Russia in focus – the challenges we must face

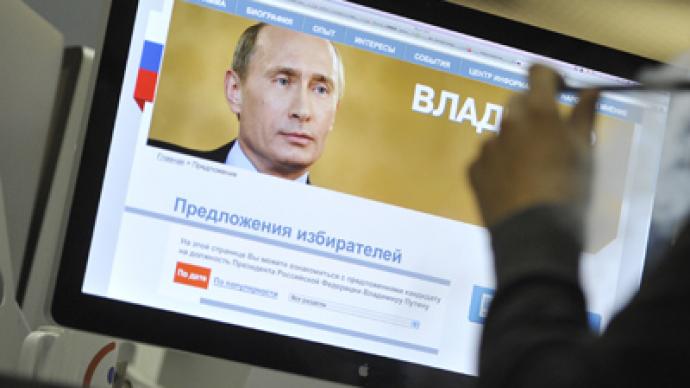

In view of the forthcoming presidential elections, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin detailed his program in an article published by the popular daily Izvestia. Here is the full translation of the article.

On March 4, Russian voters will go to the polls to elect the country’s president. Today, many debates are unfolding across society. I find it necessary to express my position on a number of issues that I consider to be important for public discussion. What risks and challenges will Russia be forced to face? What should be our position in global politics and economy? Will we follow the development of events or take part in creating the rules of the game? What resources will allow us to strengthen our positions and, allow me to emphasize – ensure stable development – one that has nothing to do with stagnation? Because in the modern world stability is something that can only be achieved through hard work, by being open to change and ready for long-overdue, well-planned, and well-calculated reforms. A recurring problem in Russia’s history is the desire of part of the elite to take a leap towards a revolution, rather than for sequential development. Meanwhile, not only does the Russian experience but that of the entire world show the destructiveness of historic leaps: haste and destruction without creation. This is confronted by another trend, an opposite challenge – the inclination toward stagnation, dependency, non-competitiveness of elites and a high level of corruption. Moreover, at every convenient moment, right before our eyes, the “subversive” individuals turn into “self-righteous lords”, who resist change and jealously guard their status and privileges. Or a reverse process happens: the “lords” become “subversive” individuals. Hence the “short breath” of politics, its limitation to issues concerning the ongoing preservation or redistribution of power and property. This situation has traditionally been engendered by weak public control of politicians and the underdevelopment of civil society in Russia. The situation is gradually changing, albeit very slowly. There can be no real democracy without a policy that is accepted by a majority of the population and which reflects the interests of that majority. Yes, it is possible to captivate a large part of society with loud slogans and images of a wonderful future, but if later people do not see themselves in that future, they will turn away from politics and common challenges for a long time. This has already happened in our history a number of times. Today, there is talk about various ways of renewal of the political process. But what are we being asked to agree on? On ways to organize leadership? To transfer it to “the best people”? And then what? What will we actually be doing? I am concerned about the fact that there is practically no discussion on what should be done outside of elections, after elections. In my opinion, this does not meet the interests of the country, the quality of development of our society, or the level of its education and responsibility. Russian citizens, I think, should be given the opportunity to not only discuss the merits and shortfalls of politicians – which in and of itself is not a bad thing – but also the content of policies, the programs that various political actors plan to implement; the challenges and goals that should be the focus of these programs; ways we can improve our lives, creating a more equitable social structure; and the vector of preferred economic and social development. There needs to be an extensive dialogue about the future, our priorities, the long-term choices, national development and national prospects. This article is an invitation to this dialogue.

