Pushkin turns 225: Why is he Russia’s most celebrated poet?

This year, Russia celebrated the 225th birthday of the great poet and writer Alexander Pushkin. The importance of Pushkin and the extent of his influence on Russian culture can hardly be overestimated. In 1859, literary critic Apollon Grigoryev famously said, “Pushkin is our everything,” and in Russia, this principle has remained unshakeable for two centuries. While in the mid-19th century, Grigoriev’s contemporaries may not have unanimously agreed with him, today virtually no one can refute this.

We will explore why Pushkin is so important and why he is a key figure in Russian culture.

Alexander Pushkin was born on June 6, 1799. He came from a noble family and was brought up according to the standards of high society. Pushkin’s years of study at the Tsarskoye Selo Imperial Lyceum in 1811-1817 were an important milestone in his education as a poet. At that time, Pushkin's talent first became known – his teachers and friends recognized his gift, and this largely determined his future.

Pushkin lived only 37 years but left behind a huge literary and cultural legacy – scholars, philologists, and philosophers study it to this day. He died on February 10, 1837 in St. Petersburg after being mortally wounded in a duel with the French military officer Georges d’Anthès.

During his short life, Pushkin wrote 14 poems, six plays, 12 novels and short stories in prose, seven fairy tales, a vast number of poems, and his immortal novel in verse, Eugene Onegin.

The modern Russian school curriculum includes over 40 works by Pushkin (including short poems). Children first become familiar with his works in 5th grade literature class. No other Russian writer has such a prominent place in the country’s education system.

We speak the language of Pushkin

What makes Pushkin such an important figure? Russia has produced many outstanding writers. The entire world knows Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Chekhov. Compared to them, Pushkin is less well-known on a global scale. Moreover, we can’t say that Pushkin surpassed other great Russian writers in terms of language proficiency, or the sophistication and importance of the issues raised in his works.

However, one important aspect sets Pushkin apart from all other Russian writers. Russian literature is a huge cultural layer that reflects the history, social life, and public sentiments of this vast country over a period of 200 years. The key to understanding Pushkin’s legacy is precisely this 200-year timeframe. Pushkin was the ‘founding father’ of Russian literature, and helped it develop into an international cultural phenomenon.

Of course, there were many writers before him – the works of Lomonosov, Karamzin, Radishchev, and Fonvizin are studied in all Russian schools. Many chronicles, poems, and songs had likewise been written during the course of country’s 1,000-year history. However, Russian literature as we know it, and which is studied not only in Russia but all over the world, started with Pushkin.

It is often said that: “Alexander Pushkin created the modern Russian language,” and “In Russia, we all speak the language of Pushkin.” Of course, these statements cannot be taken literally – over 200 years, like in any other language, Russian has undergone significant changes. New words have appeared, the alphabet has slightly changed, and there have been some changes in punctuation and syntax. Many studies conducted over the past 30 years show that modern Russian is quite different from the Russian of that time – the vocabulary, phrases, and linguistic constructions have changed.

However, the roots of modern Russian can be found in the works of Pushkin. We clearly see this when reading his works; today, they are published in their original form. Literature written prior to the beginning of the 19th century is more difficult to understand; modern Russian has a lot more in common with the language of Pushkin than the Russian that was in use at the time of his birth.

In just 20 years, Pushkin managed to introduce, popularize, and even standardize Russian in the form that we know and speak today. Pushkin’s linguistic innovations are unique, and modern Russian speakers rely heavily on them without even being aware of it.

Prior to Pushkin, Mikhail Lomonosov’s ‘theory of three styles’ – high, medium, and low – was predominant in Russian literature. The names of these styles already point to their differences. The high style was based on Church Slavonic, and had nothing in common with the language spoken by the people. The low style had no elements of high style and was a mix of everyday expressions with an informal vocabulary. However, some elements of high style appeared in colloquial language, mainly among the upper classes.

Philologists and language scholars agree that such divisions significantly hindered the development of the Russian literary language, and many late-18th century writers felt that they were constrained by this theory. As a result, literary works dating back to the 1790s often differ greatly – some of them are quite easy to read, while others are very difficult for modern readers.

