A video-game war No. 1: ten years since the NATO bombings of Yugoslavia

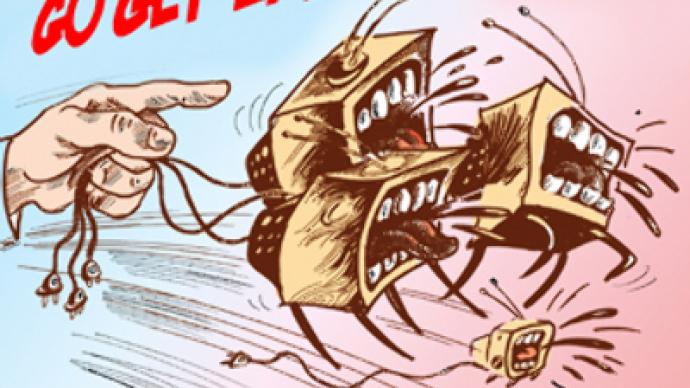

Modern wars are fought live on television.

They already look like war movies: there are multiple cameras showing the same events from several different angles and we can often hear what the people on the screen are saying. With the 3D and advanced animation technology, modern video games look practically the same as real wars and war movies.

Soon the slightest difference in the image that is still left will disappear and we will totally lose the capability to tell a real war from a video game, and that from a war movie. At least until the day a bomb falls on our house while we are watching its progress all the way down from the open hatch of a bomber aircraft to our roof, live on our living room TV set.

The NATO air war against Yugoslavia was probably the first war shown live on TV in its entirety. 78 days and nights, 24/7 on CNN, BBC, and every other channel that had enough money to organize the transmission. Most couldn’t afford it, so the world had to rely solely on the ‘Big Guys’ of television to stay informed about the goings-on of the conflict.

Informed… Where information ends and perception – or misperception – starts? In other words, where’s the beginning and the end of media spin in straightforward, detailed, live, meticulous 24-hour television coverage? Is it in the picture? Or in the voice-over? Both, probably. Because the picture comes from a camera held by a person who has perceptions and misperceptions, and from the lens on that camera which he trains on things according to his perceptions and misperceptions. For a voice-over it is even easier: a thought pronounced aloud is already a lie…

I remember the time before e-mails. Waiting for weeks for a letter from that closest and dearest person in your life. The disappointment felt regularly once or twice a day when you open the mail box and find newspapers galore and no letters. The pure joy when one day you open it and see the letter, definitely that very letter you have been waiting for, and the drumming of the heart in your scull and ears when you read the first lines for the first time.

Several years ago I found myself again in such a situation, but this time I could exchange e-mails with my far-away correspondent several times a day, chat in ICQ and call on IDD. That was a torture for both of us, and it ended in a total disaster. The modern media gadgets destroyed our respect for the ten-thousand mile distance between us and turned us into maniacs constantly meddling in each others’ daily affairs. The combination of physical distance and virtual closeness finally killed the feelings that had seemed unshakeable before the separation.

Something akin to that happens when war comes into our homes through live television. Important matters shrink and unimportant ones get blown up and change the picture of a real event into a picture of something distant and unreal, or too close to home. The first time I watched an armed conflict live on CNN was in October 1993 when government troops were advancing on the opposition-held White House of Moscow, the current premises of the Russian government. I shared a big empty hotel in Pattaya with a U.S. Air force crew flying off the Utapao naval base and we gathered in the hall of our floor to watch the event on a large-screen TV set.

We sat there through the whole thing: the shelling, the storming, the refusal of some units to attack and the readiness of others. The fires and the stray bullets. The crowds of fearless onlookers who were dying of the strays but refused to move to a safer place. The reaction of my fellow-watchers in American uniform surprised me greatly: they said, how can our (meaning the American) president allow this to happen in Moscow?!

But on the second thought it didn’t sound all that strange: for us at that moment America was the leader of the world that we aspired to join, and the battle in the center of Moscow was exactly about that – are we going to join that world or start a backwards march… The feeling the transmission created was just that: how can America let it happen!? Only when it was all over, it suddenly fell on me: what about the legitimacy of such a thing as direct interference in internal affairs of a sovereign state? My state. My country.

We were naïve then. I mean, we still believed that Russia could be seen by the West as an equal partner automatically, just because it has shed the Communist clothes and left them behind, dressing itself in the colors of democracy and freedom and getting drunk on the freedom air. Six years later, in 1999, when the bombs started falling off NATO aircraft and plunging towards military and civilian targets in Yugoslavia, all that live on our TV screens, the illusions dissolved.

Russia, the nation best acquainted with the Serb culture, was flat against the bombings, and nobody even paused to listen to what we had to say. Instead we were sentenced to watch day after day how those bombs were falling and falling… The images of the bombings were shown much more often than images of the supposed Serbian genocide of ethnic Albanians. There wasn’t enough footage of the alleged Serb atrocities, and most of what was shown later turned out to be the footage of the Kosovo Liberation Army soldiers mistreating the Serbs.

Even the ‘mass graves of Kosovo Albanians who fell victim to Serb atrocities’ in many cases proved to be populated by the bodies of Albanian combatants killed in action all around Kosovo and for some reason or other brought to a certain spot to be buried. And how many Serb refugees were shown leaving their homes and fleeing the theater of war with voice-overs calling them Kosovo Albanians? How many pictures of refugee camps separated from the outer world by irregular pieces of barbed wire were passed for images of concentration camps?

The images stuck, like a song sticks to your mind when you hear it on the radio every day several times. And that was the important part, because while the bombings went on it was necessary for those who conducted them to keep the popular sentiment high on the adrenaline of a visibly legitimate attack on the ‘bad guys’ who looked on TV worse than Hitler with his camps and his SS.

Downshifting was the slogan of the moment just a few months ago, before the crisis. People downshifted to get away from the hustle and bustle of corporate jobs. What happens when a war is shown on TV is also downshifting – or downgrading maybe, of pain and death, of fire and dust and dirt mixed with blood, of the sound of a falling bomb, of the shock of a torn limb. Live TV downshifts it all to video-game quality, and war loses its atrocious character and becomes a show.

In Yugoslavia in 1999 things were turned inside out by the spin-driven live TV coverage: whatever the Serbs had allegedly done to the Albanians before the bombings was blown way out of proportion, was twisted and spun to such an extent that it acquired the image of universal evil. Whatever was definitely and massively done by the bombings to the Serbs and the Albanians alike, looked like a 78-series space opera, interesting, at times violent, but harmless.

After a while the world population – or rather, a part of it (the other part is still dreaming the TV dreams of ten years ago) finally woke up to the reality left on the Serbian soil by the NATO raids, as well as to the great work of spin done on the ethnic angle of the Serb-Albanian conflict in Kosovo. But it was too late. The spin did its job perfectly: the only thing left to be done for its authors was to pronounce Kosovo’s independence. Which they promptly did.

In a 2006 interview Noam Chomsky quoted a book written by a high official of the U.S. administration who had served during the bombings of Yugoslavia: ‘The country…was the last corner of Europe which had not subordinated itself to the U.S.-run neo-liberal programs, so therefore it had to be eliminated.’

A Russian columnist wrote today in IZVESTIA: “Yugoslavia was bombed for Kosovo. Russia wasn’t bombed for South Ossetia. There is only one reason for that: Russia had the nukes while Yugoslavia hadn’t.”

Aren’t these two quotes saying the same thing?

Evgeny Belenkiy, RT.