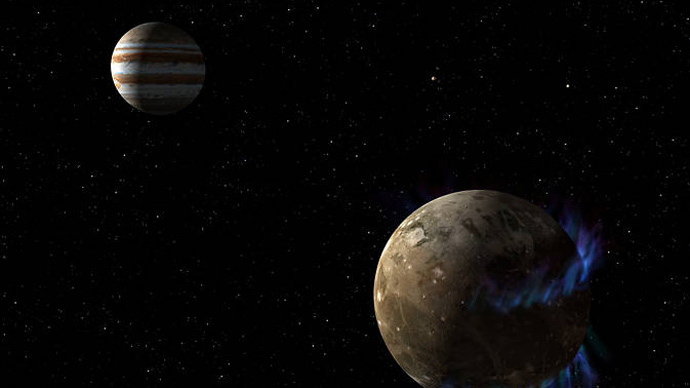

New data suggests Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, the largest in the solar system, has an underground ocean which contains more water than all of Earth's surface water combined, according to NASA.

NASA scientists were able to use the Hubble Space Telescope to collect more than seven hours of data about the auroral belts on the Ganymede moon, which are caused by its magnetic fields. An aurora is created by charged particles interacting with an atmosphere.

The existence of them alone doesn’t mean there’s an ocean, but oceans do affect aurorae movements. Less movement locks the aurorae in a stable position and could indicate a salty, electrically conductive ocean. Scientists noticed that movement was limited to two degrees, instead of the six degrees they would observe if an ocean wasn’t present.

READ MORE: No water needed: Methane-based life possible on Saturn’s moon Titan, study says

"I was always brainstorming how we could use a telescope in other ways," said Joachim Saur from the University of Cologne in Germany, who led the NASA team, in a released statement.

"Is there a way you could use a telescope to look inside a planetary body? Then I thought, the aurorae! Because aurorae are controlled by the magnetic field, if you observe the aurorae in an appropriate way, you learn something about the magnetic field. If you know the magnetic field, then you know something about the moon’s interior."

NASA made the announcement in a teleconference on Thursday, saying the telescope confirmed a long-standing theory from the 1970s that Ganymede was home to an ocean about 60 miles beneath its surface. The only evidence to date was collected during brief flybys with the Galileo spacecraft in the early 2000s.

The subterranean ocean on Ganymede is thought to have more water than all the water on Earth's surface. NASA’s efforts to identify liquid water are crucial in the search for habitable worlds beyond Earth, and for the search of life elsewhere in the solar system.

Studying the ocean will be difficult even with a robot, however, because it lies 60 miles below the surface, under layers of ice, and probably lacks a hydrothermal system, according to NASA. A mission back to the Jupiter system, called JUICE, is being planned by the European Space Agency in the 2020s. It will aim to take a closer look at the moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto – all three of which are thought to have oceans.

"As far as we can tell, almost everywhere we look there's water," Heidi Hammel, executive vice president of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, said during the conference. "Water, water, everywhere in our solar system."

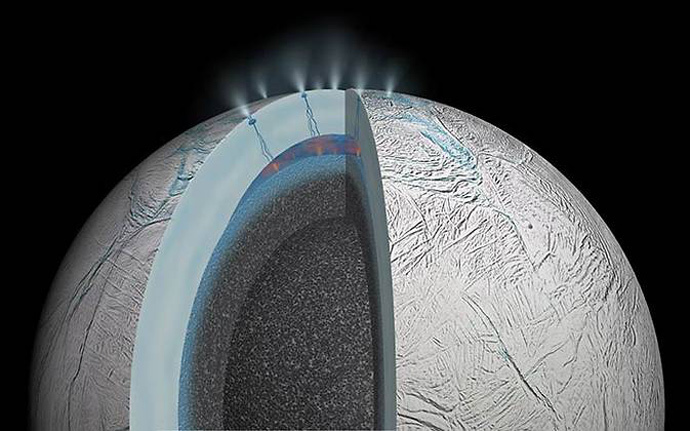

Saturn’s moon Enceladus suspected of housing hydrothermal ocean

Meanwhile, a hydrothermal system is suspected to exist on Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Passing spacecraft have seen trenches and ridges like on Earth, and a 2005 NASA Cassini mission recorded ice geysers streaming from its south pole.

New analysis in two papers based on research from Cassini’s mission suggests Enceladus’ ocean is being heated from the bottom up, exhibiting Earth-like hydrothermal activity that could explain the plumes of ice at its south pole.

“These findings add to the possibility that Enceladus, which contains a subsurface ocean and displays remarkable geologic activity, could contain environments suitable for living organisms,” John Grunsfeld, an astronaut and associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington, said in a statement.

“The locations in our solar system where extreme environments occur in which life might exist may bring us closer to answering the question: are we alone in the Universe?”

READ MORE: NASA successfully tests megarocket booster for deep-space system (VIDEO)

Hydrothermal activity occurs when seawater infiltrates and reacts with a rocky crust and emerges as a heated mineral-laden solution, according to NASA.

The team used the Cassini spacecraft, which orbits Saturn, to detect tiny particles of silica floating in space. It's not sand exactly, but researchers think the particles did come from the bottom of Enceladus' ocean. The silica particles could only be made if that ocean were hot.

"We think that the temperature at least in some part of the ocean must be higher than 190 degrees Fahrenheit," Sean Hsu, of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado at Boulder, said in a statement.

"If you could swim a little bit further from the really hot part then it could be comfy."

Later this year, the Cassini spacecraft will skim past Enceladus at a distance of just 30 miles. It should provide one of the best opportunities yet to learn about what's going on inside.