90% of Americans are poorer today than in 1987

The American Dream is slipping further away from the vast majority of Americans than it has in a quarter century. Now 90 percent of US households are poorer than they were in 1987, according to both a new study and the head of the Federal Reserve.

“The new, harsh reality is that the bottom 90 percent of households are poorer today than they were in 1987,” Matt O’Brien wrote in the Washington Post Wonkblog, citing data from a new National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) paper on U.S. wealth inequality, which he says is based on tax data. “It's been a lost 25 years for the bottom 90 percent, but a lost 15 for the next 9 percent, too. That's right: altogether, the bottom 99 percent are worth less today than they were in 1998.”

Federal Reserve Board Chairwoman Janet Yellen delved deeper into the statistics at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Economic Conference on Inequality of Economic Opportunity last Friday.

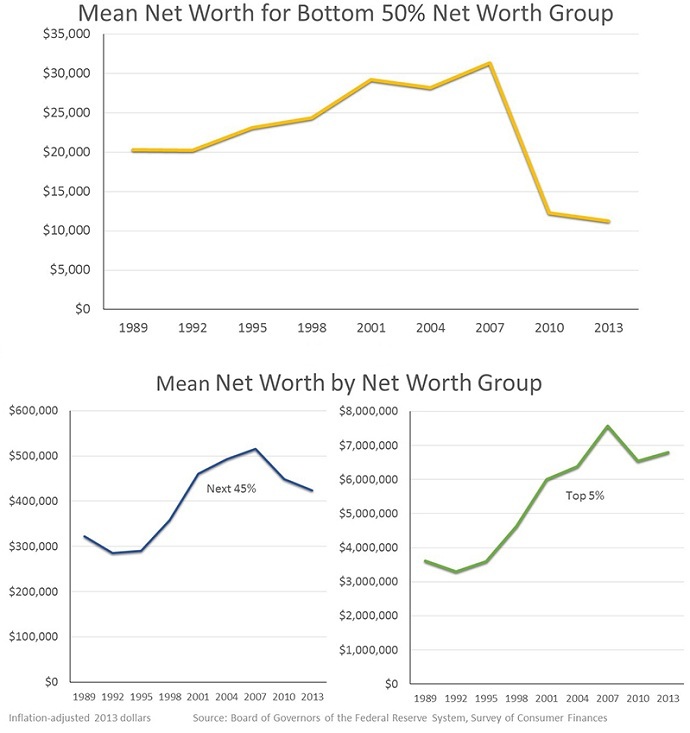

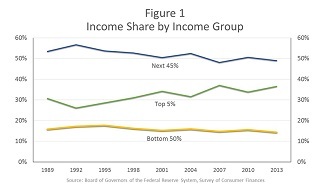

“The wealthiest five percent of American households held 54 percent of all wealth reported in the 1989 survey. Their share rose to 61 percent in 2010 and reached 63 percent in 2013,” she said. “By contrast, the rest of those in the top half of the wealth distribution ‒ families that in 2013 had a net worth between $81,000 and $1.9 million ‒ held 43 percent of wealth in 1989 and only 36 percent in 2013.”

“The extent and continuing increase in inequality in the United States greatly concern me,” she noted. “I think it is appropriate to ask whether this trend is compatible with values rooted in our nation’s history, among them the high value Americans have traditionally placed on equality of opportunity.”

Karim Basta, chief economist at III Associates, praised the speech for focusing on a non-traditional topic for a Fed chair ‒ namely the outlook for the US economy or interest rates.

“I think she broke new ground in terms of a Fed chair looking at such a serious socioeconomic issue with that degree of rigor,” the investment adviser, who attended the conference, told the Wall Street Journal.

Both Yellen and O’Brien noted that the recovery from the Great Recession of 2008 hasn’t fully reached the majority of Americans, at least not the way it has for the wealthiest 10 percent.

Stocks collapsed during the crisis, but came back soon thereafter, but members of the middle class were in debt from buying houses, not stocks, when the markets for both crashed. And housing prices haven’t rebounded.

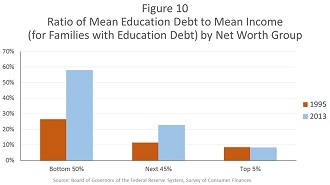

“The middle class, in other words, missed out on the big bull market in stocks, but not on the even bigger bear one in housing. That's why the recovery has restored so little of the wealth that the recession destroyed,” O’Brien wrote. “In fact, the bottom 90 percent have actually kept losing net worth the past few years, in large part, due to rising student loan debt.”

Yellen also focused on education debt as part of the problem.

“Rising college costs, the greater numbers of students pursuing higher education, and the recent trends in income and wealth have led to a dramatic increase in student loan debt. Outstanding student loan debt quadrupled from $260 billion in 2004 to $1.1 trillion this year,” she noted. “The relative burden of education debt has long been higher for families with lower net worth, and that this disparity has grown much wider in the past couple decades.”

While things are bad, they could still be worse. A recent report from Credit Suisse found that the US ranked in seventh place when it comes to wealth inequality around the world, with 74.6 percent of its wealth held by the top 10 percent, just behind Thailand, with 75 percent. Russia is the most unequal country, with the 84.8 percent of its national wealth held by its top 10 percent, CNBC reported.

And historically it’s also been worse in the United States. The top one percent now own over 41 percent of all the wealth in the country, which is the most since 1939. But O’Brien noted that “it's still well below the all-time high of 51 percent set in 1928... In other words, this new Gilded Age might get even more Gilded.”

Tim Worstall, however, argued that no one knows if wealth inequality is actually rising or falling. Every report citing statistics “absolutely every single commentary and research paper,” he wrote for Forbes, “is telling us only about marketable, financial wealth–property, private pensions, stocks, bonds and shares and so on. And it’s not particularly evident that that’s the majority of the wealth in our societies, or even the most important part of it.”

He gave an example of a fireman with a $150,000-a-year pension. Under the NBER paper’s definition of wealth ‒ because the annuity is funded from the employer’s current operating expenses (which he notes is not an unusual circumstance) ‒ that fireman “is defined as having no wealth,” Worstall noted.

“So now we’re actually ignoring the entire effect of the totality of the welfare state? This is getting worse, isn’t it? For the real point that they make in this paper is that wealth inequality is getting back to what it was before WWI. When, you might recall, there was no welfare state at all,” the Forbes contributor wrote. “And we deliberately went out and created that welfare state in order to deal with the effects of income and wealth inequality.”

Yet Worstall ignores what the Credit Suisse report focused on: that the increasing consolidation of wealth in the hands of a very few ‒ just 0.7 percent of the world’s population ‒ is a “worrying signal” that the world could be on the brink of a new catastrophic economic failure, similar to that of 2008.