Manchester City’s European ban shows what happens when football clubs become petrostate tools

“War is a continuation of politics by other means,” as Prussian military strategist Carl von Clausewitz famously once said – but in the modern age that adage could increasingly be applied to football.

We live in an era in which football clubs are a continuation of the strategic ambitions of oil-rich states; in which geopolitical tensions are transposed onto the pitch; and in which countries seek to buy cultural capital by investing in teams in foreign lands.

Example A for all of the above could be Manchester City, a club bankrolled by the bottomless pockets of Emirati royal Sheikh Mansour, and which on Friday was slapped with a two-year ban from European competition by UEFA over breaches of Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules.

The details of the case are widely reported, but in a nutshell, City have been found guilty of deliberately inflating sponsorship deals between 2012 and 2016 to ensure they complied with FFP rules.

Instead of sponsorship money coming to City from corporations – which were in any case based in Mansour’s UAE homeland – it is said to have come directly from the sheikh’s pocket.

Also on rt.com Manchester City BANNED from UEFA Champions League for TWO YEARS for breaking financial fair play rulesThe details of the case – which was launched based on emails published by the Football Leaks organization back in 2018 – are strongly disputed by City, who will fight their corner at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) in Switzerland.

Despite the fact that City are not first-time offenders, having been handed a record fine of almost £50 million (US$65 million) back in 2014 for FFP breaches, they will still fancy their chances of least getting the ban halved to one year.

Small solace, however, given that significant damage has already been done.

There is uncertainty over how things will play out with manager Pep Guardiola, and the same doubt could extend to several of City’s galaxy of playing stars; clubs across the continent will be licking their lips at the prospect of enticing the likes of Guardiola, Raheem Sterling and Kevin de Bruyne away from the Etihad with the offer of guaranteed European football.

Also on rt.com UEFA has gone nuclear on Manchester City – and the fallout for European football will be massiveWin or lose their appeal – and they will throw their mammoth financial clout into defending themselves – it’s clear that City are confronted with major immediate problems.

But it’s when placed in the broader perspective that the ramifications from the Manchester City vs. UEFA showdown seem the most seismic – and pose the biggest questions over what football has, in many respects, become at its highest level.

City have been a club transformed since Abu Dhabi's Sheikh Mansour rolled into town in 2008, buying them for an initial £150 million and since pumping petro-cash in to the tune of well over £1 billion (US$1.3 billion).

That transformation has been on the pitch, where City have won four Premier League titles in the past decade, as well as two FA Cups and four League Cups.

But it has also come off it, with the redevelopment of the club’s training facilities and academy, and the regeneration of their part of eastern Manchester.

They are yet to win the ultimate prize – the Champions League – but are again among the favorites this season as they prepare to face Real Madrid in the last 16, with the first leg coming at the end of February.

City have, simply put, been supercharged into a football powerhouse.

But beyond taking issue with the finances that have enabled that ascent – as UEFA clearly has – it’s worth remembering what exactly underpins the desire of City’s wealthy backers to splurge on such a project in the first place.

A Premier League club is an attractive prospect these days, but for reasons far beyond simply being a footballing asset.

For those such as City's Abu Dhabi backers, it offers the chance to purchase a brand as cultural capital, to project a new image to the world (particularly in the face of criticism over human rights issues), and to bolster national pride – not least in the context of regional rivalries, such with as the similarly ambitious Qataris (more on them below).

It was likely opportunity, rather than affinity which brought Sheikh Mansour knocking to that particular part of Manchester in 2008.

Most Manchester City fans would – until now at least – have cared little about all of that. Their team has played sublime football, won titles, and has one of the best set-ups in world football.

They will also point to the fraught question of owners of various ilk all across Europe. Look no further than down the road and you will see Manchester United, a club with widely despised American owners, the Glazers, who are accused of moral bankruptcy by leveraging the club with debt to line their own pockets.

Also on rt.com 'In it for the long term': Manchester Utd exec insists US owners DO NOT plan to sell amid Saudi crown prince takeover talkBut in City’s case, while the oil money has always been there to muddy the waters, it has now spilled over into all-out war with UEFA.

Among City’s gripes will be that UEFA’s FFP rules are inherently unjust, and preclude “fairy-tale” stories such as theirs of a long-struggling club propelled into the elite by wealthy benefactors, only to be shunted back down by more established rivals who resent their upstart status.

Many Manchester City fans and members of the media have made exactly that point since Friday’s shock news (although with equally as many pointing out that, just because you don’t like the rules, it doesn’t mean you can flout them with impunity).

Another source of lingering resentment for City will be the perception that UEFA is waging a vindictive campaign against their club when others have escaped sanction.

The biggest parallels will be drawn with Paris Saint-Germain, whose rise has been similarly primed by petrodollars, in their case flowing from Qatar.

PSG have been scrutinized for their own financial dealings, not least in the wake of their world-record purchase of Neymar for €222 million and €180 million acquisition of Kylian Mbappe several years ago.

In PSG’s case, UEFA’s Investigatory Chamber found no FFP breaches – even to the astonishment of the organization’s own adjudicatory committee chairman, who was foiled with his efforts to launch another investigation.

The fact that PSG’S president, Qatari businessman Nasser Al-Khelaifi, is also on UEFA’s executive board has raised more than a few eyebrows – not to mention that he is also the chairman of the beIN Media Group, a lucrative payer for UEFA’s TV rights.