Where we are and where we are going

Today, based on the general parameters of economic and social development, Russia has emerged from the deep recession that followed the collapse of the totalitarian model of socialism and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union. Despite the crisis of 2008-2009, which has “taken away” two years from our efforts, we have reached and surpassed some of the best indicators of living standards in the Soviet Union. For example, life expectancy in Russia is already higher than in the Soviet Union in 1990-1991. A developed economy is, above all, the people, their work, their income, and the number of new opportunities. Compared to the 1990s, the poverty level has been reduced by more than 2.5 times. “Stagnant poverty zones,” when capable and active people in large cities could not find a job or were not paid their salaries for months, have practically become a thing of the past. According to independent research, the real income of four out of five Russian citizens exceeds the level of 1989 – the “peak” of development in the Soviet Union, which was followed by the collapse and destabilization of the country’s entire socio-economic body. Today, more than 80 per cent of Russian families have a higher consumption level than the average level of a Soviet family. The availability of household appliances has risen one and a half times to the level of developed states. Every second family has a car, a three-fold increase. Living conditions have improved significantly. Not only the average Russian citizen, but also our retirees as well, are currently consuming more staple foods than in 1990. But most importantly, over the last 10 years a significantly large stratum of people has formed in Russia which, in the West, is considered to belong to the middle class. These are people with incomes that allow a sufficiently wide range of choices – to save or to spend, what to buy, and how to manage leisure time. They can choose the types of jobs that they like and they have a certain amount of savings. And finally, the middle class are people who can choose policies. Their level of education is usually such that it allows them to have an informed opinion on the candidates, instead of “voting with the heart”. Incidentally, the middle class has begun to really articulate their needs in various sectors. In 1998, the middle class accounted for 8-10 per cent of the population – that’s less than in the later years of the Soviet Union. Today, based on various estimates, the middle class constitutes 20 to 30 per cent of the population. These are people whose incomes are more than three times higher than the average earnings in 1990. The middle class must continue to grow, to become a social majority in our society and to expand, made up as it is of those on whom the country depends, such as doctors, teachers, engineers and other skilled workers. Russia’s main hope is the high level of education of the population and, mainly, of our youth. And that is a fact, despite all the well-known problems and complaints about the quality of the national education system. Fifty-seven per cent of our population aged 25-35 have completed higher education. Besides Russia, a similar level is found in only three other countries: Japan, South Korea, and Canada. The explosive growth of educational needs continues. When it comes to the next generation (aged 15-25), it is fitting to talk about universal higher education, with more than 80 per cent of our young men and women obtaining or seeking it. We are entering a new social reality. The “education revolution” is fundamentally changing the very image of Russian society and Russia’s economy. Even if today our economy does not require so many workers with higher education, it is already impossible to turn back. It isn’t the people who need to adjust to the existing structure of the economy and the labor market, the economy must become such that citizens with higher education and a higher level of demands are able to find decent work. Russia’s biggest challenge is learning to apply the “educational drive” of the younger generation, to mobilize the increased demands of the middle class and its readiness to be responsible for its prosperity in ensuring economic growth and the country’s stable development. Having better-educated people means longer life-expectancy, lower levels of crime and anti-social behavior and more rational choices. All of this, in itself, already creates a favorable environment for our future. But this alone is not enough. During the last decade, the rising prosperity level has been largely made possible by the government’s actions, including its restoration of order in the distribution of natural resource royalties. We used oil revenues to increase personal incomes, in order to bring millions of people out of poverty, as well as to have national savings in the event of crises and catastrophes. Today, the potential of the “natural resource economy” is running out and, most importantly, has no strategic prospects. In the base policy documents of 2008 adopted immediately before the crisis, economic diversification and the creation of new sources of growth were outlined as among the main goals. A new economy needs to be formed for educated and responsible people according to their various requirements and characteristics, whether as professionals, entrepreneurs, or consumers. Over the next 10 years, another 10-11 million young people will enter the labor market, of whom 8-9 million will have higher education. Already today, 5 million skilled workers on the labor market are dissatisfied not only with their wages, but also the nature of their work and its lack of prospects. Another 2-3 million are professionals working in budgetary institutions, who are looking for new employment. Moreover, 10 million people are employed by factories, built with