New York Times finally begins describing CIA interrogation tactics as 'torture'

In the more than ten years since the CIA’s interrogation tactics began coming to light, many members of the mainstream media refused to describe them as torture. On Friday, the New York Times announced they will begin using the word.

The about-face by the Grey Lady comes a week after President Barack Obama made a rare acknowledgment during a press briefing concerning the United States’ past use of enhanced interrogation tactics in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks.

“In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, we did some things that were wrong. We did a whole lot of things that were right, but we tortured some folks. We did things that were contrary to our values,” Obama said near the end of a nearly hour-long press briefing at the White House in Washington, DC.

But even before the president’s admission, the venerable Times had begun the debate over using the word in their publications.

“When the first revelations emerged a decade ago, the situation was murky. The details about what the Central Intelligence Agency did in its interrogation rooms were vague. The word ‘torture’ had a specialized legal meaning as well as a plain-English one,” New York Times’ executive editor Dean Baquet wrote in the Times Insider section.

“While the methods set off a national debate, the Justice Department insisted that the techniques did not rise to the legal definition of ‘torture’,” Baquet continued. “The Times described what we knew of the program but avoided a label that was still in dispute, instead using terms like harsh or brutal interrogation methods.”

New York’s historic newspaper was not the only member of the mainstream media that refused to use the word torture since details of the CIA program began trickling out, according to the Huffington Post, who noted that Reuters referred to the tactics as "brutal interrogation methods" and the Associated Press called them "enhanced interrogation techniques."

While the agency’s torture program started under President George W. Bush after the September 11 terrorist attacks on the US and ended during his administration as well, the CIA’s tactics have been at the forefront of the national conversation over the last few months.

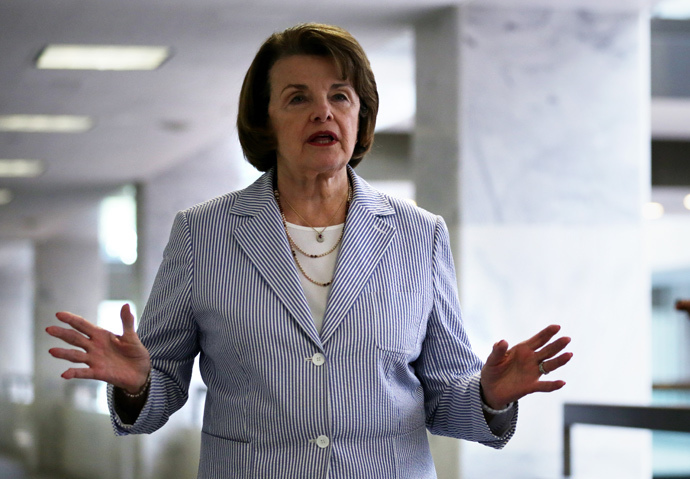

In March, the US Department of Justice announced it was investigating the CIA over alleged malfeasance at the spy agency over how it dealt with the Senate Intelligence Committee ‒ its congressional watchdog ‒ stemming from a classified report on the agency’s interrogation of terror suspects. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), the chair of the committee, claimed that the CIA was secretly monitoring her staff while they worked on the torture report, and said she had "grave concerns that the CIA's search may well have violated the separation of powers principles embodied in the US Constitution.”

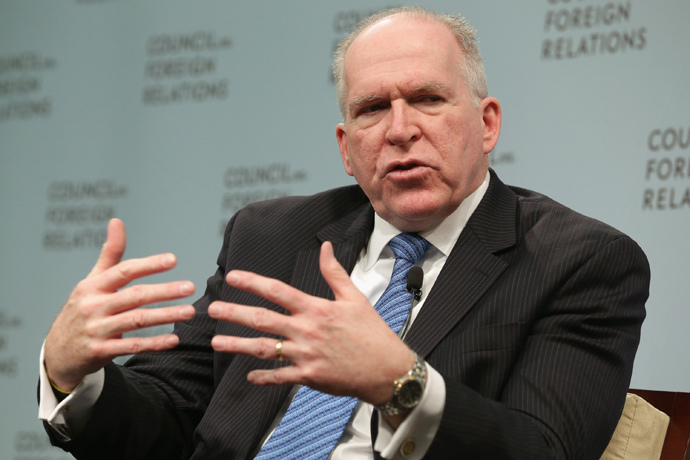

Feinstein’s accusations led the CIA’s Inspector General to ask for the DOJ inquiry, and set off a bitter feud between the Senate and the spy group. At the end of July, CIA director John Brennan admitted that some of his employees had spied on the Senate Intelligence Committee, and apologized privately to lawmakers, saying those members of his agency “acted in a manner inconsistent with the common understanding” between his body and the Senate.

The Times’ coverage of that dispute led the paper’s reporters and editors to review the issue, Baquet wrote, as did the revelations of what techniques the CIA actually employed during their 'enhanced interrogations'.

“The CIA inflicted the suffocation technique called waterboarding 183 times on a single detainee,” the executive editor said, “And... other techniques, such as locking a prisoner in a claustrophobic box, prolonged sleep deprivation and shackling people’s bodies into painful positions, were routinely employed in an effort to break their wills to resist interrogation.”

The op-ed also discusses the Justice Department’s decision ‒ under both post-9/11 presidential administrations ‒ not to prosecute people involved in the CIA’s interrogation program, which Baquet said meant that the legal definition of 'torture' became secondary to the plain-English one.

“Given those changes, reporters urged that The Times recalibrate its language. I agreed. So from now on, The Times will use the word ‘torture’ to describe incidents in which we know for sure that interrogators inflicted pain on a prisoner in an effort to get information,” Baquet concluded.