekop have always been and still are the western borders of our republic. The Sea of Azov all the way to Taganrog and the borders of the Soviet coal-mining districts of the Don Region along the railway line connecting Rostov and Voronezh up to Likhaya Station, the western borders of the Voronezh Governorate and the southern borders of the Kursk Governorate complete the borders of our republic.”

Interestingly, Comrade Artyom, a Bolshevik, was citing the agreements reached on July 15, 1917, by Mikhail Tereshchenko, a minister of the Russian Provisional Government, and the Central Rada of Ukraine. Those talks were not coordinated with the central government, the results disappointed both Kiev and Petrograd, and the agreements were never ratified, which means the borders Comrade Artyom was referring to are nothing more than hypothetical. Kharkov, which used to be the capital of Soviet Ukraine, was chosen as the seat of the government of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic.

Another thing to be aware of is that, according to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR) officially discontinued its participation in World War I and was promised military assistance to free its territory from Soviet Russian troops. The Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Republic was thus doomed as it would have been a part of the UPR by default. Yet, no substantial action was taken to eliminate the Soviet Ukrainian republics, five of which were technically in existence at the time (the Ukrainian, Odessa, Don, Donetsk, and Crimean). Soviet Russia signed its own Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers on March 3, effectively confirming the UPR boundaries set in the ‘Ukrainian’ Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

Donetsk–Krivoy Rog was not an independent state and essentially reported to two different governments, that of Soviet Russia (the All-Russian Central Executive Committee) and the Central Executive Committee of Ukraine. However, the need to make swift decisions to combat counterrevolution led the Council of People’s Commissars of Donetsk–Krivoy Rog to establish its own independent General Staff with a mandate to coordinate the patchwork of Red Guard squads active in Donbass (one of those squads was led by a young pipe fitter named Nikita Khrushchev).

Tensions kept rising, which prompted the Donetsk commissars to address workers in early March with the following plea: “The enemy has come very close and is beginning to threaten the Donets Basin. Dispatch all armed units to Kharkov immediately.” On March 8, an emergency meeting was convened in Kharkov to draw up a defense plan, where a mobilization campaign was launched. Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko, the head of Soviet Ukraine at the time, proposed a “military union of the Soviet Republics of the South,” which would bring disparate military forces under unified command.

On March 16, the Council of People’s Commissars of Donetsk–Krivoy Rog issued a “Decree on Military Action,” where it announced the “accession of the republic to the South Russia Military Union for the purposes of jointly fighting German occupation.” Only three days later, on March 19, the Second All-Ukrainian Congress of Soviets in Yekaterinoslav (present-day Dnepr) decided to unite all quasi-states on Ukrainian territory as the Ukrainian People’s Republic of Soviets. This effectively spelt the end of the Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Republic, although documents signed by its Council of People’s Commissars continued to be issued until May.

“A dangerous whim”

Initially, Russia’s central government was in favor of an independent Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic, which it hoped would prevent the Germans and Austrians from advancing into this territory under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which the UPR had signed first. Curiously, just a few days later, Lenin changed tack. In a letter to the then-provisional commissar extraordinary for the Ukraine area Sergo Ordzhonikidze dated February 14, 1918, Lenin wrote:

“Immediate evacuation of grain and metals to the east, the creation of insurgency groups, the establishment of a unified front of defense from Crimea to Great Russia, and a decisive and unconditional restructuring of our forces in Ukraine in the Ukrainian fashion – these are the tasks at hand…

As for the Donetsk Republic, tell our comrades… that, as much as they may contrive to carve their region out of Ukraine, it will still, based on [secretary of internal affairs of the UPR Vladimir] Vinnichenko’s geography, be included in Ukraine, and the Germans will attempt to conquer it. Given that, it would be absolutely ridiculous for the Donetsk Republic to refuse to join a unified front of defense together with the rest of Ukraine.”

According to Lenin’s plan, the high percentage of Bolsheviks in Donbass (60% of their total number in Ukraine) was going to serve as both the catalyst for the fight against the Germans and, later, as the main conduit for Bolshevik policies in the whole of Ukraine.

Ultimately, the plenary session of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) held on March 15, 1918, decided to “consider the Donets Basin as a part of Ukraine.” That, however, did not save Donbass from being occupied by the Germans in April–May 1918.

The Red Army recaptured Donbass in the winter of 1918–1919, but the Soviet leadership did not reinstate the Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Republic, instead keeping the region within Soviet Ukraine as the key proletarian counterweight to the largely peasant Ukrainian population.

They did not stop at the part of Donbass formerly belonging to the Kharkov Governorate and endowed the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic with a region in the south that they took from the Province of the Don Cossack Host. By 1920, Soviet Ukraine contained the whole of Donbass and the port of Taganrog on the Sea of Azov. That redrawing of borders could not be explained by ethnic motives. Even though the majority of people living around Taganrog were Little Russians (Ukrainians), the Donbass proletariat was mostly of Great Russian origin and represented a balanced cross section of Russia’s general population.

The only reason for giving Donbass to Ukraine was its status as a major industrial powerhouse in the south of Russia. Had it remained in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic would have been an almost exclusively agrarian region without a sizeable proletarian population. At that time, the Bolsheviks were skeptical about peasants, especially well-to-do ones, as most Ukrainian farmers had been prior to the revolution. Lumping Donbass together with Ukraine was an attempt to have a loyal class in the nascent republic.

In 1925, a small part of Donbass with the towns of Shakhty and Kamensk, as well as Taganrog were given back to the RSFSR and the current Russian-Ukrainian border was established. However, most of Donbass, including the major cities of Yuzovka (Donetsk) and Lugansk, remained in the Ukrainian SSR so that it could have at least some industrial production of its own. Eventually, the Bolsheviks merged the coal-mining regions of Donbass first into the Donetsk Governorate and then into the Stalino Region, which later split into the Donetsk and Lugansk Regions.