archaic, backward technologies. These technologies must become a thing of the past – and not only because they are losing out in the market. Some of them are simply a health hazard for workers and the environment. So the creation of 25 million new, high-tech, well-paid jobs for people with higher education is not phrase-mongering. It is an urgent necessity – a minimum level of sufficiency. To meet this national goal, we need to build a state policy, consolidate the efforts of the business sector, and create the best possible business climate. I am confident that today’s – and especially tomorrow’s – talent pool in our country makes it possible to claim some of the strongest positions in global economic competition. Russia’s future economy must meet the needs of society. It must ensure higher wages, more interesting, creative work, more opportunities for professional growth, and create social ladders. It is this – and not only GDP indicators, volumes of foreign currency and gold reserves, international agencies’ ratings, and Russia’s high ranking among the world’s largest economies – that will be critical in the coming years. Most importantly, people must feel a positive change and, above all, do so by expanding their own capabilities. But the engine of growth must be and will be the people’s initiative. We are sure to lose if we rely solely on the decisions of officials and a limited number of large investors and state-owned corporations. We are sure to lose if we rely on the passive position of the population. So, Russia’s growth over the next decade equals the extension of freedoms for each and every one of us. Prosperity from handouts without self-responsibility is simply no longer possible in the 21st century.We are faced with yet another challenge. Behind the general statements about cohesion and the benefits of benevolence hide people’s lack of trust in one another, their reluctance to engage in public affairs, take care of others, and their inability to rise above personal interests – which is a serious and a deep-rooted ailment of our society. In Russian culture, there is a great historical tradition of respect for the government, public interests – things that the country needs. The absolute majority of Russians want to see our country as being great and strong and respect the heroes, who have devoted their lives to the common good. But, unfortunately, pride in the nation is far from being regularly expressed in people’s daily lives through participation in local government, readiness to act in protection of the law, or real charity. Indifference and selfishness are not typically the reason for this, but simple self-doubt or lack of trust in one’s neighbor. But even here in recent years, the situation has been gradually changing. Citizens are increasingly more often choosing not to limit themselves to fair demands to the leadership, but are taking many of the mundane, yet very necessary, tasks into their own hands: landscaping, caring for the disabled, helping the needy, working on children’s recreation activities and much more. Starting in 2012, the government will begin supporting such initiatives. Support programs for community-oriented non-governmental, non-profit organizations have been adopted at the federal level and in many regions. In future, we will greatly increase the scale of such programs. But in order for them to truly work, it is necessary to take a hard stance against the prejudice against community workers that prevails in the bureaucratic environment. This prejudice is the reason for not wanting to share resources, the desire to avoid competition, as well as the fear of a real demand for assignments. An invaluable role in social service, overcoming dissociation among people, the formation of trust and readiness for peaceful resolution of conflicts, which are inevitable in a rapidly developing society, is played by traditional religions such as Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism. Much in this regard can and should be done by schools and mass media, television, and the online community. A society of free people is not the same as a crowd of individualistic, calculating egoists, indifferent towards the common good. We never were and never will be this crowd. Personal freedom is productive if you remember and think of others. Freedom without moral foundations turns into arbitrariness. Trust between people is formed only when society is held together by common values and people have not lost the capacity to have faith, honesty and a sense of justice. Meanwhile, respect for the law is formed only when it is the same for all, obeyed by all, and is founded on the truth. The social portrait of our future will not be complete without addressing another important issue: for various reasons 10-11% of our population remains below the poverty level. By the end of the current decade, this problem must be resolved. We must overcome poverty, which is unacceptable for a developed country, using both state resources and community efforts – the engaged, active part of the population. We need to give the public assistance system a purposeful character and support the philanthropy movement. A system of social mobility, social ladders corresponding to modern society, needs to be formed in Russia in its entirety. We need to learn to compensate for the negative social consequences of a market economy and its organically engendered inequality – the same way as countries that have long lived under capitalism have done. This includes special, unique educational support, which will be received by children from underprivileged families. It’s social housing for families with the lowest incomes. It’s putting an end to discrimination against the disabled and ensuring their equal access to all of the life essentials and decent work. Society will be successful only when our citizens no longer doubt its fairness.

