‘There is no God here’: How conflict between the Orthodox Christian Church and the Soviet Union helped define modern Russia

“Madmen, come to your senses, stop your bloody massacres. What you are doing is not only cruel – it’s a satanic deed, for which you’ll burn in the fires of hell in the life to come, and will be damned by posterity.” With these words, the Head of the Russian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Tikhon, addressed the people in February 1918. The speech was a response to anti-religious pogroms happening all over the country.

It marked the beginning of a long conflict between the Soviet government and the Orthodox Church, which reverberates in Russian society to this day. A religious believer who also sincerely supports Communist ideals and feels nostalgic about the USSR is a seemingly contradictory and exotic type of person, but rather common in Russia. A famous example being the politician Gennady Zyuganov, who believes Jesus Christ himself was a Communist.

An “Earthly paradise” without the clergy and churches

The revolution’s main ideologists demonstrated open contempt toward religion. Many people are familiar with Karl Marx’s phrase, “Religion is the opium of the people”. Vladimir Lenin didn’t care to choose his words either when he said, "Every religious idea, every idea of God, every ‘flirtation’ with God is the most unspeakable, dangerous abomination, and a vile infection.”

The persecution of the Christian Church began immediately after the revolution when the Bolsheviks came to power. A month hadn’t passed when Archpriest Ioann Kochurov became the first priest to be killed and the seizure of churches and monasteries also began. On February 1 (January 19, according to the calendar in use at the time), armed revolutionaries attempted to seize the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, killing the priest Petr Skipetrov and arresting Metropolitan Veniamin and the Superior General of the Lavra, Bishop Prokopiy.

In response to these actions, Patriarch Tikhon issued a statement calling the revolutionaries “madmen”, “monsters” and “Satanists”. The Patriarch excommunicated the Bolsheviks from the church, forbidding them to take communion.

Tikhon's reaction was expected, but the worst was still to come. The oppression of religion was sealed on a state level. The first such act was the "Decree on the Separation of the Church and State”, signed into effect the very next day after the patriarch's statement.

The act legally deprived the church of all privileges, and the country became secular. Today, such a law hardly seems surprising, but at the time, it was a severe blow for Russia. The majority of the population was Orthodox, for almost two centuries the church had been part of the state and was governed by a state institution – the Synod, marriages were registered in Orthodox churches, and many priests received a state pension. The new decree declared all church property as belonging to the people, and in fact, the property was seized in favor of the atheist state. However, all this was just the tip of the iceberg.

The Red Terror and the Church

A year after he anathematized the Bolsheviks, Patriarch Tikhon delivered an inflammatory message to the Council of People's Commissars, in which he accused the Soviet government of bloodshed and deception.

In general, however, he kept a restrained position and spoke in favor of the church as an apolitical structure. He called Christians to prayer and repentance: “Resist them with the power of your faith, with your powerful nationwide cry, which will stop the madmen and show them that they have no right to call themselves advocates of the national good.”

