Europe points war crime finger at Russian veteran

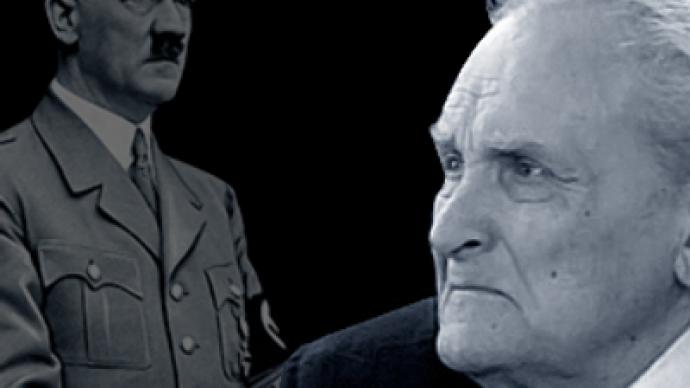

In what is seen as a politically motivated gesture, the European Court of Human Rights has delivered its verdict in the case of Vasily Kononov versus Latvia.

The former Soviet Republic accuses Kononov – a veteran of the Second World War who holds Russian citizenship – of war crimes.

Case description

After the European Court’s verdict was delivered by a majority vote of 14 against 3, with the chairman of the jury Jean-Paul Costa and judges from Moldova and Montenegro voting in favor of the Russian veteran, this controversial case is raising many questions about the fairness of dragging through endless courts a man whose 90th birthday is just around the corner, a man who served his country in the bloodiest battle in Soviet history, and who has been accused of committing war crimes by Latvia’s government, after having earlier received several honorable orders by the Soviet government for his heroism in the war.

All of this comes as Russia marks the 65th anniversary of the Second World War, commemorating the Soviet defeat over Nazi Germany.

So why would the Baltic State sue the veteran?

Background

In 1998, the now-88-year-old war veteran was arrested on charges of killing nine allegedly innocent people in 1944 during the Second World War. Since then, pensioner Kononov spent his days in and out of court. In total, he has been tried six times and put in prison for two years.

Kononov, 88, fought against the Nazis in his native Latvia as a Soviet resistance fighter.

In February 1944, Nazi troops surrounded and burned down a barn in Latvia, killing 12 partisans sheltering inside, including two women and a baby.

Kononov says the Nazis were tipped off by collaborators among the locals and the police.

“They persuaded the partisans to stay for the night but the police chief sent his deputy to the Germans when the partisans went to sleep. German soldiers encircled the barn, there was a fight, and then the Nazis set it on fire,” said Kononov.

After a tribunal, his partisans tried and executed nine Latvian villagers who, according to him, were armed collaborators, and traitors, who were behind the deaths of the partisans killed in the barn fire. Latvian officials, however, claim that the people killed were unarmed civilians and have dubbed Kononov a war criminal.

“We have only testimony that Germans provided local people with arms for their self-defense. But in the moment that Kononov and others were killing them, they weren’t resisting,” said Ritvar Janson of the Latvian Museum of Occupation.

During the Second World War, Kononov had lost most of his family members – his parents and aunt were sent to concentration camps in Germany. His uncle and cousins were killed in combat.

Vasily himself was wounded many times, suffered shellshock twice and needed three operations for his injuries after the war.

“In my partisan squad I was an explosives expert. I was responsible for blowing up 42 military targets, including 16 supply trains. I saved the lives of many people in Latvia,” said Kononov.

Opposite decisions – previous and latest court hearings

In 2008, the European Court of Human Right’s Lower Chamber ruled that the Latvian judges’ decision to jail Kononov had no basis under international law, and awarded him 30,000 euros in damages. It was said that Article 7 of the European Convention on Human Rights had been violated when the man was found guilty of war crimes in 1998.

This article in the Convention states the following: “No one shall be held guilty of any criminal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a criminal offense under national or international law at the time when it was committed.”

In simple terms, this means a person cannot be tried for a crime which was not officially defined as a crime at the time it was carried out.

The Latvian government didn’t want to settle for the ruling proclaiming Kononov’s innocence, and had appealed.

Strasbourg set off to look at the 12-year-old legal saga once again.

At the hearing on May 17, the same Court – but a higher Chamber – said that the lower Chamber (that had come to the verdict of innocence) had come to the conclusion that the Latvian side had actually not violated Article 7 of the European Convention on Human Rights, as it had been defined in the court’s first decision taken in 2008.

Thus Kononov has – again – been named guilty by the European human rights judicial body of the war crimes he was accused of by Latvia.

Re-writing history

Analysts say attempts to rewrite history have been on the increase coming out of the Baltic republics in the last couple of years. Former Soviet Republics – such as Estonia and Latvia – have on a number of separate occasions become home to attacks on monuments of Soviet soldiers, and similar episodes of attempts to present the Soviet liberation of their territories in the Second World War as occupation.

Some ethnic Latvians view the Soviet Union as just another occupying power and see those who fought against it, even if they fought with the Nazis, as freedom fighters.

These latest attempts to wave the term “genocide” in the face of an 88-year-old war veteran are being seeing by some experts as politicized bias.

The episode of the killings – which some have labeled war crimes and others genocide – occurred in February 1944.

This took place around the time when the term “genocide” was just being coined by Polish–Jewish scholar Raphael Lemkin all the way across the globe.

Legally, the term was defined for the first time only after the creation of the United Nations in 1945 – a year after the killings Kononov is being accused of. In 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide which legally defined the crime of genocide for the first time in history.

As for the term “war crimes”, Vasily Kononov’s lawyer and other respected experts have called the Kononov vs. Latvia trial an attempt to set up a so-called “anti-Nuremberg” trial. The difference is that during those trials – Nazis were sued for their actions in the Second World War, when Kononov is being sued for fighting the Nazis the best way he must have known how.

“This case was totally politically-motivated. The plan was to start a sort of anti-Nuremburg trial and the problem is that those who escaped Latvia with the Nazis have now returned and are the ones in power,” said Eduard Gonzharov of Latvian Anti-Fascist Committee.

Other experts have said that the accepted statute of limitations in this human rights case has expired under national Latvian law; others have argued that international law says that there is no such thing as an expiration date on war crimes.

The Russian Foreign Ministry has condemned the Strasbourg Court’s ruling, Interfax news agency reports.

“This ruling is difficult to understand. We have just marked the 65th anniversary of the victory in World War II. It is surprising that such rulings are passed against those who were fighting against fascism,” the ministry told Interfax.

Latvia’s large ethnic Russian community, as well as Russia, says the controversial case is an attempt to belittle the Soviets’ role in liberating Latvia.

Some have gone so far as to name the courts’ decision a catastrophe, casting a shadow of shame on Europe.

And the question remains of how much of a shadow this decision will cast on not just war veteran Kononov, but the other former soldiers – and now war veterans – who gave away their youth to defeat fascists. With less and less veterans around every year to share the experiences and real stories of those dark days, the big “if” is whether or not creating such a legal precedent comes at the worst possible timing.

Anastasia Churkina, RT Correspondent

Read also – European Court of Human Rights Humiliates Soviet War Veteran