A new stage in global development

The global crisis that erupted in 2008 has affected everyone, subjecting much to re-evaluation. It is no longer a secret that the economic storm was not only provoked by cyclical factors and regulation failures. The root of the problem is in the accumulated imbalances. The model – built on unrestrained borrowing, on living in debt and eating away the future, on virtual rather than real values and assets – has come to a dead-end. Moreover, the generated wealth was and is being extremely unfairly distributed between countries and regions. This also reduces global stability, provoking conflicts, decreasing the ability of the global community to come to agreements on critical, fundamental issues. False realities are not only manifested in the economy, but politics and the social sphere as well. Here, too, we are seeing a type of illusionary “derivatives”.The crisis in the developed countries has revealed one dangerous, in my opinion, purely political trend: the government’s unreserved, populist build-up of social obligations – without any connection to raising labor productivity – a trend toward social irresponsibility. However, now, many are seeing that the era of states’ prosperity “off the sweat of someone else’s brow” is coming to an end. No one will be able to live better than what their work allows them. This fully applies to Russia. We did not play with “dummies”. Our economic policy has been well-planned and prudent. In the pre-crisis period, we had significantly increased the volume of the economy, got rid of debt bondage, raised people’s real wages, and created reserves, which have allowed us to get through the recession with minimal losses to the people’s standards of living. Moreover, in the midst of the crisis, we were able to significantly increase pensions and other social benefits. Meanwhile, there were many, particularly among the opposition, who were pushing us to quickly spend the oil revenues. What would have happened to people’s pensions had we taken the populist route?Unfortunately, the populist rhetoric was sounded in the recent parliamentary election campaign. We will most likely hear it during the presidential campaign as well – it will come from those who are not expecting to win and are, therefore, readily making promises that they will not have to keep. I will be frank: we must continue to insistently use every possible avenue to improve the lives of our citizens but, just as before, we cannot act “at random”, in order to – unlike in certain Western states – avoid suddenly facing the need to rob people of so much more than was so frivolously given to them.It should be acknowledged that the scale of today’s global imbalances is such that they are unlikely to be eliminated within the current system. Yes, opportunistic market swings can be overcome. And many countries have already developed a number of tactical measures that allow, at varying levels of success, to respond to acute manifestations of the crisis. But on a deeper, longer-term level, today’s problems are by far not opportunistic. Generally speaking, what the world faces today – is a serious systemic crisis, a tectonic process of global transformation. It is a visible manifestation of transition into a new culture, a new economic, technological, and geopolitical era. The world is entering a zone of turbulence. And, naturally, this period will be long and painful. There is no need to harbor any illusions here.Also evident is the end of the system that had formed in the 20 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union – including the phenomenon of a “unipolar world”. Today, the formerly-sole “center of power” is no longer able to maintain global stability, and the new centers of influence are not yet ready to do so. The increased unpredictability of global economic processes and the world’s military-political situation calls for a trust-based and responsible cooperation between states – and mainly between the permanent members of the Security Council, and the G-8 and G-20 states. Continuous efforts need to be made to overcome mutual suspicion, ideological prejudices, and short-sighted egoism.Today, major economic centers – instead of serving as locomotives of development and providing stability to the global economic system – are increasingly more-often causing problems and risks. Social and ethno-cultural tensions are rapidly rising. In a number of regions, destructive forces are “developing” and aggressively letting themselves be known, ultimately threatening the security of the entire global population. Objectively, their allies are often the countries that are trying to “export democracy” with the help of force and military measures. Even the best of intentions cannot justify violation of international law and state sovereignty. Moreover, experience shows that the initial goals are usually not reached, while the losses greatly exceed expectations. In these conditions, Russia can and must play a deserving role, dictated by its civilizational model, great history, geography, and its cultural genome, which seamlessly combines the fundamentals of European civilization and the centuries-old experience of cooperation with the East, where new centers of economic power and political influence are currently rapidly developing. In the 1990s, the country went through a real shock of collapse and degradation, enormous social costs and losses. An all-out weakening of the nationhood was, in this situation, simply inevitable. We had indeed approached a critical point. The very fact that several thousand