PSG’s rise under their Middle Eastern backers mirrors City’s in many ways; Al-Khelaifi’s Qatar Sports Investments took over the club in 2011, and has since poured in well over €1 billion to make the team Champions League contenders (although, as with City, they are yet to win the competition).

It’s unlikely that any in Qatar will shed tears that City have fallen foul of UEFA financial rules, given the enmity between the Qataris and City’s backers in the UAE – which was among the states to impose a blockade on Qatar in 2017 over accusations it supported terrorism.

Of course, PSG’s Qatari benefactors and Manchester City’s Abu Dhabi backers are far from football’s first mega-spending owners, and their rise has not occurred in a vacuum.

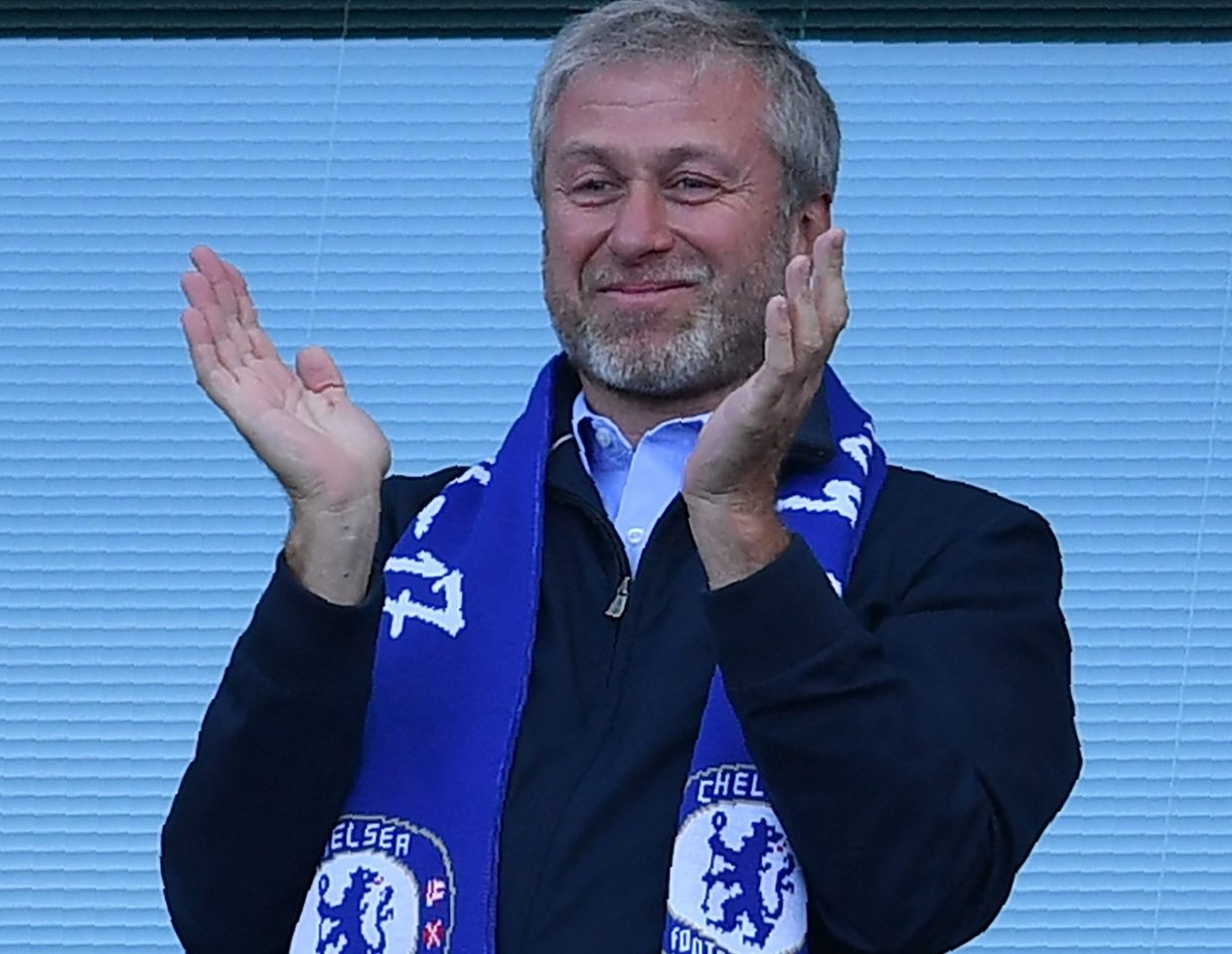

Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich arguably changed the sport completely when he swept into London to buy Chelsea in 2003, lavishing vast amounts on players and managers to bring unseen glory to the club.

Traditional powerhouses such as Manchester United, Real Madrid, Barcelona and Bayern Munich have regularly splurged massive sums on players in recent years.

But while in Abramovich’s case acquiring cultural capital may have been a consideration, Chelsea was primarily a playground to indulge his passion for the game, rather than a battleground for bigger ambitions.

Whatever the motivation for owners, UEFA’s FFP rules – however flawed – are an attempt to keep unbridled ambition within sustainable levels for the benefit of the clubs themselves; for clubs to live within their means and not face the longer-term threat of financial oblivion, should their owners abruptly pull the plug.

It is a difficult balancing act to maintain, and one that is made all the more harder when state-linked players from nations such as Qatar and the UAE step in, infusing football with political, economic and cultural agendas.

Manchester City’s rise has shown the beauty that such vast riches can bring, but also the pitfalls when football becomes a vehicle for altogether bigger ambitions.

By Liam Tyler

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.