A little bit of fat goes a long way to fighting staph infections - study

It seems those extra holiday pounds could actually be good for your health. A study has found that fat cells under the skin may protect against the most prevalent type of staph infection by producing molecules that can directly kill invasive pathogens.

Richard Gallo, MD, PhD, professor, and chief of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, and his colleagues have uncovered a previously unknown role for dermal fat cells, known as adipocytes: they produce antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that help fend off invading bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and other pathogens.

"Fat has an additional role we didn't suspect," Jay Kolls of the University of Pittsburgh told New Scientist, referring to a study published in the January issue of Science.

“It was thought that once the skin barrier was broken, it was entirely the responsibility of circulating [white] blood cells like neutrophils and macrophages to protect us from getting sepsis,” Gallo, the study’s principal investigator, said in a UCSD Health statement.

“But it takes time to recruit these cells [to the wound site]. We now show that the fat stem cells are responsible for protecting us. That was totally unexpected,” he added. “It was not known that adipocytes could produce antimicrobials, let alone that they make almost as much as a neutrophil.”

Gallo’s lab had previously published work observing the presence of S. aureus in the fat layer of skin, so researchers looked to see if the subcutaneous fat played a role in preventing skin infections like staph.

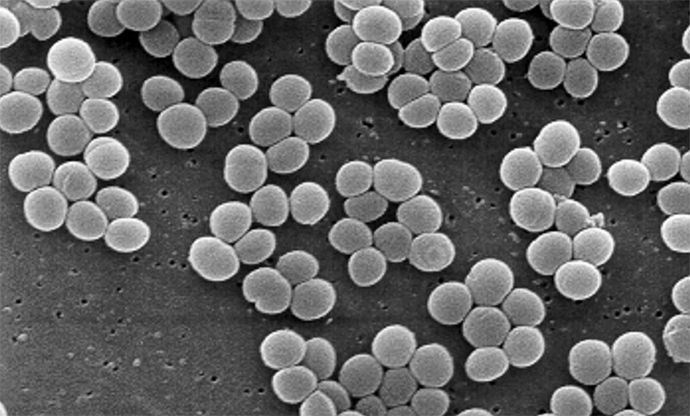

Staph infections range from a simple boil to antibiotic-resistant infections, to flesh-eating infections. The difference between these is the strength of the infection, how deep it goes, how fast it spreads, and how treatable it is with antibiotics. They are caused by any of several types of Staphylococcus bacteria ‒ of which S. aureus is the most common ‒ which are found on people’s skin or in their noses (regardless of health).

Most of the time, these bacteria cause no problems or result in relatively minor skin infections. But staph can quickly turn deadly if the bacteria enters the bloodstream, bones, or organs ‒ or if antibiotics are ineffective, such as with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections.

To perform the research on adipocytes, Dr. Ling-juan Zhang, the first author of the paper, exposed mice to S. aureus. Within hours, she detected a major increase in both the number and size of fat cells at the site of infection. Not only that, but the adipocytes produced high levels of a specific type of AMP called cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide or CAMP, the statement said. Cathelicidin interferes with the cell membranes of bacteria and is also known to harm viruses, though no one quite knows how, according to Gizmodo.

“AMPs are our natural first line defense against infection. They are evolutionarily ancient and used by all living organisms to protect themselves,” said Gallo.

Gallo and Zhang compared their results against a group of mice that were genetically modified to hold very little fat. The second set of rodents developed much worse infections from the same bacteria.

But more fat doesn’t mean more protection, the researchers noted. Further tests confirmed that human adipocytes also produce cathelicidin, suggesting the immune response is similar in both rodents and humans. In those tests, obese subjects were observed to have more CAMP in their blood than subjects of normal weight.

Too few CAMP present in a person’s immune system can lead to frequent infections ‒ such as a type of eczema ‒ while too much CAMP “can drive autoimmune and other inflammatory diseases like lupus, psoriasis and rosacea,” Gallo said in the statement.

"A little bit of fat is good – too much is not good," said Kolls, who was not involved with the study but wrote an accompanying editorial on it for Science.

Defective AMP production by fat cells could be caused by obesity or insulin resistance (from diabetes), and may lead to higher risk of infections, Gallo said. Too much cathelicidin could create an “unhealthy” inflammatory response, he added.

The lead investigator is excited about where the research could lead.

“The key is that we now know this part of the immune response puzzle. It opens fantastic new options for study. For example, current drugs designed for use in diabetics might be beneficial to other people who need to boost this aspect of immunity,” he said. “Conversely, these findings may help researchers understand disease associations with obesity and develop new strategies to optimize care.”