bandits – though supported by some external forces – had decided to attack a government with a million-man army speaks of the tragic nature of that situation. There were too many of those, who thought it was possible to finish us off.I very well remember the text of a message intercepted by the FSB that had been sent to his accomplices abroad by one of the most odious and cold-blooded international terrorists, who was responsible for the killings of our citizens in the North Caucasus – Khattab. He wrote: “Russia is as weak as ever. Today, we have a unique opportunity: to take away the North Caucasus from the Russians.” The terrorists had miscalculated: with the support of the Chechen and other peoples of the Caucasus, the Russian army was able to defend the territorial integrity of our country and the unity of the Russian state. However, we needed a great amount of effort and mobilization of all resources to dig ourselves out of the hole. To assemble the country. To restore Russia’s status of a geopolitical entity. To restore the social system and uplift the fallen economy. To restore basic governance. We were forced to restore the authority and the power of the state as such – and do so without deep-rooted democratic traditions, mass political parties, or a mature civil society, all the while facing regional separatism, rising dominance of the oligarchy, corruption, and sometimes blatant criminality in government agencies. The immediate challenge in these circumstances was restoration of the country’s unity. In other words, establishment of sovereignty of the Russian people, rather than the supremacy of individuals and groups, across its entire territory. Now, not many remember the difficulty of this challenge, the efforts required for its resolution. Now many remember that some of the most prominent experts and many international leaders in the late 1990s had agreed on one forecast for Russia’s future: bankruptcy and collapse. The current situation in Russia – if looked at through the prism of the 1990s – would have seemed to them as simply overly-optimistic fiction. But this “forgetfulness” and today’s readiness of society to hold Russia to the highest standards of living and democracy serve as the best evidence of our success. Because, in the recent years, we – the people of Russia – have made numerous achievements in resolving some of the pressing issues, the country has withstood the shocks of the global crisis. And today, we have the opportunity to talk about prospects and strategies. The time of restoration has passed. The post-Soviet stage in Russia’s development, just as in the development of the entire world, has ended and been exhausted. All of the preconditions necessary for moving forward – on a new basis and in a new way — have been created. Moreover, this has been done even in harsh, far-from-comfortable foreign political and foreign economic conditions. At the same time, the irreversible global transformation presents us with an enormous opportunity. And here, I would like to reiterate why I agreed to run in Russia’s 2012 Presidential Election. I do not want to, and will not, downgrade anyone’s achievements in the establishment of a new country. There have been many. But it remains a fact that, in 1999, when I became Chairman of the Government, and then President, our country was in a state of a deep systemic crisis. And it is the group of like-minded people, which was formed and headed by the author of these words, relying on the support of an absolute majority and national unity around common goals, that brought Russia out of the deadlock of a civil war, broke the backbone of terrorism, restored the country’s territorial integrity and constitutional order, revived the economy and, for the next 10 years, ensured one of the fastest economic growth rates in the world and increased our citizens’ real incomes. Today, we are seeing what has worked well, what has worked effectively, and conversely, what needs to be corrected, and what things needs to be abandoned altogether. In the coming years, I see our goal consisting of removal of everything that impedes our forward progression on the path of national development. This includes completing the creation of a political system, a structure of social guarantees and protection of citizens, and an economic model that together will constitute a single, live, constantly-developing, and at the same time stable and healthy state system. A system capable of unconditionally guaranteeing Russia’s sovereignty and the prosperity of the citizens of our great nation for decades to come. A system capable of defending the justice and dignity of every person; truth and trust in relations between the government and society. There are many challenges that remain unresolved. New, complex problems are emerging. But we are able to use them to our advantage, to Russia’s benefit. Russia is not a country that backs down from challenges. Russia is focused; it pulls itself up and responds to any challenge in a dignified manner. It overcomes trials and always prevails. We have a new generation of creative, responsible people, who see the future. They are already playing and will continue to play leadership roles in enterprises and entire sectors of the economy, government organizations, and the entire country. We are the only ones responsible for the way we respond to today’s challenges and how we apply our opportunity to strengthen ourselves and our position in the rapidly-changing world. In the coming weeks, I intend to present some more-concrete ideas on this topic for public discussion.