‘I’m afraid of dying’: How and why Ukrainian men hide from military service

Ukraine’s general mobilization – announced in the spring of 2022 – changed the lives of thousands of military-age men. There are questions about the motivation levels of forced conscripts, yet Kiev desperately needs more troops in the combat zone. In an attempt to escape tightening mobilization laws, Ukrainian men are resorting to increasingly desperate measures: from donning strap-on breasts to risking their lives by crossing the border. Here, we look at the steps the Kiev authorities are taking to hunt down draft dodgers, and the risks many are willing to take to avoid being caught.

Tightening what looks more and more like a noose

After the start of Russia’s military operation in February 2022, the Ukrainian authorities imposed martial law. General mobilization followed soon afterwards. The rights of a significant part of Ukraine’s male population have been restricted ever since, including a ban on military-age men from leaving the country. However, in April of this year, the rules were further tightened, and the draft age was lowered from 27 to 25.

Moreover, a category describing people as having “limited fitness” for military service was abolished. A potential serviceman is now either “fit” or “unfit” for duty. This effectively means that the Ukrainian army is conscripting people who would be considered unfit for service in most parts of the world – such as those with HIV, chronic viral hepatitis, stage 1 hypertension, and even those with hearing problems and “neurotic mild mental disorders.”

All Ukrainian men between the ages of 18 and 60, regardless of whether they are fit for duty or exempt, must now carry a military ID. Without it, men cannot receive a passport to travel abroad. Kiev has even refused to provide consular services to Ukrainian men living outside the country. Foreign Affairs Minister Dmitry Kuleba said that men of military age who are “sitting abroad” will not receive consular services from a nation that they don’t want to defend.

All Ukrainian men must personally register at a military office. Violators face penalties ranging from 17,000 to 22,500 hryvnia ($415-$550) – which is around the same as the average monthly salary – to the confiscation of driver’s licenses. Military enlistment offices can also contact the police, who will deliver a conscript by force.

Persons exempt from mobilization include police officers, employees of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau, the State Bureau of Investigation, the Prosecutor’s Office, the State Emergency Service, MPs, ministers, judges, employees, and the owners of defense-industry enterprises.

Other exemption categories include disabled persons, fathers of many children, single parents, those with disabled children, and students.

Included in the amendments to the mobilization law is the removal of a paragraph concerning the demobilization of military personnel who have already served for 36 months.

Ukraine is resorting to such measures because it desperately needs more people in the army. This is an issue often discussed among oits leadership. Kiev believes that increased mobilization will deliver a breakthrough on the battlefield. When announcing the new measures, Vladimir Zelensky explained that the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) and its former commander-in-chief, Valery Zaluzhny, had insisted on 450,000-500,000 more recruits.

The process has picked up speed. Defense Ministry spokesperson Dmitry Lazutkin told the NV.ua outlet that the situation has significantly changed since the end of the winter of 2023 and early spring of 2024. He claims that 4.6 million men eligible for military service have updated their information. “This shows us that there is an [information] base that we can work with,” he explained.

Lazutkin did not, however, disclose the specifics. He claims that Ukrainians’ attitude to military service has changed. According to the spokesman, in previous years the decision to join the army was more emotional. “Now, the nature of such decisions has changed. People weigh [the decision], consciously look for a unit, a brigade, a position [that fits them] and in this way determine their fate,” he said.

Since the start of mobilization, media reports have shown the lengths to which conscription officers are willing to go to deliver military summonses. As countless videos demonstrate, a man can receive a notice virtually anywhere – on the street, at a gas station, market, in a café, or at the gym.

The Ukrainian government has allowed Territorial Recruitment Centers (TRCs), the official term for military enlistment offices, to deliver summonses regardless of where a man’s military registration is. This means a summons can be served at a his place of residence, work or study, in public places, buildings, crowded areas, and at checkpoints and border crossings. Summonses can be distributed not only by military commissars but also by special “notification groups” that include those who are not subject to mobilization, local officials, the management of enterprises, and public institutions.

