The harrowing story of Beslan, part one: What led to the worst terrorist attack in Russian history?

Russia has a long and painful history of terrorism. From political assassinations in the 19th century to lone-wolf attacks in the 1980s, it has encountered all manners of horror. However, the most brutal attacks were carried out in the late 1990s and early 2000s by Islamist militants. The Beslan school siege in September 2004 stands out as the worst terrorist outrage in Russian history.

RT presents a three-part story about a tragedy that continues to shock Russians even 20 years later.

Politics, Separatism, War and Jihad

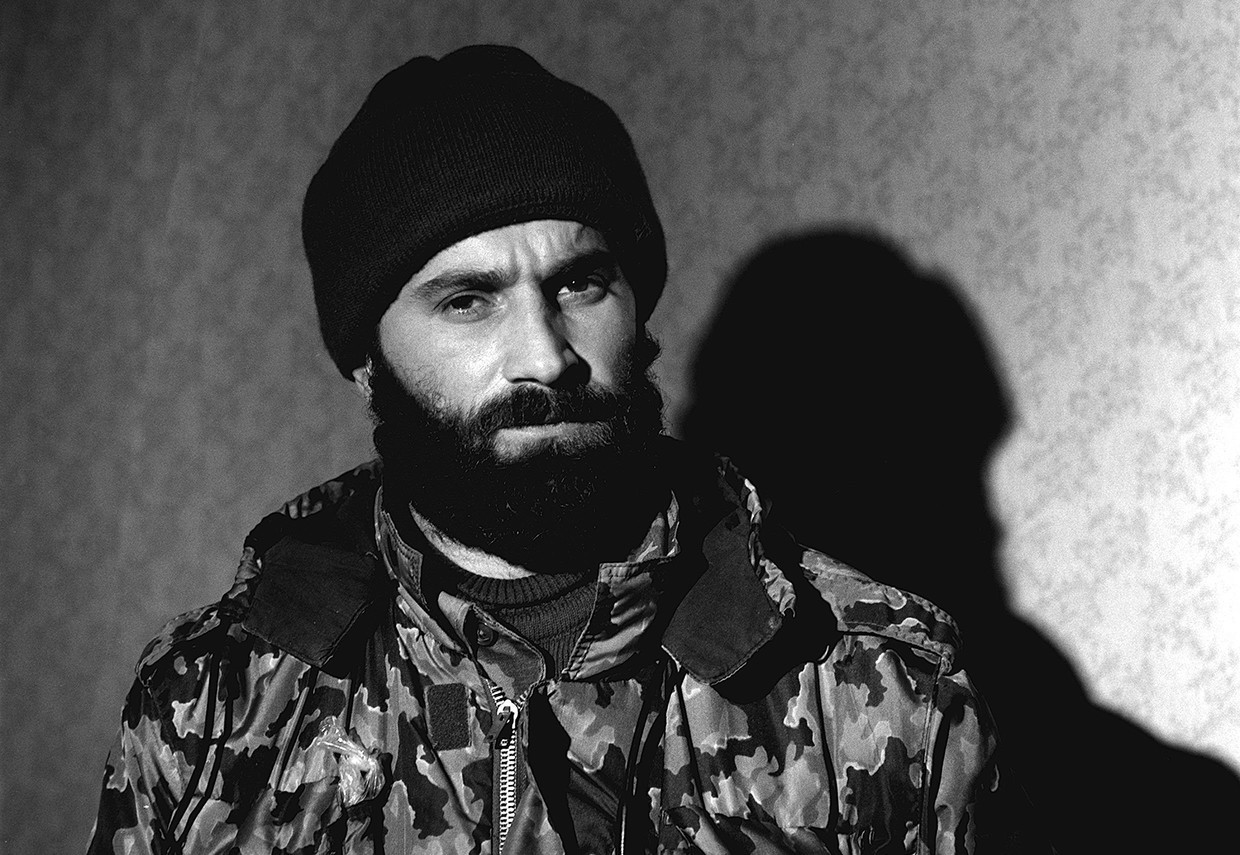

As the Soviet Union was disbanding in 1991, Chechnya, a republic in southern Russia with a population of around one million people, unilaterally declared independence. What had begun as a quest for national sovereignty quickly turned into an ethnic cleansing of the local Russian population and political purges of Chechens who opposed the new regime. In 1994, Russia launched a military operation against militants in the region. This led to a war that lasted until 1996, when the two sides reached a ceasefire agreement and Russian troops withdrew. By this time, the conflict had become increasingly brutal. The turning point came when Chechen guerilla leader Shamil Basayev seized a hospital in the city of Budyonnovsk, taking many people hostage.

However, the ceasefire didn’t last long. Whereas until 1996, the conflict revolved around Chechen nationalism and the republic’s right to self-determination, soon it attracted the attention of global terrorist networks, including Al-Qaeda. In 1999, the war resumed – this time under the banner of global jihad. Basayev, along with Arab jihadist fighter Khattab invaded the neighboring republic of Dagestan, where they faced fierce resistance from local militias and the Russian army. The incursion failed, and it led to Moscow’s forces re-entering Chechnya.

