Operation Uranus: The day Hitler’s Nazis were smashed and the Soviet Union began to take the upper hand in WW2

On February 2, Russia celebrates the Day of Military Honor. Exactly 80 years ago on this day, the Red Army won the bloodiest fight in human history – the Battle of Stalingrad. The victory of the USSR was brought about by the successful counter-offensive operation ‘Uranus’.

This feature was first published on November 20, 2022, the 80th anniversary of the beginning of that counter-offensive.

Early in the morning, exactly 80 years ago, the soldiers of the 3rd Romanian Army were awakened in their cold dugouts on the right bank of the Don River by the roar of artillery hitting their positions. By lunchtime, Commander Petre Dumitrescu reported to the leadership of Army Group South that it was impossible to prevent the enemy from crossing the river. A day later, his group was shredded by massive tank strikes. Two weeks later, it practically ceased to exist.

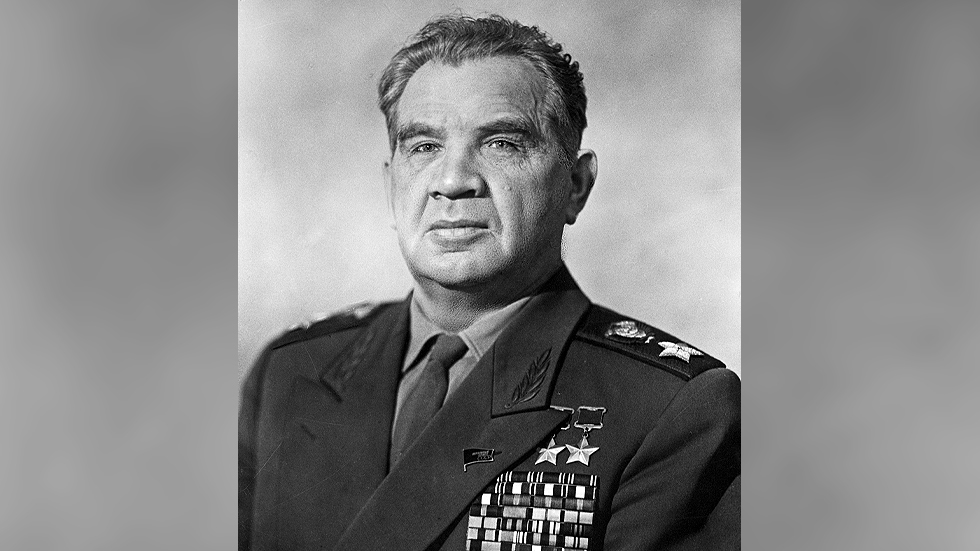

At that point, the Soviet troops of the Southwestern Front under the command of Nikolai Vatutin began their part of Operation Uranus, which resulted in the first major strategic defeat for the Axis countries – the beginning of the end. For the Allies, the Battle of Stalingrad would long stand as a symbol of military fortitude and Russian military genius.

What were the key mistakes of the German command? What revolutionary warfare methods did the Soviet generals employ during the Battle of Stalingrad? What non-obvious consequences did the disruption of the German offensive in southern Russia have?

A decisive November

The autumn of 1942 is considered the turning point in World War II. The seemingly relentless offensive of the Axis powers and their seizure of new territories and resources were finally put to an end in all theaters. By December, the strategic advantage had swung to the Allies. After this, only they would dictate the course of the war, and the Germans and the Japanese could only react.

Of course, the British would claim that the tide was turned in Egypt near El Alamein on October 24, when Bernard Montgomery managed to beat the Desert Fox Erwin Rommel and his African Corps, who were exhausted by a shortage of supplies. This put an end to German attempts to invade Egypt and block the Suez Canal, which would have significantly complicated the situation for England, since the island nation was extremely dependent on food and resources supplied by its colonies. Two weeks later, the British in North Africa were already supported by the Americans in the West, who were conducting Operation Torch – a large-scale troop landing in Morocco and Algeria, which were formally under the control of France’s pro-Hitler Vichy government. Despite Rommel’s stubborn resistance in Tunisia, the outcome of the campaign was a foregone conclusion.

