Diabetes breakthrough: Human stem cells altered to make insulin

In what could be a major breakthrough for diabetes treatment, scientists have discovered a way to drastically alter human embryonic stem cells, transforming them into cells that produce and release insulin.

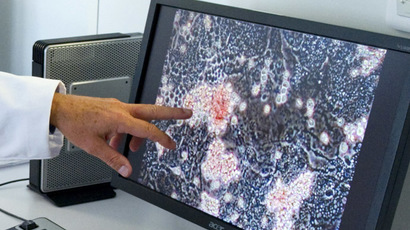

Developed by researchers at Harvard University, the innovative new technique involves essentially recreating the formation process of beta cells, which are located in the pancreas and secrete insulin. By stimulating certain genes in a certain order, the Boston Globe reports that scientists were able to charm embryonic stem cells – and even altered skin cells – into becoming beta cells.

The whole process took 15 years of work, but now lead researcher Doug Melton says the team can create hundreds of millions of these makeshift beta cells, and they’re hoping to transplant them into humans starting in the next few years.

"We are reporting the ability to make hundreds of millions of cells — the cell that can read the amount of sugar in the blood which appears following a meal and then squirts out or secretes just the right amount of insulin," Melton told NPR.

There are 29.1 million people in the United States believed to have diabetes, according to statistics by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dating back to 2012. That’s 9.3 percent of the entire population.

Currently, diabetes patients must rely on insulin shots to keep their blood-sugar levels stable, a process that involves continual monitoring and attentiveness. Failure to efficiently control these levels can cause some patients to go blind, suffer from nerve damage and heart attacks, and even lose limbs. If Melton’s beta cell creation process can be successfully applied to humans, it could eliminate the need for such constant check-ups, since the cells would be doing all the monitoring.

Already, there are positive signs moving forward: the transplanted cells have worked wonders on mice, quickly stabilizing their insulin levels.

"We can cure their diabetes right away — in less than 10 days," Melton said to NPR. "This finding provides a kind of unprecedented cell source that could be used for cell transplantation therapy in diabetes."

With mice successfully treated, the team is now working with a scientist in Chicago to put cells into primates, the Globe reported.

Even so, significant obstacles remain, particularly for those who have Type 1 diabetes. With this particular form of the disease, the human immune system actually targets and destroys insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, so Melton’s team is looking into encasing cells inside of a protective shell in order to ensure their safety.

Another hurdle is political, since many are against tinkering with human embryonic stem cells on the grounds that research wipes out human embryos. As a result, scientists are also trying to recreate their work on other types of stem cells.

Regardless, the research – formally published in the Cell journal this week – is being welcomed with open arms.

"It's a huge landmark paper. I would say it's bigger than the discovery of insulin," Jose Olberholzer, a professor of bioengineering at the University of Illinois, told NPR. "The discovery of insulin was important and certainly saved millions of people, but it just allowed patients to survive but not really to have a normal life. The finding of Doug Melton would really allow to offer them really something what I would call a functional cure. You know, they really wouldn't feel anymore being diabetic if they got a transplant with those kind of cells."