Chilcot’s forgotten witnesses – Britain’s Iraqi diaspora (VIDEO)

The 2003 Iraq invasion and occupation left at least 500,000 dead, scattered refugees to the wind and threw the region into chaos. Yet as Sir John Chilcot delivers his long-delayed Iraq Inquiry report, the silence of Iraqis themselves is deafening.

“If the United Nations said themselves Iraq can’t import enriched baby powder milk, ambulances and tampons, how was Iraq going to pose a threat to the sovereignty of the United Kingdom?” asks Hussein Al-alak, the Manchester-based editor of Iraq Solidarity News (Al-Thawra).

Hussein isn’t alone in doubting Tony Blair’s case for war, based as it was on claims of an imminent threat to the realm posed by Iraq’s elusive weapons of mass destruction (WMDs).

Launched in 2009 to examine the road to war, the invasion and its aftermath, the 2.6 million-word Chilcot report has cost the UK taxpayer roughly £10 million (US$13 million).

Shedding light on how British foreign policy blundered into the war, and with the intention of stopping similar misadventures being repeated (Libya excluded), Sir John’s report may also issue some kind of verdict on the invasion’s legality.

If the families of the 179 servicemen and women killed in Iraq appear skeptical about finding closure in Chilcot’s tome, Britain’s tens of thousands of Iraqi exiles must be utterly incredulous at their own apparent exclusion in this official history of their nation’s tragedy.

Ahead of the July 6 publication, RT reached out to Britain’s Iraqi diaspora to hear their views on the war and expectations of the report.

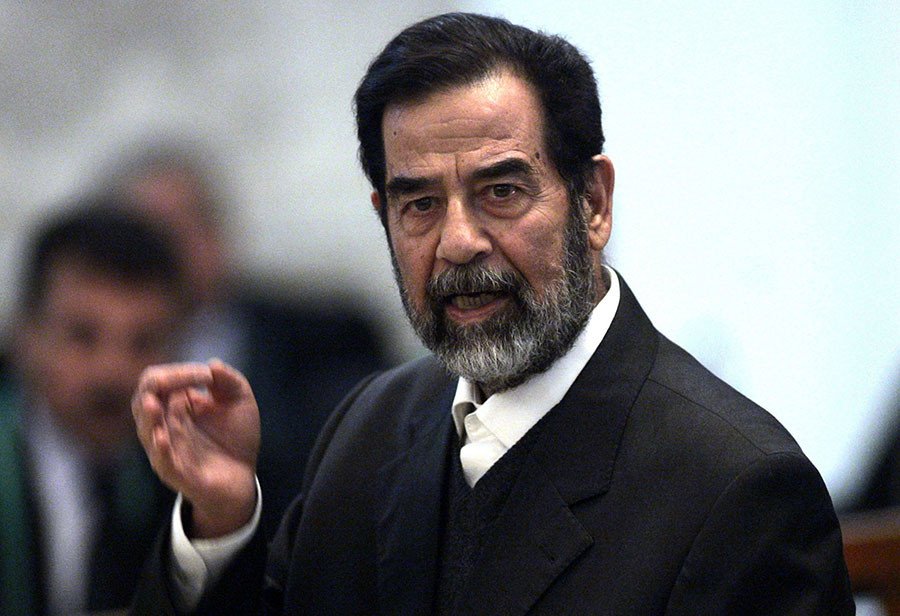

“Saddam [Hussein], in my opinion, is a system that will never be repeated in history. It’s a state of fear,” says Emad Al-Ebadi, Director of the Iraqi Welfare Association (IWA), based in Wembley, north London. Emad says he came to the UK in the late 1970s as a student. His family urged him not to return to Iraq, however, as the vicious and protracted war with Iran took hold.

He is among a generation of Iraqis who were unable to return to Saddam’s Iraq, fleeing war, sanctions and persecution. As a Shia Muslim, Emad’s community faced particular cruelty under the regime.

Asked whether it was therefore right for Britain and America to topple Saddam in 2003, Emad laments the price Iraqis have paid for their so-called liberation.

“This is a question I’ve been asked many times. It’s very difficult a question, because yes the intervention was needed, because there was no other way of getting rid of that man. [But] the way it was done, we don’t agree with it. We paid a high price, and we’re still paying a high price. For several reasons.

“I think the first thing, the West is not genuine. It is not about human rights and Iraqis and things like that. They didn’t do it for that reason. America did it because they are a cowboy state.

“The British, Tony Blair and that lot, they’re a puppet to the Americans. Whatever they order them to do they agree to it and they do it.”

Shia Iraqis like Emad are not the only ethnic group to suffer under Saddam.

Miran Hassan, Director of the Kurdish Culture Centre (KCC) based in Kennington, south London, came to the UK in 1999 as a child refugee with his mother. His father was a conscript in the Iraqi Army who fled to Italy. Any Kurd who dodged conscription under the Saddam regime risked execution and their families were made to suffer. Sanctuary therefore was sought in Britain.

