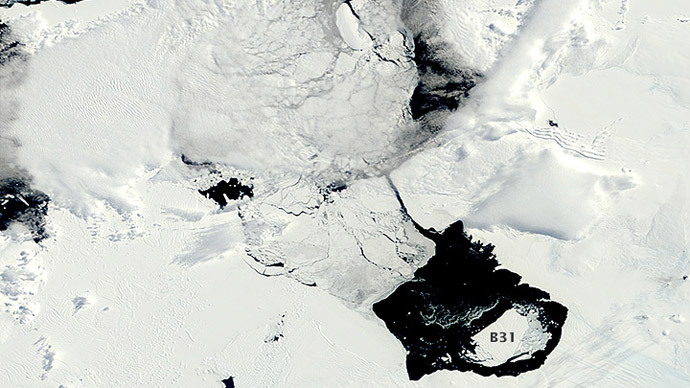

Dubbed “B31,” the iceberg could pose some significant problems for ships if it continues to melt or break apart in the Southern Ocean.

At 255 square miles (660 sq. km) and 500 meters thick, B31 is one of the biggest icebergs on the planet – and currently six times the size of Manhattan.

Although the process of icebergs breaking off from glaciers is typical – “iceberg calving,” as its known, typically occurs at the Pine Island Glacier every six to 10 years – NASA’s Earth Observatory is attempting to keep a special eye on B31.

“Iceberg calving is a very normal process,” NASA glaciologist Kelly Brunt said on the agency’s website. “However, the detachment rift, or crack, that created this iceberg was well upstream of the 30-year average calving front of Pine Island Glacier (PIG), so this a region that warrants monitoring.”

Currently, B31 is not in the way of any Antarctic shipping lanes, but Brunt said its current trajectory means that's where the iceberg is headed.

"It's floating off into the sea and will get caught up in the current and flow around the Antarctica continent where there are ships," she said, according to the Guardian.

NASA has been monitoring the Pine Island Glacier since 2011, when it first observed a crack that eventually got larger and resulted in B31 breaking off into the ocean. The massive glacier has been highlighted by scientists over the last 20 years due to the fact that, as NASA put it, “it has been thinning and draining rapidly and may be one of the largest contributors to sea level rise.”

As noted by the Guardian, Kelly said this iceberg alone wouldn’t contribute significantly to rising ocean levels even if it melted completely. However, should the Pine Island Glacier continue shrinking in size, it could raise global sea levels by 1.5 meters.

Despite the increased interest by NASA, the agency said keeping track of B31’s movement over the next six months will be difficult, since winter is descending on the region and it will be blanketed in darkness.

“We are doing some research on local ocean currents to try to explain the motion properly. It has been surprising how there have been periods of almost no motion, interspersed with rapid flow,” University of Sheffield researcher Grant Bigg told the Earth Observatory.

“The iceberg is now well out of Pine Island Bay and will soon join the more general flow in the Southern Ocean, which could be east or west in this region.”