Doctors use HIV to cure Utah man's leukemia

A Utah man’s leukemia is in remission, thanks to an experimental therapy. Doctors injected him with HIV-infused white blood cells, which were programmed to recognize, target and kill the cancer.

Marshall Jensen was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in early 2012. He then began searching for a treatment that would force the aggressive and often deadly blood cancer into remission. After traveling the country for unsuccessful surgeries, treatments and procedures, he learned about researchers at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where they’ve spent two decades developing a breakthrough experimental treatment that kills cancer in otherwise incurable leukemia patients, KSL reported.

"It felt right; and we didn't know how we were going to get out there, what we were going to do, but it worked,” Jensen said. “By God's grace I was able to come back."

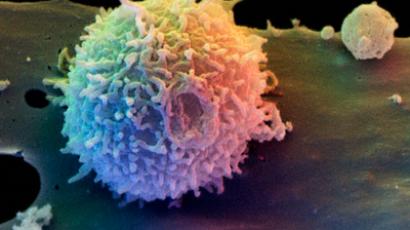

The researchers at Penn Medicine, led by Dr. Carl June, focus on using patient's own immune cells ‒ known as T-cells, a type of white blood cells ‒ and HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

"It's a disabled virus," June explained to KSL. "But it retains the one essential feature of HIV, which is the ability to insert new genes into cells.”

The experimental therapy, called T-cell immunotherapy, works by removing billions of the patient's T-cells from the blood and genetically modifying or reprogramming them with a disabled form of HIV in the laboratory. This modification or reprogramming allows them to potentially target and kill their own malignant cells. The modified cells ‒ now called CTL019 cells ‒ are then grown in the laboratory and re-infused into the patient. When the patient's own T-cells recognize and bind to the malignant cell, they have the ability to become activated and kill it, according to the Abramson Cancer Center.

June told KSL that the CTL019 cells, which he refers to as "serial killers," stay dormant in the body unless the cancer returns.

The link between leukemia and HIV goes back to 2006, when Timothy Brown, an HIV-positive patient was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. During the course of his treatment, he eventually had a bone marrow transplant from a donor with a rare genetic mutation. The transplant not only treated Brown's leukemia but had also eliminated the HIV from his system, the doctors treating him announced in a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Brown, who became known as the Berlin Patient, became the first man to ever be fully cured of HIV.

His case caused a revolution in research that focused on using the immune system to kill cancer cells.

In 2012, seven-year-old Emma Whitehead became the first child to undergo T-cell immunotherapy, as well as the first patient to be treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Two months after the April procedure, testing revealed there was no sign of cancer in the girl’s body.

Whitehead and Jensen were both part of a study by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (Penn Medicine) that was published in The New England Journal of Medicine in October. There were a total of 30 acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients involved: five adults ages 26 to 60, and 25 children and young adults ages 5 to 22. Six months after being treated, 23 of the 30 patients were still alive, and 19 of them have remained in complete remission, the New York Times reported.

“We have a number of patients who are a year or more out and are in remission and not requiring other therapies,” said Dr. Stephan A. Grupp, who led the part of the study done at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He told the Times those long remissions gave the researchers hope that the treatment would have lasting effects.

June described the effectiveness of the treatment as “beyond my expectations.”

In July, the Food and Drug Administration designated the T-cell treatment a “breakthrough therapy” for relapsed and treatment-resistant acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults and children. The designation recognizes experimental drugs “that may demonstrate substantial improvement over existing therapies” for life-threatening conditions, and is meant to speed their development and review, according to the Times.

Jensen returned home Thursday to a celebration organized by his neighbors, KSL reported.

“It really has been an experience that we have all been a part of, instead of just them battling it by themselves,” a neighbor said.

June’s next step will be to use the gene therapy on other types of cancers.