Pushkin accomplished a great task– he rejected the idea of division into styles and introduced the vernacular into his works. Pushkin did not want to limit himself when it came to the natural riches of the language. The ease of his language, the liberty he took with the order of words, and the accessibility of his writing all contributed to the fact that Russian writers gradually adopted his innovative ideas.

A renowned linguist and specialist in Russian and general semantics wrote, “Grammar-wise, Pushkin’s language is in many ways closer to the modern [Russian] language than that of Pushkin’s contemporaries and even later authors.” Indeed, many of the phrases and words that we find in Pushkin’s texts today are so familiar to modern Russian speakers that they cannot appreciate the extent of the poet’s innovations. For Russians, it is simply their familiar native language.

At the same time, we must remember that Pushkin had perfect command of the Russian language. A writer cannot simply write in a ‘folk’ dialect, he needs to weave everyday language into the literary language, while preserving its beauty and richness. Pushkin was unparalleled in this.

In his ‘Letter to the publisher’, Pushkin wrote, “A skilled writer profits from the richness of the language, its expressions and phrases. The written language is enlivened by expressions born in the middle of a conversation, but it should not renounce all that which it has acquired over the centuries. One who writes only in colloquial language does not know the language.”

Pushkin did not hesitate to borrow words from foreign languages (mainly from French), and as a result, Russian absorbed many foreign words. He introduced many French words – including ‘раlеtоt’ (coat), ‘bottine’ (shoe), ‘bureau’ (office), ‘voile’ (veil), ‘regisseur’ (director), ‘gelée’ (jello), ‘marmelade’ (marmalade), and ‘pistolet’ (pistol). These are just a few examples; Russian has many more. Presently, we are talking only about 19th-century vocabulary, since with the development of technology, Russian has also absorbed many Anglicisms which have become part of the everyday language.

However, even though he freely borrowed words from foreign languages, Pushkin was no Westernizer. He understood that foreign words must be used with care, otherwise instead of being enriched, the language may deteriorate.

Even though Pushkin did not create the modern Russian language, in terms of the general rules, linguistic constructions, phrases, and traditions, Russian people indeed speak the language of Pushkin.

Pushkin in politics and beyond

When speaking of Pushkin, we cannot merely laud his linguistic contributions. Pushkin wrote many works, and in them we find a reflection of his views, ideas, and beliefs.

Like many outstanding writers, Pushkin didn’t shut himself away from public and political life. Since he was quite emotional and did not restrain himself, he openly expressed his views on critical issues in many works. He strongly reacted to what was happening around him and spoke out on many things that bothered him, often on the spur of the moment.

Because of this, it is quite difficult for someone who is not familiar with Pushkin’s body of work to understand the poet’s views: He could condemn Russian Emperor Nicholas I in one poem, and sharply rebuke foreigners in another.

Pushkin openly advocated the abolition of serfdom and harshly criticized law enforcement structures. He supported the Decembrist uprising of 1825 and deeply empathized with the Decembrists. In 1818, he wrote a poem ‘To Chaadaev’, which ends with the following lines:

Dear friend, have faith: the wakeful skies

Presage a dawn of wonder – Russia

Shall from her age-old sleep arise,

And despotism impatient crushing,

Upon its ruins our names incise!

Scholars have not agreed upon one conclusion regarding these lines. Some believe that Pushkin advocated the fall of the monarchy and the establishment of a new political system; others say he only opposed despotism and tyranny, but did not reject the emperor and monarchism as such. The latter seems more plausible, since the poet himself was selflessly devoted to Russia and believed that the highest goal of every Russian is to serve their country.

