Britain’s forgotten prisoners: 4,000 people trapped behind bars in ‘never-ending’ IPP limbo

Twelve years into a three-year jail term, Ian Hartley is languishing behind bars indefinitely. With no release date, he is one of almost 4,000 prisoners in Britain serving a tortuous indeterminate sentence.

Hartley, 44, was sentenced in 2005 for robbery under the controversial imprisonment for public protection (IPP) program. Despite serving four times his sentence, and the scheme being abolished five years ago, there is no release date in sight.

“It would be more humane to give them the death penalty - at least they will know there’s an end,” Hartley’s partner Joanne Hibbert told RT.

“It is mental torture. It’s the not knowing. The government wants it to be forgotten about - and it is being forgotten about.”

IPPs were introduced in 2005 under former Labour Home Secretary David Blunkett. They were designed to protect society from dangerous, violent, and sexual offenders whose crimes were not deemed serious enough to warrant a life sentence but who posed a “significant risk.”

The sentence was applied far more widely than envisaged, however, swelling the prison population to unprecedented levels and putting huge pressure on the already stretched parole board.

Rather than targeting dangerous criminals – with an expected rise in the prison population of 900 – the sentence was handed down to 8,711 offenders between 2005 and 2012. They included arsonists, pub brawlers, and street muggers.

In 2012, IPP was abolished under the Coalition government after a European Court ruling claimed it was “arbitrary and unlawful.” Former Justice Secretary Kenneth Clarke agreed, labeling it a “stain” on Britain’s criminal justice system.

Its abolition was not retrospective, however, meaning there are still almost 3,989 prisoners – or five percent of the prison population – serving sentences without a release date, according to campaign group Smash IPP.

The scheme costs British taxpayers approximately £131 million every year, and the sanity of those inside. IPP prisoners suffer from alarmingly high levels of suicide and self harm.

Hartley recently penned an open letter describing his life in prison.

“Nobody knows what this environment is like unless you live or work here, no wonder people are killing themselves, cutting themselves, or drugging themselves up,” he wrote.

“I might be headstrong … but I honestly don’t know how long I can keep going like this, I need emotion, love, compassion. I get that every week on a visit that’s it, the rest is dark and scary … slashings every other day, people beat with table legs, broom handles, stabbings - it’s no holds barred.”

Hartley will next appear before a parole board in November.

‘There’s no light at the end of the tunnel’

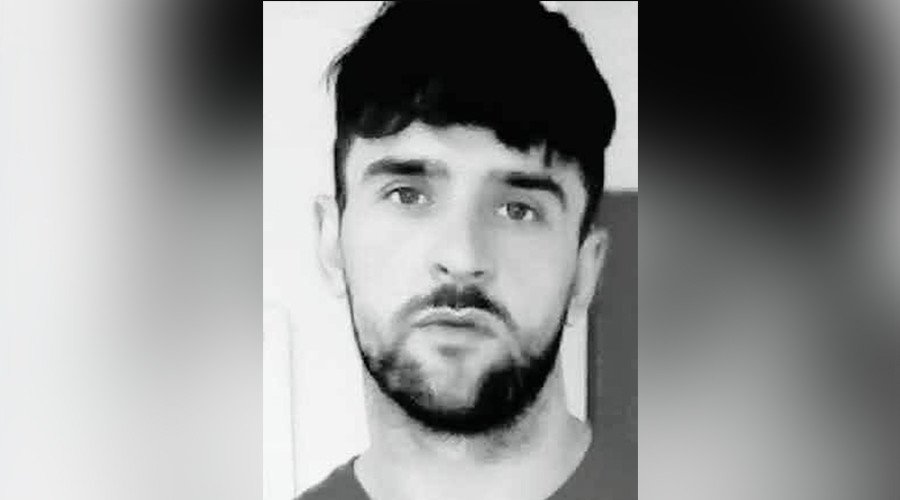

Joshua Mcrae, 27, is eleven years into a four-year jail term for ‘wounding.’

Mcrae’s partner Racheal Franklin told RT he is struggling to cope. Without a release date to look forward to and a future to plan, there is “no light at the end of the tunnel,” she says.

“It is this constant never knowing.Every year you build up your hopes thinking maybe this year, maybe this year, and then your hopes are dashed. Then you get to the point where you don’t have any hope left.

"That’s why you see IPP prisoners self harming, high suicide rates – because they just don’t have any hope.”

Franklin says if Mcrae had been handed down a normal sentence, he would have already been released without any problems. She questions why sex offenders and murderers who serve their time are released, but IPP prisoners in jail for more minor offences are left waiting.

“We are not expecting them to release 4,000 prisoners tomorrow – that’s just not realistic. We are asking them to look at their sentences and make them mandatory. Then they can serve their sentences, give themselves a time period, and be released with proper plans so that they are managed in the community.”

Franklin says Mcrae, who has shared cells without issue and never harmed another prisoner, has been denied the ability to demonstrate that he is not a risk to the public.

His Offender Assessment System (OASys) report, which measures the risks of criminal offenders on release, is 18 months out of date, he is regularly transferred between prisons so he cannot build relationships with prison officers, and the supervisor who is supposed to meet with him regularly to discuss sentencing plans has spoken to McCrae just once by video link in four years, Franklin says.

“Every time he goes to the parole board and they ask what he has done to prove he is not a risk to the public, he says: ‘Well, what can I do? The professionals who are supposed to be helping me with a sentence plan are not – I don’t have access to those resources.’

“He’s going in front of a parole board and it’s almost like he’s being set up to fail before he even starts the process,” Franklin says.

McCrae will next appear before the parole board on October 5.

Last month, the chair of the parole board, Nick Hardwick, expressed his frustration at the government’s failure to “get a grip” on IPP. He described them as a “blot” on the system when he was appointed to the board almost a year ago.

The Ministry of Justice replied saying it is processing cases as quickly as possible.