Crowds of draft dodgers

The Ukrainian authorities try to lure men to the front, but they do their best to hide. According to an ex-lieutenant colonel of Ukraine’s security service (SBU), Vasily Prozorov, the number of draft dodgers who have illegally left the country has significantly increased since the new law on mobilization was adopted. He says people have realized that the situation both at the front and in Ukraine is getting worse.

“The results (of the new mobilization law – RT) are best summed up by footage from the streets of Ukrainian cities. It clearly shows that things are going very, very badly with mobilization,” Prozorov told RIA Novosti, commenting on a video in which TRC employees are seen attempting to catch people on the streets.

Last fall, even TRC representative Yury Semchuk, as quoted by UNIAN, claimed that 99% of Ukrainian men are dodging the draft. According to Semchuk, the elite has fled and only “genetic slaves” remain in Ukraine. As an example, he told the story of a volunteer who went to the front to escape problems with his wife. Ukrainian society is being depleted and there are people who are ready to “be under anyone’s [rule],” Semchuk stated.

In April, Politico estimated that over 650,000 men of fighting age have fled Ukraine since the start of the conflict with Russia.

“The early burst of patriotic fervor which saw draft centers swamped with volunteers has evaporated. An estimated 650,000 men of fighting age have fled their country, most by smuggling themselves across the border,” the publication stated.

According to one Politico correspondent, about a third of the passengers on a train carrying him out of Ukraine were men of military age.

Ukrainian Minister of Internal Affairs Igor Klimenko has also acknowledged that officials are aware of hundreds of thousands of possible draft dodgers.

Service in the armed forces has become less popular even among prisoners, according to Roman Kostenko, secretary of the Ukrainian parliament’s (Verkhovna Rada) Committee on National Security, Defense, and Intelligence, as quoted by Ukrainskaya Pravda. Kostenko attributes this to most of the motivated having already joined the AFU. In his opinion, Ukraine will be able to mobilize about 5,000 prisoners.

The country “needs to make it possible to mobilize people who are currently in pre-trial detention. This will allow us to attract more people into the army,” he said. Kostenko confirmed that 3,800 prisoners are already serving in the AFU, most of whom have recently completed their training and some of whom have already been wounded.

The prevalence of draft-dodging varies across different Ukrainian regions. As NV wrote in mid-July, most refuseniks since the start of 2023 were from Ukraine’s western regions. In Lviv Region, the TRC issued 85,800 notices for draft evasion. Transcarpathia (54,200 notices), Ivano-Frankovsk (33,000), Ternopil (28,700), and Khmelnitsky (20,500) regions were also among the areas with the greatest number of those falling to report for duty.

However, in Kiev just 11,400 search notices were issued during the same period, while there were 2,500 in Kharkov Region. In 2022, the greatest number of complaints (15,800) about criminal offenses committed by men eligible for military service was also filed in Lviv Region.

Masks and Telegram to the rescue

Mobilization raids have led to a game of ‘hide and seek’ between men of military age and recruitment centers. To avoid recruiters, many Ukrainian men do not leave their homes, rely on food delivery services, and carry emergency alert devices in case they are caught by conscription officers, according to the New York Times.

Aleksandr, a 36-year-old IT manager, told The Guardian that he rarely goes outside, avoids public transport, and travels only in his car. He moved to an expensive area of Kiev because usually TRCs hunt for men in poor neighborhoods. He also claimed that some of the apartment owners in his building are MPs. “The military don’t visit here. Our compound is an island of survival. To be poor in Ukraine is to be dead,” Aleksandr’s wife, Nastya, told the newspaper.

Nastya added that she is so worried about her husband of 12 years that she has begun to suffer panic attacks. “We are one organism. If he dies, I will die too. Maybe I will kill myself,” she said. The couple have supported their country and the army, and even bought a prosthesis for a soldier who lost his leg, but they believe it’s time for Ukraine to negotiate with Russia.

Ukrainians have also come together to help each other escape the draft. Special Telegram channels have been created where users can report where they have spotted conscription officers, so that others can avoid them. Posts on these channels are usually coded. For example, conscription officers are known as “clouds” or “rain.” A typical post might look like this: “What’s the weather like at the Defenders of Ukraine metro station?” Reply: “Three clouds covered a young guy.”

