How safe is your money? US Treasury says it limits spy access to bank books

While not denying that it allows US intelligence agencies sneak peeks at “suspicious” money transactions by its clients, including those by Americans, the Treasury Department said it sets limits on what the spies may view.

In response to a freedom of information request, the Treasury

released information as to how it allows the National

Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), the primary organization of the

US government for analyzing intelligence on terrorism, to examine

reports that banks create on suspicious or large cash

transactions made by customers.

The partially redacted document, reported by Bloomberg, also

established conditions for intelligence agencies conducting

searches on the Treasury’s database.

“Financial data can be some of the most relevant as to how

people are connected,” NCTC director Matthew Olsen told

Bloomberg. “That’s why it’s vital that we have access”

to the FinCEN database, he said.

US banks keep records on more than 15 million currency

transaction reports annually on the movement of $10,000 or more

into or out of an account, according to FinCEN, a department that

falls under the US Treasury’s Office of Terrorism and Financial

Intelligence (TFI). Meanwhile, financial institutions such as

banks, brokerages and even casinos, file more than 1.5 million

suspicious activity reports each year.

Although the NCTC tracks travel habits, communication records and

other relevant information when investigating possible terrorist

activity, following the money is of primary importance, and has

been used to trace financial moves from people in the US to

terrorist organizations in Yemen or Syria, Olsen said.

“Financial connections are the most binding between

people,” he added. “When we can find connections based

on money, it’s not a smoking-gun piece, but it helps with

analysis.”

Since the terrorist attacks of 9/11, which seemed to fast-track a

huge intelligence foray into the lives of private citizens, many

people have become increasingly concerned as to what sort of

information is being collected on them in the name of security.

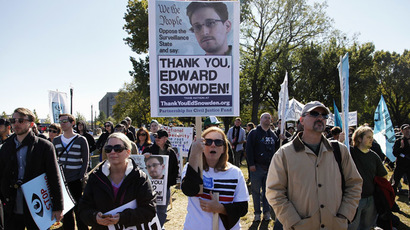

Last summer, Edward Snowden, a former NSA

contractor-turned-whistleblower, blew the cover on America’s

worldwide data-collection program, which exposed the Obama

administration to harsh global criticism. Since then, Washington

has been attempting to assure US citizens and foreign allies that

the United States is not the Orwellian nightmare some say it has

become.

10 things we didn’t know before Snowden

A 2010 memorandum of understanding between the Treasury’s

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and the NCTC

attempted to address those suspicions by requiring that the spy

agencies strive to retrieve data that pertains only to specific

cases and immediately destroy data obtained “in error.”

“The data we collect is publicly known,” FinCEN Director

Jennifer Shasky Calvery told the news agency. “It’s not raw

data. It’s suspicious, large-cash transactions that meet a

threshold.”

“We think we’ve gotten that balance right, although it is

something we must always be ready to re-examine.”

Last month, European MEPs voted by 544 to 78 in favor of putting on hold many joint EU-US programs, including

one dubbed SWIFT, a financial-record sharing program designed to

track terrorist activity.

The Snowden leaks showed the NSA gained a “back door” entrance

into the SWIFT servers, which revealed the banking details of

millions of European citizens, despite the fact that access to

these financial data had been strictly limited by the Terrorist

Finance Tracking Program (TFTP).