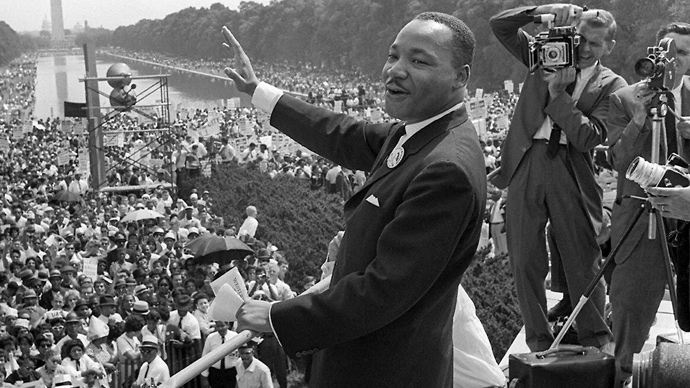

Revealed: FBI attempted to drive MLK to suicide

The publication this week of a 1964 letter sent by the FBI to Martin Luther King in which he’s urged to commit suicide reveals never-before-seen details about the government’s campaign to sabotage the civil rights leader.

On Tuesday, Beverly Gage wrote for the New York Times about the history of the letter which, until then, had been largely shrouded in secrecy, as have other clandestine FBI operations that sought to discredit alleged opponents of the United States government under the helm of then director J Edgar Hoover through a covert campaign of disinformation, blackmail and harassment.

“When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. received this letter, nearly 50 years ago, he quietly informed friends that someone wanted him to kill himself — and he thought he knew who that someone was. Despite its half-baked prose, self-conscious amateurism and other attempts at misdirection, King was certain the letter had come from the FBI. Its infamous director, J. Edgar Hoover, made no secret of his desire to see King discredited. A little more than a decade later, the Senate’s Church Committee on intelligence overreach confirmed King’s suspicion,” Gage wrote.

“There is only one thing left for you to do,” King is warned by the unknown author in the final paragraph of the letter published in unredacted form for the first time this week. “You know what it is.”

Prior to the ominous plea for King to commit suicide in the letter’s final paragraph, the author uses the word “evil” no fewer than a half-dozen times and accused him of being “a dissolute, abnormal moral imbecile.”

“Your ‘honorary’ degrees, your Nobel Prize (what a grim farce) and other awards will not save you. King, I repeat you are done,” it continues.

“No person can overcome facts, not even a fraud like yourself… I repeat — no person can argue successfully against facts… Satan could not do more. What incredible evilness… King you are done.”

Gage, a history professor at Yale University currently at work on a biography of Hoover, explained to the Times that she found the letter in its uncensored form, “rife with typos and misspellings and sprinkled with attempts at emending them,” this summer while scouring for information at the National Archives.

“The uncovered passages contain explicit allegations about King’s sex life, rendered in the racially charged language of the Jim Crow era. Looking past the viciousness of the accusations, the letter offers a potent warning for readers today about the danger of domestic surveillance in an age with less reserved mass media,” Gage wrote.

Indeed, the Electronic Frontier Foundation — a California-based advocacy and legal group that fights against government spying, among other intrusions — said in response that the letter “demonstrates exactly what lengths the intelligence community is willing to go to — and what happens when they take the fruits of the surveillance they’ve done and unleash it on a target.”

“The implications of these types of strategies in the digital age are chilling. Imagine Facebook chats, porn viewing history, emails, and more made public to discredit a leader who threatens the status quo, or used to blackmail a reluctant target into becoming an FBI informant. These are not far-fetched ideas. They are the reality of what happens when the surveillance state is allowed to grow out of control, and the full King letter, as well as current intelligence community practices illustrate that reality richly,” wrote Nadia Kayyali.

The FBI has long taken heat for its surveillance of King and others during the Vietnam War era in particular. In 1971, a team of activists burglarized a FBI field office in Pennsylvania and later unearthed proof of a program, COINTELPRO, in which the bureau waged a misinformation campaign against King and other anti-war advocates after he called the FBI ‘‘completely ineffectual in resolving the continued mayhem and brutality inflicted upon the Negro in the deep South’’

“Hoover deployed agents to find subversive material on King, and Robert Kennedy authorized wiretaps on King’s home and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) offices in October 1963” as part of that program, recalls an article on the Stanford University website. “Hoover continued to approve investigations of King and covert operations to discredit King’s standing among financial supporters, church leaders, government officials and the media.”

King died in 1968 when he was assassinated at a motel in Alabama following more than a decade of activism that played a pivotal role in securing civil rights for African-Americans and other minorities in the US.