However, the Americans themselves tend to believe that the outcome of the war in the fall of 1942 was decided not in North Africa, but on the opposite side of the world – on the island of Guadalcanal in the Pacific. The landmass was of great strategic importance, as control over it made it possible to secure commercial shipping between Australia and the United States and threaten the large Japanese naval base in Rabaul (New Britain). In August, US Marine Corps units landed on the island and immediately captured an important airbase, later called Henderson Field. Throughout the autumn, the Marines successfully defended this site with the support of aviation and the navy. The decisive battle was on November 13-14, when the Japanese lost their entire landing force, which was supposed to support the garrison of Guadalcanal, as well as several large ships, including the battleships Hiei and Kirishima. Japan’s expansion to the south was checked at the Solomon Islands and New Guinea, and it only lost previously captured territories after December of 1942.

But, in point of fact, neither Hitler nor Stalin had any doubts that the future of the world was being determined on the Volga steppes from November 19 to 24, when 270,000 Wehrmacht troops under the command of Friedrich Paulus were forced into a cauldron by a heavy blow from the Southwestern and Stalingrad fronts. The subsequent failure to unblock the encircled units doomed the Blau plan and killed any hopes Berlin had for a successful outcome to the war.

Blue is the color of (Hitler’s) sadness

The German General Staff called the plan of action on the eastern front ‘Fall Blau’, or Blue. The main goal of the campaign in the summer of 1942 was initially to capture the oil fields of Maikop and Grozny. The fuel reserves stored in Germany before the war were coming to an end, and synthetic fuel and Romanian oil from Ploiesti were not enough to service all of the Wehrmacht’s tanks and Luftwaffe’s planes. Therefore, the offensive in the Caucasus was considered a priority. Stalingrad was a secondary goal, and storming the city was not envisaged. It would be enough to pummel it with constant artillery fire, as was the case with Leningrad. However, at first things went so well for the Germans that capturing the industrial and transport center on the Volga began to look like an easy and even natural task. This deceptively low-hanging fruit eventually buried the Third Reich.

The Red Army’s failures in the spring and summer were primarily due to Stalin’s and the Soviet High Command’s mistakes in assessing the enemy’s plans. The fact is that the invasion of the USSR was initially dictated by the need to seize the resources of Ukraine and the North Caucasus. It was the seizure of the Lebensraum im Osten – the living space in the East – that Hitler and Rosenberg first thought about when authorizing the Barbarossa plan. This was also anticipated by Stalin, who concentrated his main forces in the west of Ukraine in 1941. Due to the suddenness of the attack and catastrophic errors in management, these troops were destroyed in the Battle of the Border and later near Odessa and Kiev.

But the German generals, led by Chief of General Staff Franz Halder and Paulus – the main drafter of the Barbarossa plan (such is the historical irony) – were able to convince the Fuhrer of the need to repeat the blitzkrieg that brought victory in France. They considered it possible to destroy or trap the main part of the Soviet army in cauldrons with tank spearheads, after which they could take the enemy’s capital and force a surrender. However, the stubborn resistance of the Red Army near Smolensk and Moscow proved that such calculations were a mistake, even if not yet fatal.

In the 1942 campaign, Stalin was sure his adversary would try to finish what he had begun and take Moscow. Therefore, the main forces of the Red Army were concentrated in the central part of the country. But this time Hitler had no choice – he had to urgently ensure the safety of the Kuban agricultural fields and the mines of Donbass, get Grozny oil, and prepare an offensive on the Baku and Azerbaijani oil fields.

The Red Army forces’ weak position in the south deteriorated further after an incompetent attempt by Semyon Timoshenko’s troops to retake Kharkov in May. As a result of a counteroffensive conducted by the 6th Paulus Army and 1st Panzer Group Kleist, 240,000 Soviet soldiers and officers were captured in the Barvenkov cauldron alone. The front actually collapsed, and what official reports called a strategic retreat was, in practice, more like an escape.

It was at this moment that Hitler, inspired by this success, decided to divide Army Group South into two parts. The first was sent to the south to fulfill the main mission of capturing the oil fields, which by that time had already been set on fire by Soviet oilmen, with a subsequent strike on Rostov-on-Don. The second – consisting of the 6th Paulus Army, the 4th Goth Tank Army, and two armies made up of Romanians, Hungarians, and Italians – was to pursue the Soviet units retreating to the east with the aim of besieging Stalingrad and capturing Astrakhan by winter.

