Fire and Forget: DARPA successfully tests revolutionary self-guiding bullet (VIDEO)

US military research agency DARPA says it is homing in on its long-term ambition of producing self-guided bullets, after staging a test in which a sniper was able to shoot at a target at a radically wrong angle, and yet still hit it perfectly.

“DARPA’s Extreme Accuracy Tasked Ordnance (EXACTO) program

recently conducted the first successful live-fire tests

demonstrating in-flight guidance of .50-caliber bullets,”

said the organization, which posted a recording of the trial on

YouTube.

“This video shows EXACTO rounds maneuvering in flight to hit

targets that are offset from where the sniper rifle is aimed.

EXACTO’s specially designed ammunition and real-time optical

guidance system help track and direct projectiles to their

targets by compensating for weather, wind, target movement and

other factors that could impede successful hits.”

But behind the dry description is a fascinating use of technology

that the Pentagon has invested more than $25 million into since

the program’s inception in 2008.

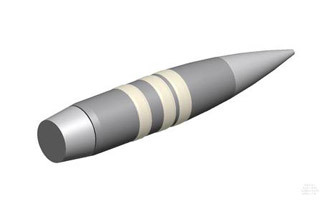

While the exact technologies used remain classified, an automatic

aiming rifle consists of two parts – a guidance system and the

bullet. The first tracks the target, meaning that the sniper

simply has to “see” it with a with a sophisticated optical sight,

and send signals to the bullet. With a number of fins and an

on-board computer, the bullet – which may also calculate air

pressure – constantly re-adjusts its path to home in on the

target. To make rapid fire even simpler, it may simply react to

any heat or movement near the target area, in what is known as

“fire-and-forget.”

In 2012 another government researcher, Sandia National Labs,

tested its own guided bullet, and claimed similar accuracy and

distance results for it, though it uses a laser beam for

targeting – which could make it less useful in smoky or foggy

weather conditions, as well as being easier to spot for the

enemy.

Currently, US Army snipers are expected to hit a target 600

meters away, nine times out of ten. But after a certain point,

about a kilometer away, accuracy falls off sharply, even in

perfect conditions. Besides, current technology simply does not

allow snipers to easily estimate the impact of humidity and

cross-winds on the bullet trajectory, meaning that even the best

will often have to fire several bullets before they even get

close – ruining the surprise factor, and placing themselves in

danger of return fire. EXACTO promises a range of up to 2,000

meters, as well as a virtual indifference to conditions.

And the US Army is genuinely relying on this project.

As its tactics have evolved from head-on combat to tactical

missions against small groups of insurgents in treacherous

terrain – in which loss of American lives must be minimized – so

the number of snipers has risen. According to Time magazine,

there were 250 in the entire army before the Iraq war, and that

number more than trebled at the peak of the simultaneous US

operations abroad. While overall military capacity may decrease

in the coming years, with the Obama administration keen to avoid

being trapped in unwinnable regional conflicts, the role that

snipers will play will only grow.

While the success of the DARPA program may fill the corridors of

the Pentagon with cheer, as with any improvement that increases

the potency of easily-available weapons (EXACTO could even be

fitted onto an ordinary rifle), it has its own risks. The US Army

is not likely to make EXACTO available to civilians, but the

technology will filter down and spread abroad, and Sandia

National Labs has already announced that it plans to make its

system commercially available. And while military innovation is

necessary, the US will no doubt be worried about seeing rifles

that can hit from 2km away, wielded by untrained foreign

militants and disturbed American gunmen in the near future.