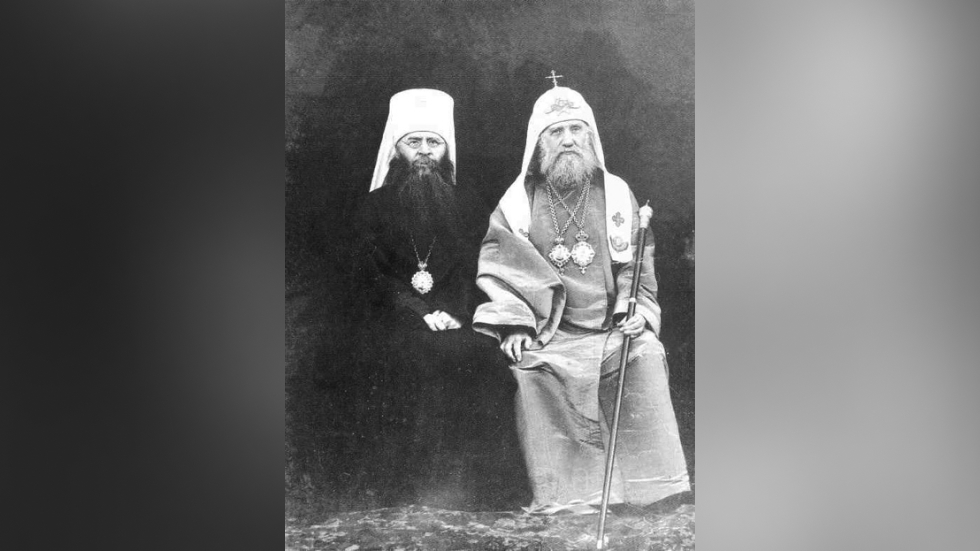

The Patriarch was repeatedly placed under house arrest – first in 1918, then in 1919, and finally in 1922. The state security agencies tried to beat him into admitting anti-state activities, but Tikhon had nothing to confess. Nevertheless, in 1923, he signed the famous “penitential” statement addressed to the Supreme Court of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), famous for the words: “... from now on I am not an enemy of the Soviet government.”. Advocating peace and seeking to preserve the church did not help the Patriarch – he was often arrested, placed under investigation, and survived several assassination attempts.

Tikhon died in a hospital on March 25, 1925. State security agents gave the Patriarch no rest until his final breath. His life was a constant search for compromise, as is evident from words quoted by his contemporaries, “May my name perish in history, if only it would benefit the Church”.

However, neither the Patriarch's reconciliatory position nor his sacrificial death stopped the persecution of believers. The revolutionary slogan: “Long live the red terror!” shook the Orthodox Church. Beginning in the winter of 1918, while the Patriarch was still alive, revolutionaries shot religious processions in Voronezh, Lutsk, and Kharkov. From 1918 to 1923, 28 bishops, thousands of priests, and over ten thousand believers were killed. From February to May 1918, 687 people were killed in attempts to protect church property.

The violence was driven by two factors. First, the church and believers were declared “counter-revolutionaries”, enemies of Bolshevism, and supporters of the revival of the monarchy. Secondly, murders and robberies were committed by ideological Bolsheviks driven by propaganda or professing communist ideals.

If you can’t destroy it, adapt it to your needs

Yet there were still many more believers than committed communists in Russia. So in order to quickly divert people away from the faith, the Bolsheviks chose another means– they created a new church, loyal to the state.

Some priests, led by Alexander Vvedenskiy, recognized the Soviet government and were given permission to build a parallel religious organization – the “Living Church” or the Church of the Renovationists. They even obtained an audience with the Chairman of the Central Executive Committee and prominent Soviet politician Mikhail Kalinin, which led to the establishment of the Supreme Church Administration.

“Living Church” members supported the Soviet state, recognizing it as legitimate and fair. The number of parishes in this organization gradually grew, and traditional Orthodox parishes were handed over to them. In 1925, 9093 parishes (one-third of all parishes in the country) belonged to the organization. But the need for the fictitious organization was short-lived, the USSR remained an atheistic state, and by the end of World War II, the “Living Church” ceased to exist.

Patriarch Sergius played an important role in the history of this organization. Many believers still accuse him of creating a state-controlled Orthodox church. Sergius was the Metropolitan of Vladimir at the time of the October Revolution. In 1921 he was arrested and sent to Butyrskaya prison, but was soon released and exiled to Nizhny Novgorod, where he made his first historical decision. Together with two other metropolitans, he recognized the church of the Renovationists as “the only legitimate one”. This was a serious crime against the Orthodox canonical church, even if Sergius did not recognize many of the Renovationists’ reforms.

In 1922, Sergius changed his mind. He completely renounced the church of the Renovationists, and publicly repented in 1923.

After the death of Patriarch Tikhon, the Russian Orthodox Church remained without a leader. The Patriarch's place was taken by his deputy – the Patriarchal Locum Tenens, a position soon filled by Metropolitan Sergius. In 1926, he was arrested by state security agents and accused of ties with emigrants, but six months later Sergius again became Locum Tenens of the Russian Orthodox Church and penned an important decree, the “Declaration of Metropolitan Sergius”.

In it, Sergius condemned the clergy who emigrated, called them “our foreign enemies” and stated that the church did not oppose the Soviet state. This was the first major recognition of Soviet power by the Orthodox Church and remains controversial among believers.

The fateful year of 1937

In the 1930s, despite the timid beginnings of a dialogue between the church and authorities, the persecutions did not stop. Over these years, the Orthodox church was significantly weakened, the number of parishes and priests greatly decreased, and a Soviet citizen could receive a Christian education only in secret. Anti-religious propaganda had intensified through the means of literature, press, cinema, and education. The Soviet citizen was brought up to disdain Christianity, and by 1931, over 5 million people were members of the “Union of Militant Atheists”. The Church had suffered a catastrophic blow, but most Russian people still stuck to their faith.