While controlling Astrakhan would have completely cut central Russia off from Caucasian oil, Hitler saw the attack on Stalingrad more as a personal blow to the enemy’s leader, as the city bore his name. It was here in 1918 that Stalin found his most loyal political ally, Voroshilov, as well as his main enemy, Trotsky. It was also here that American engineers had built one of the symbols of Stalin’s industrialization policy, representing the industrial power of the USSR – a colossal tractor plant.

The resistance to the main onslaught, which was organized by the 62nd and 64th Armies on the distant approaches to the city, was weak and clearly ineffective in steppe conditions. It seemed to the German command that the Russians were about to finally run out of strength, and the last defenders of the city would die in its ruins amidst the smoke and fires from incessant bombing.

How wrong they were.

Father of modern warfare

Lieutenant General Vasily Chuikov was recalled to Stalingrad from China, where he had served as a military attaché and chief military advisor to Chiang Kai-shek since December 1940. He had thus missed the initial stage of the Great Patriotic War, although he had been asking to be sent to the frontlines ever since the fighting started. It may just be that not having the weight of the bitter defeats of the first year of the war on his shoulders gave Chuikov the moral fortitude to keep defending Stalingrad till the end.

What made him famous though was his personal courage, doggedness, strictness bordering on rudeness, and even a certain daredevil attitude. Back in July 1942, his plane was shot down by a German fighter while he was inspecting his defense positions. Three months later, on October 14, as the city was being stormed for the third time, even his nerves of steel were beginning to rattle as the army headquarters was hit with a projectile. Chuikov suffered a blast injury, dozens of army staff members died. And yet he remained firmly committed to his motto:

There is no land for us behind the Volga.

What did Stalingrad look like in September-October 1942? It was a narrow strip, hardly more than 1km wide, of densely built residential and industrial areas that had been devastated by bombing and shelling. Buried in the rubble were the corpses of several thousand civilians – and soldiers from both sides. The air was foul with the stench of burning factories: Red October, Barrikady, the brick plant, and, of course, the giant Stalingrad Tractor Plant. Oil was burning and seeping from storage tanks into the Volga, as barges and boats carried reinforcements from the left bank to the right and wounded soldiers from the right bank to the left at night under relentless enemy aircraft fire.

By mid-November, the Soviet 62nd Army’s line of defense had been split into several islands. It is difficult to give exact numbers because fighting continued nonstop, but experts say there were no more than 20,000 Soviet troops along the actual line of contact and about three times as many German soldiers from General Paulus’ Sixth Army (with the total size of the German group estimated at about 270,000).

A lot of the action was almost hand-to-hand combat. Trapped by rubble and barricades, German tanks couldn’t maneuver and became an easy target for antitank guns and Molotov cocktails. Frontlines would run across staircases in apartment buildings, with Soviets often mounting counteroffensives at night approaching from basements, attics, or sewer pipes. Snipers attracted a lot of attention, with Soviet propaganda extolling Vasily Zaitsev as a hero. His legendary, albeit not entirely corroborated by historical evidence, duel with the chief instructor of a German sniper school was the inspiration for ‘Enemy at the Gates’, a Hollywood movie, where Zaitsev, a simple lad from the Urals region of Russia, is played by Jude Law. According to veterans’ reports, however, it was not the sniper rifle that decided the outcome of the Battle of Stalingrad but the simple PPSh submachine-gun, with its very high rate of fire and close combat effectiveness.

Before Stalingrad, there had been virtually no historical precedent of fighting in big, built-up cities, except perhaps the siege of Madrid by General Franco’s forces. There were no manuals or guidelines describing urban fighting. Chuikov and his soldiers wrote those rules with blood on the destroyed walls of buildings. The general and his army, later renamed the 8th Guards Army, drew on that experience later during the Battle for Berlin, which fell within a week.

Since then, cities rather than fields and woods have increasingly seen the fiercest fighting, from Warsaw, Konigsberg, and Seoul to Grozny, Fallujah, and Mariupol. Modern warfare was born in Stalingrad.

Ghost of an executed marshal

Temperatures fell sharply to 18-20 degrees Celsius below zero at night in early November. As the German Sixth Army, worn out by a months-long offensive, freezing, decimated by bloody urban fighting, and suffering from inconsistent supplies along the few steppe roads, which autumn rains had turned into mud, was persevering in its attempts to carry out Hitler’s orders and push Chuikov’s army into the river, its fate was decided hundreds of kilometers away from Stalingrad at the flanks of the overextended front that were protected by poorly equipped and under-motivated Romanian armies. It was there that the main strikes of Operation Uranus were delivered on November 19 and 20.

