‘There the Fyer began!’ Origin of 1666 Great Fire of London uncovered

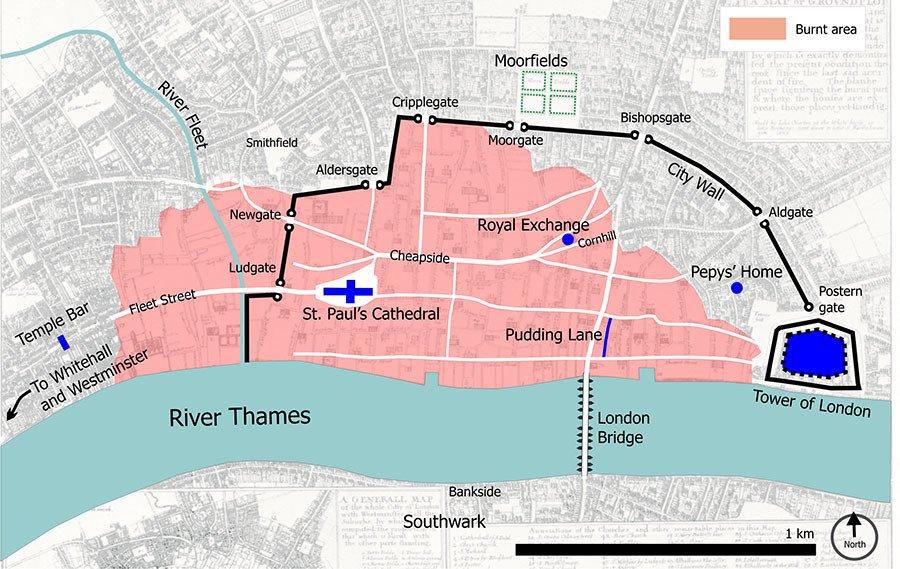

Dusty old documents uncovered by an academic reveal the true location where the Great Fire of London began. The blaze devastated London in 1666, destroying 13,200 houses and 87 churches in its path.

Although generations of school kids have been taught that the infamous fire was sparked at Thomas Farriner’s bakery in London’s Pudding Lane, the true origin of the blaze has been traced to a separate location on a nearby street.

‘There the Fyer began!’

The revelation comes some 350 years after the fire gutted London, raging through 436 aces of the city. The blaze began in the early hours of September 2, 1666, in Farriner’s bakery, where it is believed the owner left fuel a little too close to his oven. While he and his family escaped unharmed through a window, their maid lost her life in the ensuing blaze.

The precise site of Farriner’s bakery was discovered after a planning document from 1679 was uncovered in the London Metropolitan Archives. The document, which was unearthed by academic Dorian Gerhold, was an old survey with a drawing of the bakery on it. At the rear of the drawing, is a historic note that reads: “Mr Fariners grounde there the Fyer began.”

Although Pudding Lane has survived to the present day, the precise location of Farriner’s property had been lost over time. A memorial stone erected in 1680 to commemorate the Great Fire of London blamed Catholics for the catastrophe. However, it was removed circa 1750 because it attracted sightseers that tended to block the adjacent passageway.

A separate monument erected to remember the blaze known as the Doric Colum has survived to this day. The column bears an inscription that reveals the fire began 202 feet away from its foundations.

Gerhold, who researches historic buildings in London, has intrigued historians with his discovery. He managed to verify the location of the bakery by cross-referencing the plot with more contemporary maps of the district. Among these, were 1886 plans for the construction of Monument Street – a road that leads to Doric Column.

These plans, in conjunction with Gerhold’s measurements, indicate that the oven which gave birth to the Great Fire of London was situated on what is now known as Monument Street, some 60 feet east of Pudding Lane.

‘Sound evidence’

Gerhold, whose report will be published in the London and Middlesex Archeological Society Transactions journal later this year, has been commended by his peers. British historian Stephen Porter, who wrote ‘The Great Fire of London’, said the research is methodical and based on “sound evidence.”

“From this we know the location of the plot and the shape of Farriner’s property, which is good, and we now know with a reasonable degree of certainty where the fire started,” he told the Telegraph.

“This is a deft piece of research which identifies for us the location and layout of where the Great Fire began and helps us to understand the origins of the fire and how the disaster could have begun.”

Gerhold said he was unaware of his discovery’s significance at first.

“I assumed it was known. It was only later when I tried to check it that I realized that no one else knew,” he told the Telegraph.

“The site had been left empty, because there was an assumption that – like with the Twin Towers in New York – they shouldn’t build on it. Someone applied to use the land as storage, so people were sent to do a report, and that is what I found.”

In 1666, London was the most densely-populated urban settlement in the world, despite the fact over 100,000 people had been killed by the bubonic plague. The city was decidedly medieval looking, with narrow streets, closely aligned properties, darkened lanes, poor sanitation and rubbish-filled cobble stones. Water, which was largely unclean, was provided via an inefficient and complex system of elm pipes partially fed by watermills just under London Bridge.

Fire was a real and consistent fear. All but a few buildings were made of wood, often sealed using tar and roofed with thatch. Blacksmiths, glaziers, foundries and bakers all posed a risk, as did domestic fires, candles, ovens and stores of gunpowder left over from the English Civil War.