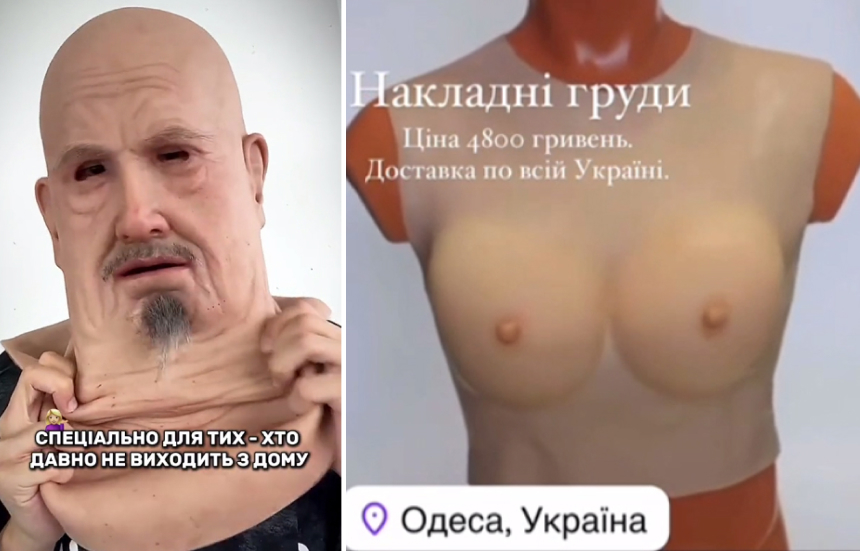

Various Ukrainian websites and online marketplaces have started selling old man masks and strap-on breasts. With some items costing over 10,000 hryvnia (just short of $250), such “life hacks” are supposed to help men avoid being caught by draft officers.

Fleeing across the border

Many Ukrainians choose to flee abroad to escape mobilization. This, however, can be no easy feat, and many men rely on difficult and sometimes dangerous routes to get out of the country. The Guardian tells the story of Miroslav, who left Ukraine on foot in October 2023. He took only a small backpack with him and walked for a day through fields and forests until he reached Hungary. At some point, he noticed border patrol officers and lay hiding in the grass for 40 minutes. Finally, he climbed through a hole in the border fence and went to a Hungarian police station. He is currently in Warsaw. “I didn’t want to fight. I’m afraid to die,” he said.

One of several escape routes used by draft dodgers is the Tisa River, which separates Ukraine and Romania. In April, the Romanian authorities claimed that since the beginning of the war, over 6,000 men have crossed the river, while 22 have died in the attempt.

This route is perilous. The fact that thousands of Ukrainians would rather risk their lives by crossing the river than joining the AFU underscores Kiev’s problems, the NYT noted.

As Sergey Lebedev, coordinator of the Nikolaev underground, told RIA Novosti, Ukrainians have come up with a new escape route via the Moldova transit zone of the Odessa-Reni highway. Cars are not allowed to stop in the area, so people leave them on the highway and run towards the Moldovan village of Palanca. Some even buy cheap vehicles to escape, which the authorities then recover. Abandoned trucks have also been spotted along the road.

Greasing palms

The pervasive unwillingness to be enlisted has led to large-scale corruption in Ukraine: a bribe to escape mobilization ranges from $10,000 to $17,000, underground activists from various regions told RIA Novosti. The price depends on the number of intermediaries involved in the corruption scheme, the region, and the distance to the state border. Escaping from Kiev or its surroundings is most expensive.

For the kind of fees mentioned above, a person can be removed from the conscription database if he’s registered at a military enlistment office. If a person isn’t registered, help in crossing the border costs about $10,000.

However, there are no guarantees that having paid for his freedom once, a person will avoid being caught by draft officers or security forces and conscripted later.

According to Lebedev, in Nikolaev Region the average bribe to avoid conscription is $12,000.

All across Ukraine, bribes to escape military duty have soared since general mobilization in 2022. In previous years, prices ranged from $2,000 to $3,000, and until the recent tightening of mobilization laws, the price had remained stable at around $5,000.

And given recent developments in Ukraine, the price will most likely go way up.