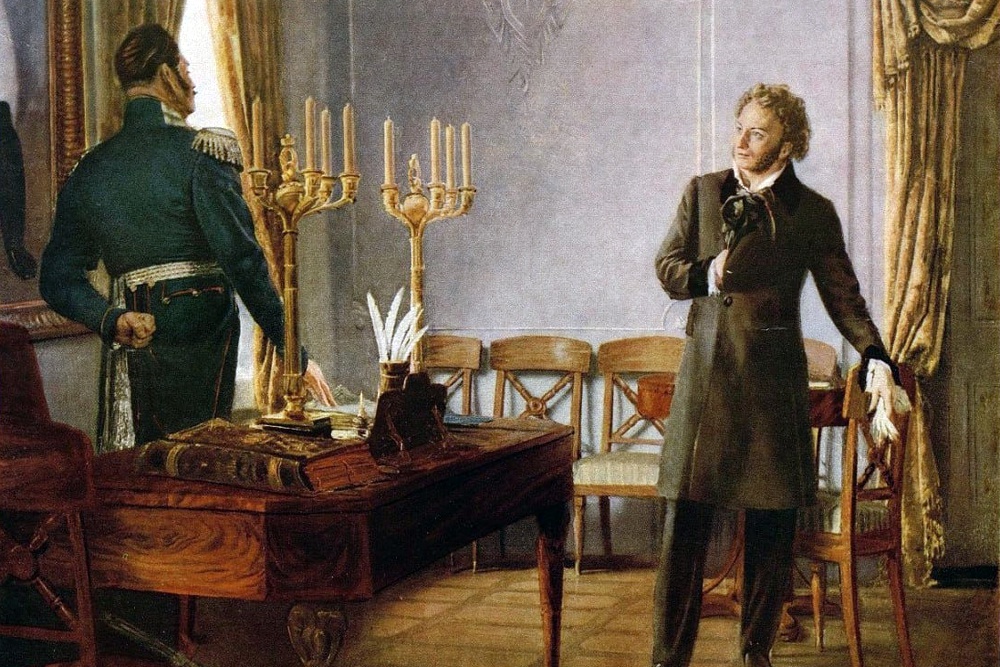

Nevertheless, Pushkin’s refusal to accept many aspects of Russia’s domestic policy played an unfortunate role in his life. He was sent into exile by two different emperors – Alexander I and Nicholas I – for criticizing their policy at different times. After Nicholas I ascended the throne in 1825, Pushkin was kept under the watch of the secret police, and sometimes wasn’t allowed to leave the country.

In fact, due to his outspoken behavior, Pushkin had a ‘supervisor’, Count Alexander von Benckendorff – the chief of the Separate Corps of Gendarmes and the head of the Third Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery (i.e. the secret police) – with whom he exchanged letters. Pushkin and Benckendorff regularly corresponded, and it was Benckendorff who banned Pushkin from traveling abroad in 1829. However, two years later, Benckendorff allowed the poet to return to government service after Pushkin requested access to libraries in order to write about Peter the Great.

Pushkin’s relationship with the authorities was quite paradoxical – on the one hand, they disliked the poet for his overly liberal views, but on the other hand, they knew that he was a true patriot and a genius, and did not want to censor him. It was easier to endure his (often insulting) criticism, than for Russia to lose someone like Pushkin.

Pushkin’s poem ‘To the Slanderers of Russia’, is quite different. It was written in 1831, during the uprising in Poland (which was then part of the Russian Empire). At the time, France called for a military intervention in support of Poland. The initiators of this campaign were mainly pro-militarist politicians. The poem contains these verses:

What moves your idle rage? Is ‘t Poland’s fallen pride?

‘T is but Slavonic kin among themselves contending,

An ancient household strife, oft judged but still unending,

A question which, be sure, ye never can decide.

In fact, ‘To the Slanderers of Russia’ is quite relevant today. In the poem, Pushkin clearly states that the conflict is an internal one and is deeply rooted in the past. Other countries cannot understand it, so foreign statements indeed resemble slander against Russia. Pushkin also believed that the intervention of Western military forces would not resolve the conflict, which was incomprehensible for the West.

The scale of Pushkin’s personality is so immense that his works were always available in Russia and were not censored during any period of Russian history. The emperors disliked him but did not prevent the publishing of his works; after the abolition of serfdom in 1861, Pushkin came to be regarded almost as a prophet in Russia; and even Soviet censorship, known to be very harsh, did not ban Pushkin – 50 years ago, his works were studied in schools as scrupulously as they are today.

In the collective consciousness, Pushkin will always remain the ‘sun of Russian poetry’, and a ‘great people’s writer’, because indeed, “Pushkin is our everything.”