In 1937, a census was held in the USSR. Its results both surprised and dismayed Soviet Union leaders. 56.7% of Soviet citizens still considered themselves believers despite the risks and wide-scale propaganda. Theresults triggered a new wave of repression.

In 1937-1938, the Bolshevik Politburo approved a plan which established quotas for execution. The priests and clergy fell under the category of “anti-Soviet elements”.

From August to November 1937, 31,359 “churchmen and sectarians” were arrested, among them were 166 metropolitans and bishops, 9,116 priests, and 19,904 believers. A total of 13,671 people were sentenced to death, including 81 bishops, 4,629 priests, and 7004 ordinary parishioners.

In the Russian Empire, there were 78 thousand Orthodox churches. By the beginning of the Second World War, the number had already decreased to the hundreds – according to various estimates, from 120 to 400 parishes. The number of priests decreased at least 20 times, to 5,700.

Eventually, the war halted the persecution of the church.

The war and the Church's right to exist

After Nazi Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union, the Church and the Soviet government joined forces to fight the invader. Patriarch Sergius addressed the people on the first day of the war, 12 days earlier than Stalin, stating:

It is not the first time that the Russian people must endure trials. With God's help, we will turn the fascist enemy to dust.”

The church organized prayer services and collected money to help the army. Believers collected over 8 million rubles to create a tank column in honor of Dmitry Donskoy, the great Russian saint. In total, the Church was able to collect more than 200 million rubles for the needs of the front during the war.

In 1943, Joseph Stalin met with three metropolitans of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Kremlin. The Patriarchate was officially restored in the USSR. For the first time after Patriarch Tikhon, a new church leader was appointed – Patriarch Sergius. The authorities legalized the Synod and bishop councils, opened many churches and monasteries, and released some priests from camps and exile.

Russian holy warrior Alexander Nevsky became an important part of Soviet wartime propaganda. His images were printed on posters and a movie was made about him. An aerial procession was also held with the icon of the Mother of God placed inside an airplane and flown over the Kremlin and Moscow.

New persecutions

After the victory in the war, Stalin continued the peaceful policy regarding the church, and even wanted to hold an Ecumenical Council and declare Moscow the center of world Orthodoxy.

However, the Council did not take place as Stalin's interest in the church quickly faded. From 1948 until the death of the “leader of the peoples”, Orthodox churches remained closed, and repressions resumed. In 1948, 3,296 people were arrested for religious activities, and that number doubled to over 6,000 in both 1949 and 1950. The persecutions were not as brutal or wide scale as in 1937, but they had again shaken the barely recovering church.

After Stalin's death, the Orthodox Church finally had a chance to break away from the scrutiny of the state. Many church communities were registered by the authorities and did not face persecution. However, this did not last long.

The next Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, began oppressing the church once again. His set of anti-religious measures became known as the “Khrushchev church reform”. Although believers were no longer shot and tortured, as in the 1920s, the new policy focused on imprisonment and church closures. Khrushchev’s own words say a lot about the goals of the reform. In 1961, he declared,

I promise you that we will soon show the last existing priest on TV!”

The reforms started at the end of the 1950s, when a major “purge” occurred in the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church. The chairman was suspended, and the Council was filled with communist party members actively engaged in implementing the state’s “new” policy.