Starting in 1999, a grueling guerrilla war unfolded. Russian forces faced tactical setbacks but gradually wore down the Islamist detachments. Basayev became a prominent guerilla leader and reverted to the age-old tactic of terrorism. In 2002, a theater in Moscow was seized during a performance. Half of the 44 terrorists participating in the attack were female suicide bombers equipped with explosive belts. The hostage rescue operation was extremely challenging, and 129 out of the 916 hostages ended up dying. Unlike in Budyonnovsk, however, the attackers were neutralized.

The terrorists continued to target civilians in Russia, organizing terrorist and suicide attacks in public spaces, but they did not obtain the desired result of paralyzing Russian society. Instead, they galvanized support for decisive action. Soon, Basayev came to believe that he needed to carry out a large-scale attack to turn the tide of the war. It’s important to note that the actual president of Chechnya who represented the republic internationally was not Basayev but Aslan Maskhadov.

Maskhadov, who had become a militant after many years of service in the Soviet army, was elected president in 1997 through what had the appearances of a democratic process. He had managed to convince people that he was able to do more than just shout religious slogans. He also did not directly participate in large-scale terrorist attacks. The problem, however, was that Maskhadov lacked real power and influence with the terrorists; he was more of a figurehead, while hardline fanatics and criminals stood behind him. However, he was an essential figure – without Maskhadov, the armed underground movement in the Caucasus would have been nothing more than a provincial version of Al-Qaeda. His relations with Basayev were very cool, but the two were bound together and couldn’t do anything about it.

Basayev concentrated all his forces to carry out a series of large-scale acts of terrorism in 2004. These attacks happened all over Russia – at metro stations, police stations both in Chechnya and elsewhere, and even in airplanes – female suicide bombers blew up two passenger planes simultaneously.

But all of this was merely a prelude to an even more horrific event.

Since the goal wasn’t just to take hostages but to carry out a monstrous attack, the terrorists decided to seize an entire school. Basayev and his associates knew that the authorities would want to rescue the children at any cost. Meanwhile, it was impossible to secure every school in the country from a heavily armed terrorist group.

Preparing for an attack

Why did the terrorists choose Beslan? This small town is located in North Ossetia, one of Russia’s many national republics. It’s close enough to Chechnya that the terrorists wouldn’t have to travel far. The Ossetians are primarily Christians, which meant that Basayev, who was an Islamist, would feel little compunction about what was to be done to them. Moreover, North Ossetia has a long-standing conflict with neighboring Ingushetia that saw many killed in brutal ethnic clashes in the 1990s. The Ingush are closely related to the Chechens. Basayev recruited a number of Ingush people into the terrorist group that was responsible for seizing the school. Many of them joined the underground terrorist movement. Basayev’s plan was to incite a new ethnic massacre in the Caucasus.

