Regrowing the heart: Scars from heart attacks cured with stem cells in pioneering study

UK scientists injected mice with stem cells for 12 weeks and saw damage from heart attacks reversed – preventing heart failure. They believe a similar procedure is possible for humans.

“This research is an early, but important, step towards understanding how we might be able to encourage stem cells in failing hearts to repair the damage caused by a heart attack,” said Professor Jeremy Pearson, Associate Medical Director at the British Heart Foundation, which provided part of the funding for the Imperial College team that conducted the study.

“A crucial next step for this research will be to establish if the human heart has similar heart-repairing stem cells to those pinpointed by this method in mice.”

READ MORE: New stem cell may eventually generate human organs in animals, save millions of lives

Heart tissue is damaged when it is deprived of blood during a myocardial infarction. Even if the patient is revived in time, the affected muscle becomes scar tissue, leaving the survivor weak, breathless and susceptible to further heart attacks, and eventually heart failure, when the organ is simply unable to pump sufficient blood to keep a person alive.

Following one of the most promising directions in medical research, the Imperial College team looked for stem cells – young cells that are able to transform into specialized cells within the body – to inject into the mice.

But not all stem cells were as effective.

READ MORE: Lab for genetic modification of human embryos just $2,000 away – report

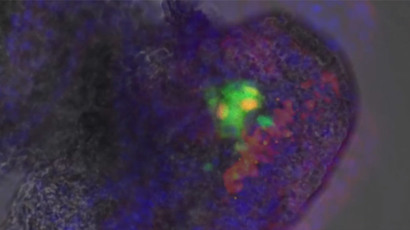

“We have found stem cells in the heart that have a specific protein – called PDGFR alpha – on their surface have the greatest potential to repair damaged hearts,” said British Heart Foundation Professor Michael Schneider, one of the authors of the study, which has been published in Nature Communications.

“When we injected stem cells with this protein into damaged hearts, we saw a significant level of heart repair. Now that we know which stem cells to use, we want to find their equivalent in human hearts for more efficient heart repair and regeneration after heart attacks.”

The potential of PDGFR alpha to heal the heart had been identified in several scientific papers in the past decade, but the next step will be more animal, and eventually, human trials.

“Future treatments could be injections of stem cells, as in our current experiments, or use of the healing proteins that these cells make,” Schneider said.

This is not the only pathway of stem cell research to repair the heart, with more than 20 different human trials currently ongoing, experimenting different types of cells and delivery methods. While some of the studies are in the final stages, none of the treatments have been approved by the US regulator FDA or the European Medicines Agency for general use as yet.

According to the World Health Organization in 2012, the latest year available, more than 7 million people died of coronary heart disease, with a large proportion of the deaths resulting from chronic illness that could be targeted by stem cell therapy.