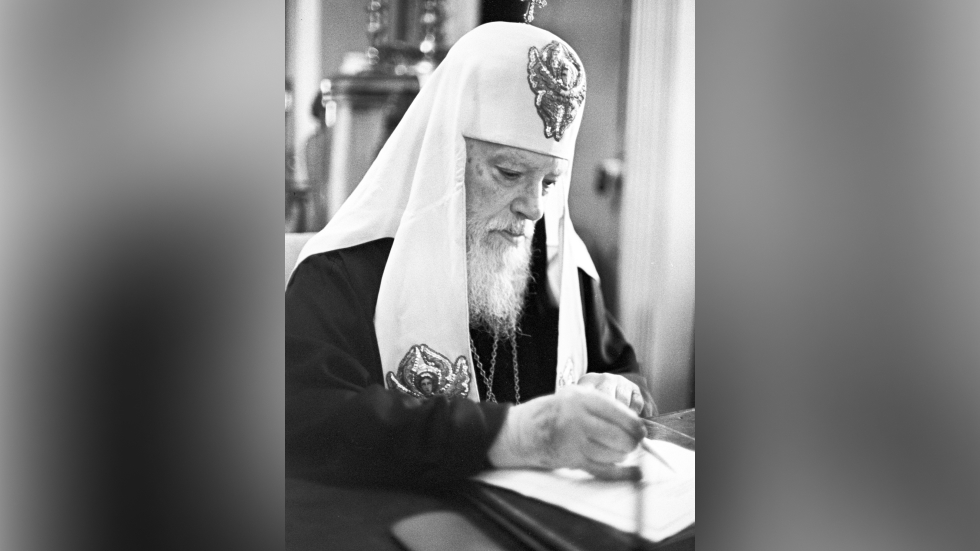

After meeting the new members of the Council in early 1958, Sergius' successor, Patriarch Alexy I, said: “It will likely be difficult for the new comrades to work with the Church, since they were active in anti-religious activities.”

In 1961 under pressure from the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church, the Holy Synod adopted a resolution that prohibited all priests from handling economic affairs in parishes. Instead, they were managed by people from the church council, who weren’t even believers. Archbishop Nikon recalled the results of the reform: “The clergy became subordinate to the elders, who often acted of their own accord <...> The clergy were not allowed to attend the meeting where the church council was elected. An atheist could decide the fate of the church community, but a priest had no right to do so...”

The Soviet government put all state measures into effect to oppress the church: monasteries, convents, churches, and theological seminaries were closed. Of the eight seminaries operating in 1947, only three remained open after the Khrushchev campaign. The authorities refused to register new parishes and closed existing ones. The main cathedrals in Novgorod, Orel, Riga, and Chisinau were shut and historic churches in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Krasnoyarsk were destroyed.

The fight against the church was accompanied by active anti-religious propaganda. The press regularly published articles criticizing the church, propaganda circulation increased, and believers were officially labeled “obscurantists” and “fanatics”.

Khrushchev also tried to use the space program to bolster his anti-Church drive. He famously invoked Yury Gagarin in a 1961 speech saying the cosmonaut "flew into space, but didn't see any god there". Ironically, Gagarin himself was said to be a believer, who kept icons in his home.

The most prominent space-faring atheist was Gherman Titov, whose flight followed Yuri Gagarin’s by four months. In 1962, he told an American audience that he had seen no Gods or angels in space. This poster – which states ‘There Is No God!’ commemorates him.

The Church after Khrushchev

Khrushchev was forced to resign in 1964, and the last of the most difficult times for the church finally came to a close. For the USSR, the next 20 years went down in history as the “era of stagnation”. Soviet citizens no longer believed in a “bright atheistic future”.

However, the number of parishes was still declining, albeit at a slower pace. Any public demonstration of religion was forbidden, baptisms and church weddings were performed in secret, and people could be fired for simply attending church.

There were also cases of criminal prosecution. For example, math teacher B. Talantov died in jail following his imprisonment for collecting signatures against the closure of a church in the Kirov region. A former student of the Institute of Cinematography was sentenced to five years in exile for anti-Soviet propaganda after he was caught conducting religious and philosophical seminars and distributing Christian literature.

However, there was also some progress. In 1981, the publishing department of the Moscow Patriarchate moved from a small monastic premises to a specially constructed building. The Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate showed that the number of reports of ordinations increased significantly after 1978. This meant it was becoming easier to enter the priesthood. Dissident religious circles also sprang up at this time and charismatic preachers appeared, such as the well-known missionary Alexander Men.

The final years of the Soviet Union

The church gained ground in the final years of the Soviet Union after Mikhail Gorbachev came to power and launched “perestroika”. The move towards a democratic society required improved legislation and a respect for the rights and freedoms of citizens, including the right to profess religion and freedom of speech.

However, the Church only began to benefit from democratization in 1987, when Orthodoxy was finally able to come out of the shadows and resume educational and spiritual activities. Parishes began to be registered and the distribution of religious literature was no longer a criminal offense. In that year, the State announced an amnesty for convicted dissidents and priests imprisoned or exiled for religious activities.

1988 marked a historical date: the 1,000th anniversary of the Baptism of Rus. On this occasion, surrounded by reporters, Mikhail Gorbachev met with Patriarch Pimen in the Kremlin. Gorbachev called the Baptism of Rus “a significant milestone in the centuries-old formation of national history, culture, and Russian statehood.”

This moment may be considered the full stop in the long-standing conflict between the Orthodox Church and the Soviet state. In just a couple of years, the USSR would disappear for good, leaving Russia to deal with left-over “militant” atheists and a church ready for compromise with the authorities.