Iraq whitewash? Swathes of UK public inquiry findings suppressed

A lack of transparency concerning a UK public inquiry into the 2003 invasion of Iraq has bred heated criticism that its findings may vindicate a brutal war that divided the nation and blackened Tony Blair’s decade-long leadership.

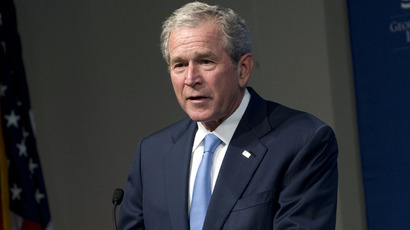

In the aftermath of the eight-year investigation, the inquiry’s concluding report has been delayed as a result of negotiations concerning its content. Of particular concern to the British establishment, are records of a series of meetings and exchanges between then-US President George W. Bush and Blair.

It first emerged the Cabinet Office and Ministry of Defence had blocked the release of these records in May 2014. Several months later, it has now been confirmed large proportions of these controversial exchanges will be omitted from the inquiry’s final report – remaining obscured from public knowledge indefinitely.

Following the conclusion of this inquiry, the investigation's chair, Sir John Chilcot, is set to issue letters to former Prime Minister Tony Blair and then-Foreign Secretary Jack Straw. Chilcot is reportedly critical of the duo with respect to the UK's invasion of Iraq, and subsequent military conduct there in the years that followed.

While Chilcot's letters may be welcomed by the British public, an overall lack of transparency relating to the report’s findings is likely to prove a disappointment for many.

Chilcot’s agreement to only release portions of the Blair-Bush exchanges could potentially jeopardize questions posed in the aftermath of the investigation’s findings. It will also be regarded by many as a retreat from a prior insistence on transparency.

At the time of the Iraq Inquiry’s enactment, then Prime Minister Gordon Brown emphasized “no British document and no British witness will be beyond the scope of the inquiry” unless it is “essential to our national security.”

But the omission of potentially crucial Bush-Blair records raises serious questions about the “legitimacy of the investigation” and reinforces a “culture of opacity in defense and security services,” according to Jameela Raymond, a defense and security expert at Transparency International (TI) UK.

Raymond claims that since the inception of TI UK’s Defence and Security Programme, the anti-corruption think tank has witnessed state opacity justified on the grounds of national security on countless occasions.

While withholding information from the public as a means of preserving national security may, at times, be necessary, Raymond insists it is often merely an “excuse to hide corruption and avoid embarrassing those who do not wish their decisions to be accountable.”

“National security is no excuse for excessive secrecy and it is a phrase that democratic governments should use only when it genuinely applies. Rather than protect us, a lack of transparency can foster insecurity at home and abroad by undermining the legitimacy of our armed forces and the decision-making process of our elected representatives,” she said on Friday.

Last week, during a select committee hearing, Sir Jeremy indicated he wanted Chilcot to publish “the maximum possible” without jeopardizing Britain’s relationship with the US and “without revealing secrets that don’t need to be revealed.”

But given the Iraq war burdened Britain with a huge financial and human cost, the full release of the Blair administration’s reasons for going ahead with the conflict is arguably in the public interest. Should state secrecy prevail in this context, Raymond insists Britain’s “leaders will not be held accountable for their actions.”

Chilcot's agreement only to release portions of the Blair-Bush exchanges could compromise the efficacy and integrity of the Iraq Inquiry.

Raymond argues those who have obstructed crucial elements of the inquiry’s findings owe the British public an explanation. But whether such a justification will surface remains to be seen.