Uranus was the first in a series of brilliant Red Army operations, which already bore many of the hallmarks that came to define the strategy of the Soviet General Staff.

First was the highly unpredictable choice of the main strike areas, as the attacks were not aimed at the flanks of the Sixth Army itself but rather at areas deep behind it. Second, maximum secrecy was adhered to during the preparation period to conceal the true intentions from the enemy. The perceived hopelessness of the resistance on the part of the defenders of Stalingrad lulled Hitler into assuming, until the very last, that the Red Army was fighting at the top of its capabilities and had no resources for a counteroffensive.

Third, unorthodox solutions were found to complex problems and ample supplies were provided to the attacking forces. A case in point is the airborne mission to supply antifreeze to the mechanized units of the 51st and 57th Armies that were being deployed in the steppes south of Stalingrad. The cold snap was forcing armor crews to dig pits under their tanks, cover them with tarps for protection and keep fires burning under them to prevent water coolant from freezing and destroying the engines. In the absence of a proper road system, it was impossible to deliver enough antifreeze within the short period of time left before the launch of the offensive. Eventually, over 60 tons of antifreeze coolant was brought from the Moscow region by air using cargo gliders. In the course of a week, pilots completed about 60 resupply missions, flying in a semi-reclined position inside plywood contraptions in freezing cold, often at night.

Finally, Uranus was the first major operation executed in accordance with the deep operations theory developed by Vladimir Triandafillov in the 1920s. The theory, which emphasizes destroying enemy forces not only at the line of contact but throughout the depth of the battlefield, was refined and introduced into the Red Army manual by Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky. After Stalin’s purges of the military in 1937 and Tukhachevsky’s execution, the theory was declared wrong and even harmful. Yet it was borne out by practice and was crucial for the success of the Battle of Stalingrad. The same approach was used with the Battle of Kursk, the Battle of the Dnieper, Operation Bagration, the Vistula-Oder offensive, and many others.

Close call for the allies

Traditionally, the main outcomes of the Battle of Stalingrad are said to be the frustration of Germany’s offensive plans, Moscow retaining control over oil supplies from Baku along the Volga, the Wehrmacht’s large-scale retreat, the protection of the Caucasus from further German advances, the fact that the Red Army now had the strategic initiative, and a major boost to the Soviet troops’ morale after such a decisive victory culminating in the capture of a German field marshal. The foreign-policy dimension is also frequently discussed, as it paved the way, in the winter of 1943, for the first negotiations between the Allies about the post-war spheres of influence, which eventually led to the Tehran Conference.

However, there is one important consideration that is usually ignored because it goes way beyond one theater and has to do with the bigger picture of the war. What if, instead of getting bogged down in Stalingrad, Hitler had continued with his initial plan of capturing the Caucasus? What if he and his high command had been more realistic in assessing their capabilities? What if the Germans had succeeded in crushing Chuikov’s 62nd Army after all?

Just before the Second Battle of El Alamein, Erwin Rommel had to leave his army and return to Europe to treat his diphtheria. As he was preparing to hand over command to his subordinate, Rommel wrote a detailed memo for the Fuhrer describing the situation at hand and asking him to advance into the Caucasus as soon as possible. If the German troops had not been immobilized in Stalingrad in the summer of 1942 and had instead moved into Transcaucasia, Britain would have been forced to transfer its troops from Africa to northern Iran. Pro-German sentiment was strong in Iraq, while Syria and Lebanon were controlled by the collaborationist French Vichy regime. Turkey, which remained neutral until almost the very end of the war, had strong economic ties to Germany.

After the defeat in World War I stripped Berlin of its colonies, the revival of the country’s economy was mainly due to new markets in the Balkans and Turkey. Surrounded by the Germans on all sides, Ankara would likely have joined the Axis, especially given the prevalence of nationalist and revanchist sentiment in the country, as well as the age-long dream of seizing control over southern Azerbaijan from Iran. This development would have changed the situation globally, creating a new theater and threatening British oil production in Iran. Ultimately, it would have improved Germany’s chances of winning the war, or at least protracting it by a year or two.

In any case, November 1942 would certainly not be seen as the turning point of World War II today.