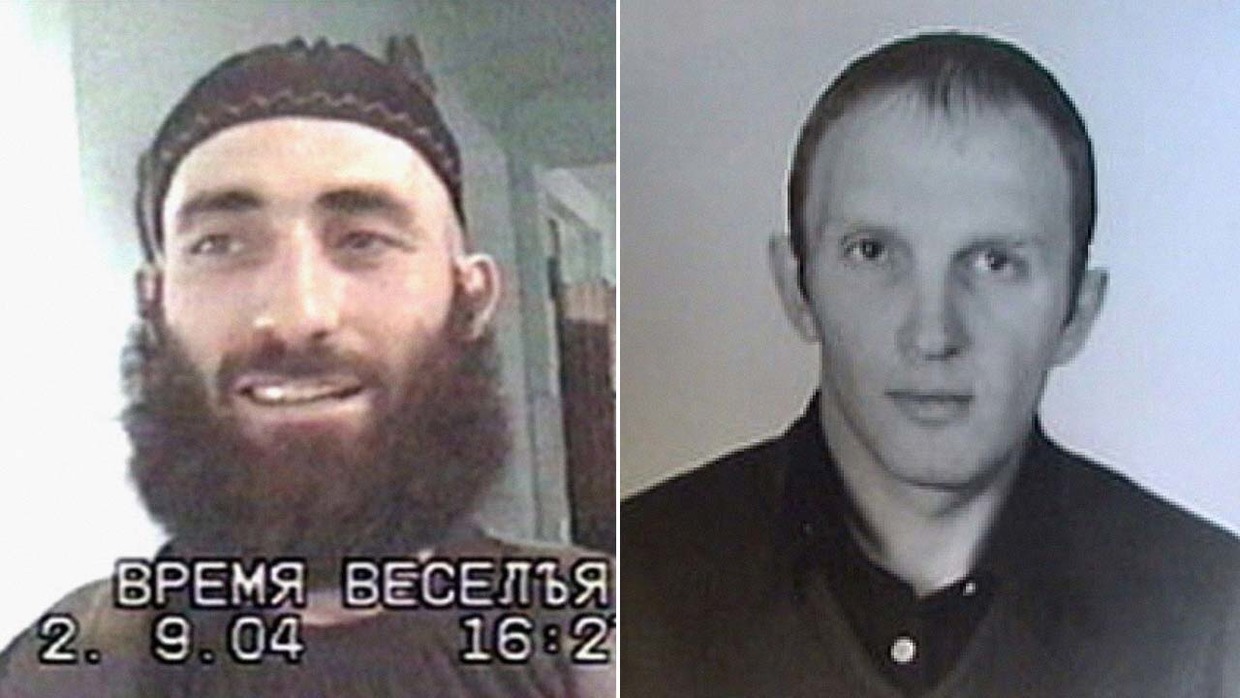

To provoke an ethnic conflict, Basayev appointed Ingush militant Ruslan Khuchbarov as the leader of the terrorists. Khuchbarov was at first an ordinary criminal without ideological motives but later became an Islamist. In 1998, during a business meeting with competitors, he shot two of his partners. He then fled and became a terrorist.

Vladimir Khodov was another sinister figure in the terrorist group. He was the only Slavic member but had an Ossetian stepfather. Like Khuchbarov, he became a militant to escape criminal charges – in this case the gang rape of a minor. However, the terrorists recruited him not because of his criminal background but because of his practical skills: Khodov spoke Ossetian fluently, was familiar with North Ossetia, and had lived in Beslan for a long time. He was most likely the one who suggested seizing School No. 1 and ended up becoming Khuchbarov’s right-hand man.

It wasn’t easy to choose the right target, but the ill-fated institution had several distinctive features. First of all, a small town was chosen because there would not be a large police force capable of quickly intervening. School No. 1, meanwhile, had a large enrollment and a closed-off courtyard, which made it difficult for anyone to escape during the attack – and also made it easy for the terrorists to defend themselves.

A total of 30 people were in the group besides Khuchbarov and Khodov. Most of them were Chechens and Ingush but there were also a few Arabs. There were also two female suicide bombers equipped with explosive belts. While most of the group were hardened criminals, a few, including the two women, were recruited at the last moment to stand guard, help the terrorists, and be disposed of. These people realized where they were being sent only at the last moment.

Some time before the attack, the group assembled in a camp in a secluded forested area near the village of Psedakh in Ingushetia, about 30km from Beslan. They planned to attack the school on September 1, when the academic year traditionally starts in Russia and not just students but entire families gather for what is essentially a celebration of the beginning of the new school year.

How the three-day horror began

Early that morning, the terrorists set out with a vast arsenal that included assault rifles, machine guns, grenade launchers, and numerous homemade bombs. They crammed together into a so-called Shishiga – a small army GAZ-66 truck. They avoided major highways and mainly drove through abandoned country roads where they encountered few other vehicles.

The authorities had received vague intelligence about an impending terrorist attack but lacked specific details. The terrorist threat level in the North Caucasus was constantly high, but nothing like this had ever happened in Beslan. After years of warnings about possible attacks – some of which had never occurred – the vigilance of the local police had dulled. The terrorists encountered only one patrol officer on their way to Beslan, whom they took hostage.

At 9am, as the start of the school year celebrations began at School No. 1, the militants drove up to the facility. A student named Agunda Vataeva was chatting with her friends when she suddenly heard gunfire. Turning her head, she saw boys fleeing from a bearded man who was holding an automatic weapon and firing it into the air. Agunda thought it must be a bad joke, while another boy, Georgiy Ilyin, assumed it was just balloons popping.

The school was seized. The terrorists positioned themselves at the narrow entrance to the school’s courtyard, leaving no chance for anyone to escape. The local police station was close by, and police officers rushed to the scene almost immediately, managing to shoot one of the attackers. However, the officers stood no chance against 30 armed men.

Some older students who quickly understood what was happening managed to escape by jumping over the fence into a neighboring yard. Amid the chaos, the elderly boiler operator, Ivan Karlov, hid several children in the boiler house. While confusion reigned outside, he and some older students broke through the flimsy outer wall. By the time the terrorists figured out what was happening and looked inside, 17 people had managed to escape. Karlov, however, did not make it – he was taken hostage and was soon killed.

In total, the terrorists took 1,128 hostages, most of whom were children.

From the very beginning, the terrorists behaved brutally, killing anyone who demonstrated the slightest sign of defiance. One man, Ruslan Betrozov, tried to calm the panicking crowd by speaking in Ossetian. As soon as he finished speaking, he was shot dead, right in front of his two sons.

In the courtyard, scattered belongings lay everywhere – flowers, torn clothing, and school supplies. Among them was a video camera that had been dropped by one of the parents. One of the militants picked it up and started recording the events which unfolded in the school over the next few days. He didn’t bother to change the tape, so this horrifying footage remained with the original title, ‘Fun Time’.

Read about what happened next here: