The insanity of war: Is this avoidable conflict driving Ukraine out of its mind?

In a recent post on X, Aleksey Arestovich – the former consigliere of Ukrainian President Vladimir Zelensky and now his sworn enemy (and would-be rival, too) – has addressed his “dear countrymen” to tell them that Ukraine appears “collectively insane.” A ruthless spin master and, at times at least, intelligence asset, Arestovich also claims to be a psychologist. In that capacity, he had even more – and worse – to announce: Not only is Ukraine a case of nationwide “pure progressive lunacy,” but also of “individual” madness. It is a fair guess that this was a specific reference to his former master Zelensky and his team.

Clearly, Arestovich has chosen his words for maximum effect. But he also added plausible examples of striking absurdity in Ukraine’s politics and public sphere. These included the back-and-forth over the removal of the military’s top general Valery Zaluzhny; bizarre statements by men with power and guns that those not quick enough to submit to cannon-fodder hunters should be “shot in the knee” (making Ukraine’s army, as one commentator aptly noted, the first one you can get invalided into instead of out of); and a general spirit of “Let them all croak, as long as we get national unity.”

And to add insult to injury, the former Zelensky collaborator comes to a damning conclusion: The test of war, he decreed from the safety of exile, has shown that Ukraine is “extraordinarily psychologically weak” because, he asserts, “a massive” share of Ukrainians of all ages and kinds has rapidly entered a “zone of anomality.”

That spreading “psychosis,” Arestovich claims, is payback for “building your house on sand,” on illusions instead of a realistic assessment of Ukraine’s place in the world and its capacities. What Ukrainians have fought for will now crush them, he darkly concludes.

So far, so harsh. (And wrong as well, on at least two important counts, but we’ll get to that.)

Arestovich may or may not play an important role in future Ukrainian politics; he obviously wants to. But let’s not focus on him. It’s more fruitful to acknowledge that he has raised a valid question, even if his answers are flawed. What are the psychological effects of the war on Ukrainian society?

It is easy to guess that they must be profound and pervasive by now. Notwithstanding the years of low-intensity conflict starting in 2014, if the large-scale war that began in February 2022 had ended quickly, this would not be the case. But since the West and the Zelensky regime decided to waste the peace opportunity of spring 2022 and instead continue the proxy war on behalf of the US, Ukrainian society has now been affected deeply and widely.

Military casualty numbers are not published, but we know that they run in the hundreds of thousands. Civilian casualty rates, fortunately, approach nothing comparable to the genocidal massacre inflicted by Israel on the Palestinians in Gaza. Russia has clearly not pursued a strategy of targeting civilians but focused on genuine military targets or infrastructure (such as power grids) that is dual-use, as does the US, routinely and, if anything, more thoroughly. Yet, over time, the total of civilian losses has accumulated. According to the UN’s OHCHR, since February 2022, 10,382 civilians have been killed, and 19,659 injured.

Displacement and economic hardship have been much more common. As of late 2023, the UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) counted 6.3 million Ukrainians displaced abroad and almost 3.7 million internally. Some 4.6 million have, as of now, returned from temporarily leaving the country. Of course, different kinds of being affected by the war interact. As The Lancet pointed out as early as spring 2022, the “cumulative effects of war and displacement since 2014 are likely to predispose many Ukrainian people to adverse mental health outcomes.”

Regarding Ukraine’s economy, suffice to say that 14.6 million of those Ukrainians in Ukraine will be in need of humanitarian assistance in 2024, as the UN estimates.

Clearly, Arestovich’s cynical comment that Ukraine’s society has proven “weak” is not only offensive but factually wrong. Instead, it has been resilient under pressure – by no means as severe as that suffered by Palestinians in Gaza but substantial, nonetheless. That the Zelensky regime has abused this resilience for an unpatriotic (to put it mildly), misguided, and lost cause is a different matter to which we will return.

But their resilience does not mean that Ukrainians have not suffered great psychological stress. Some effects of the war are exactly what you would expect. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) – in essence, a persistent condition of ramifying shock – is mostly (but not exclusively) associated with military veterans and their families, plus those of the fallen. According to a quasi-official Ukrainian estimate, this group alone – with an especially increased likelihood of lasting stress disorders – will end up including between 4 million and 5 million Ukrainians. While it is impossible to predict how many of them will actually develop clinical conditions, historical experience points to around 20%. Yet keep in mind that that will still be the (large) tip of the iceberg, because those suffering less acutely will still be suffering. Their lives as well will have been changed.

Regarding the population as a whole, even for summer and fall 2022, a study based on standardized questionnaires and published in the Cambridge University Press journal Psychological Medicine found substantial increases in anxiety, depression, and loneliness. By the spring of 2023 – that is, even before the catastrophic failure of the Zelensky regime’s wasteful summer offensive – a Ukrainian poll-based study found consistently worsening mental health among Ukrainians. A Ukrainian psychologist commented that their psychological resources had been used up. That is almost a year and much bad news ago.

Research also published last year in the International Journal of Mental Health Systems has come to even more dramatic conclusions, stating that “the war has had devastating effects on the health and well-being of the Ukrainian nation, and has led to a rapid escalation of a mental health crisis,” while the mental health care system, not strong to begin with, has been weakened further.

It is certain that the problems sketched above have only become worse. Yet they are also not specific to Ukraine. This kind of trauma is what modern war does to society, any society.

There is a more complicated issue, though, which many Ukrainians and their Western “friends” (friends from hell who will use you for their proxy wars, that is) are loathe to face, but it is there nevertheless. The question is not only how much damage the war has done to the minds and souls of Ukrainians, but also in how far the Zelensky regime and its intellectual collaborators and media surrogates are responsible for making their mental lives even more miserable. And behind that question there is another one: Is the Zelensky regime itself sane or insane?

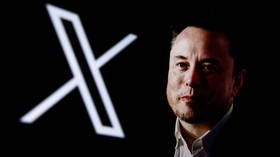

It is in this regard that Arestovich’s X post displays some real insight, perhaps because he used to be part of that regime and, in his day, did his level best to help make his countrymen delusional with nationalist propaganda, while criminally downplaying the risks inherent in war.

His most important point is that illusions – deliberately cultivated – are at the core of Zelensky’s regime and, I would add, personality. That “house built on sand” is a toxic fabrication of three main components. First, Zelensky’s own delusions of grandeur, his “Churchill complex,” which was fed by the West in a way similar to how Bill Clinton used to ply Boris Yeltsin with drinks.

Secondly, as I have argued before, there is a larger ideological-psychological complex of national messianism, cultivated by Ukrainian elites (with the help of Western war enthusiasts like the publicist Tim Snyder). In this delusion, Ukraine is imagined as a fore-post of the West. That West, in that construction, is, of course, not the real, proxy war-waging, genocide-complicit one, but yet another delusional, self-flattering fantasy of “liberal” values, democracy, and, last but not least, moral superiority.

And not only is Ukraine accorded the “honor” of serving as its bulwark, but also as a sort of youth elixir, a place where a West still wonderful but sometimes tired, can steel itself again. In reality, this complex is toxic for Ukraine, part of those things that Arestovich has aptly described as fought for by Ukraine only to crush it now.

Thirdly, there is a pathological voluntarism in Ukraine’s elites, again exacerbated by their Western friends – a long unquestioned belief that everything Ukraine and its sponsors want hard enough will happen. Instances of this form of madness include the repeated hyping of miracle weapons, such as Western tanks, planes, and missiles, or, indeed, NATO doctrine. This magical thinking is supplemented by a bizarre tendency even among Western experts with (some) reputation left to lose to build strategic castles in the air, such as in recent attempts to “re-imagine” Ukraine’s desperate military situation as a viable base for successful attritional warfare. Freudian Reality Principle? Not so much.

In all his arrogance, Arestovich has a point. But not about Ukraine as a whole. Ukraine is not “weak.” Rather, its tragedy is that its considerable resilience and strength have been abused and betrayed by a regime that has sold the country to Western, in particular US, interests. To do this, that regime has done its best to drive Ukrainians into a delusional state. To an extent it has succeeded, but that will pass. The ultimate irony, however, is that that same regime, its domestic elites, and its Western “friends” have also drunk plenty of their own Kool-Aid. They, unlike most Ukrainians, are unlikely to ever recover. Even after defeat.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.