Legalize human genetic engineering to cure serious diseases, says Nobel Prize-winner

People destined to inherit serious diseases could be cured by a type of genetic engineering currently illegal in Britain, a Nobel Prize-winner says.

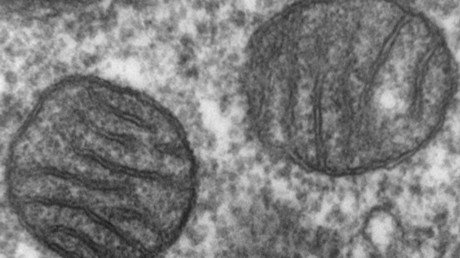

The invention of a new genome editing tool called “germline therapy” means precise changes to genetic material can be made to correct faulty DNA in human sperm, eggs and embryos.

However, the procedure is banned in Britain and many other states because the genetic changes would be passed down to future generations with largely-unknown risks.

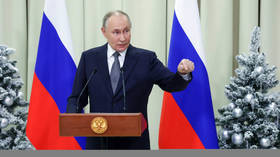

Sir Venki Ramakrishnan, speaking to the Guardian, says the risks and benefits of the procedure, which could create the first genetically-modified humans if given the green light, need to be debated.

“It’s definitely a major step, there’s no getting around that.

“What we need is a diverse and transparent group of people to really come together and get to grips with how we go about using this tool and are there red lines. They may well decide there are red lines we shouldn’t cross.

“The concern I have is the same as with any other technology, which is that once a technology is feasible, we may well regulate it but someone somewhere may start using it in ways we consider unethical.”

At a meeting in Washington, DC, in December, scientists decided not to impose their own global ban on modifying human embryos destined to become people but stated that to do so would be unacceptable given the unknown risks today.

‘GM crops shouldn’t be banned’

Meanwhile, the Royal Society, of which Ramakrishnan is president, will publish a report on Tuesday about genetically modified crops.

According to the report, half of the UK population does not feel well-informed about GM crops, and a further 6 percent have never heard of them.

Crops that are modified to resist pests, grow in harsh conditions and contain more nutrients may become increasingly important as the world’s population grows, Ramakrishnan says.

“We wanted to provide the background and facts about some of the most important questions people have on GM crops.

“If we have better tools at our disposal, should we use them or not? It’s a question society has to decide.”

In 2015, GM crops were grown in 28 countries and on 180 million hectares - the equivalent of seven times the land area of the UK.

But in the same year, more than half of the EU officially banned farmers from growing GM crops, including Germany, France, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The bans were imposed despite EU regulators finding GM crops pose no risk to health or the environment.

Ramakrishnan argues crops should not be judged on whether they are GM or not.

“GM as a technique is no more dangerous than any other agricultural technique. What most scientists believe is that any new crop we introduce needs to be tested on a case-by-case basis according to its traits, not how it was reproduced.”

Among the concerns about GM raised by environmental groups and NGOs is the risk that large companies may monopolize agriculture and wield too much power over growers.

“I can understand how a backlash happened against GM. But the solution is not to ban GM, it’s to take it out of the hands of a few corporations,” Ramakrishnan says.