Measuring Saddam’s ruthlessness on body count alone, Miran compares the crimes of Islamic State (IS, formerly ISIS/ISIL) to the Baathist slaughter of Kurds.

“If my numbers are correct, ISIS, during 2015, killed just over 2,000 people in Syria. Saddam in a matter of minutes killed 6,000 Kurds from the largest chemical attack in history, in Halabja.

“Over the period of the Anfal campaign he killed nearly 200,000 Kurds … We’re still digging up mass graves to this day because of Saddam.”

Miran takes a harder line in support of the West’s removal of Saddam, but his tone betrays a deep sense of bitterness at the perceived abandonment of Kurdish and Shia rebels fighting the Baathists in 1991 at Washington’s behest.

“I think it was definitely right to topple Saddam and intervene. However, I think it was done too late. It should have been done in ‘91. The First Gulf War. That was when the people were rising up all over Iraq, because of what George Bush Sr. said – rise up against the regime. We did that. The Shias did that. The Kurds did that. Every oppressed people in Iraq did that. However, the betrayal we received led to the regime solidifying their grip over Iraq.”

Hussein Al-alak is less forgiving of the British-American intervention. The Iraq Solidarity News (Al-Thawra) editor, whose mother is British and father Iraqi, believes the invasion opened a Pandora’s Box of sectarianism and ripened the conditions for the rise of Islamic State.

“Was it right for Britain and America to remove Saddam Hussein? No, it was not. And that is from a kind of policy perspective, because what we now have seen is an Iranian controlled regime, what we have seen is sectarianism on a scale that’s never existed inside of Iraq … and what we’ve also seen now is the destruction of the Iraqi state as a 21st century state apparatus.

“I would go so far as to say there was no post-war planning inside of Iraq from either Britain or America … When you invade a country, the first thing you don’t do is disband the state, you do not tell the army and you do not tell the police force that you’re all out of jobs. You don’t go and tell 24 million people that because you’ve lived under a one party state for 35 years that you’re all being made redundant, you don’t have jobs to go to and that we are the ones now in charge.

“When you go into a country and you impose that type of regime, which Britain and America did after 2003, you galvanize an entire country against you and it ends up in violence and chaos.”

Does bad planning constitute a war crime? Emad believes Britain and America’s culpability runs deeper than the mere failure to plan effectively for a post-Baathist era. For him, ‘shock and awe’ and ‘mission accomplished’ are bywords for state terrorism, perpetrated against the Iraqi people. Asked whether Chilcot is likely to draw the same conclusions, Emad holds out little hope for justice.

“I do not expect any benefit to Iraq, that’s certain,” Emad shrugs. “I don’t expect anyone will be prosecuted. I don’t think there will be any confirmation of war crimes. I mean, it is a war crime when you go and bomb a country, whatever it is, wherever it is. It’s a war crime. It’s state terrorism.

“When you send airplanes, and we all watch it live on TV, it’s like Star Wars films. We’ve seen it live, this is our people we talk about. We’re not talking about films in Hollywood. I was watching all night this bombing of innocent people … They come back very happy [saying] they accomplished their mission. What’s the mission? Killing innocent people … But there is no justice in the world. Who’s going to punish them? The United Nations?”

Hussein is less emotive in his appraisal, but no less scathing. In his view, unless convincing evidence of weapons of mass destruction is presented, and the 45-minute threat touted by Blair substantiated, Britain’s war on Iraq can be reasonably considered a war of aggression.

“The first question one needs to ask if the situation in Iraq was carried out either legally or illegally is did it have a UN mandate? No, it did not. Secondly … was it a war of aggression or a war of defense? If it’s a war of aggression, that means Britain acted as the aggressor, therefore the actions were unprovoked. If it was a war of defense, it means Britain felt threatened and Iraq posed an immediate threat to the sovereignty and the integrity of the United Kingdom.

“We were told there were weapons of mass destruction that could be set off in 45 minutes. Iraq under the sanctions was not allowed to import bleach, it wasn’t allowed to import pencils because pencils contained graphite. It wasn’t allowed to import pipelines to facilitate the flow of water. So if Iraq wasn’t able to import three items like that … how was Iraq going to pose a threat to the sovereignty of the United Kingdom?”

Even if Chilcot fails to identify anything legally constituting a war crime, in which case it will be widely considered a whitewash, will Britain at the very least draw lessons from the Iraq debacle? Miran says history has a nasty habit of repeating itself.

“Are we really going to get closure out of a report, over a decade later? When we’re still making the same mistakes in the region? We’re treating every problem the same. There’s a saying: if all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. And that is exactly what we’re seeing right now. So I do hope we learn from the report. But do I think we will? I don’t think so.”

Decades of war have built a level of emotional resilience among Iraqis that is hard for British observers to fathom. Emad is hopeful that a new generation of Iraqi millennials is emerging with a renewed commitment to a united national identity. He therefore saves his final thoughts for the architects of British and American foreign policy.

“I would say, the Western powers should not interfere in ‘Third World’ countries’ politics … If that is stopped, we, everyone, will live on a better, peaceful planet.”