Alabama’s legislative districts are ‘racially gerrymandered,' Supreme Court rules

The Supreme Court has ruled that Alabama’s redistricting plans weaken blacks’ political power by concentrating them together, thus increasing Republican power. Justices sent the case back to the same District Court that had okayed Alabama’s new maps.

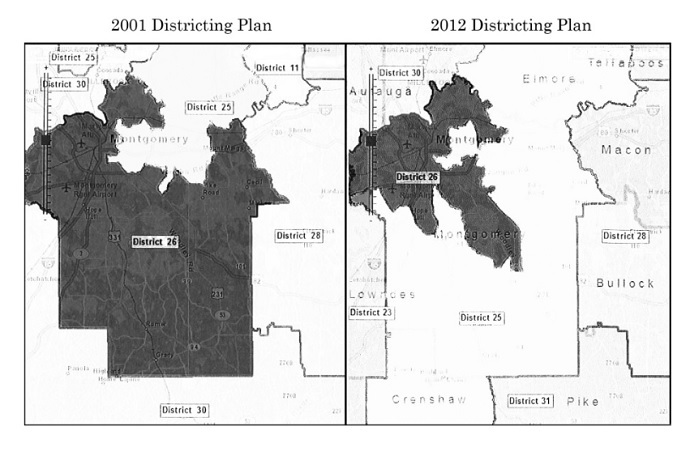

In 2012, Alabama’s Republican-led state legislature re-drew the boundaries of the state legislature’s 105 House districts and 35 Senate districts. It focused on obtaining the theoretical ideal of precisely equal population by keeping any deviation from that goal to less than one percent. Alabama also sought to avoid hampering racial minorities’ ability to elect their candidates of choice ‒ as required by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 ‒ by maintaining roughly the same percentage of African-Americans in majority-minority districts that existed within the previous district lines.

The Alabama Legislative Black Caucus and the Alabama Democratic Conference each sued the state in August 2012 over the redistricting plans; the two cases were subsequently consolidated. The appellants claimed the new district boundaries created “racial gerrymanders” in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause ‒ a question the Supreme Court ignored ‒ and the Voting Rights Act.

In December 2013, a three-judge panel from the US District Court voted 2-1 to uphold the Alabama redistricting map. The District Court ruled that the claims of racial gerrymandering failed because “[r]ace was not the predominant motivating factor.” The judges believed the appellants needed to prove that racial gerrymandering occurred on a statewide basis as well, which they were unable to do.

The District Court also ruled that the plaintiffs lacked standing because the record did “not clearly identify the districts in which the individual members of the [Conference] reside,” and that the Conference had “not proved that it has members who have standing to pursue any district-specific claims of racial gerrymandering.”

Supreme Court decision

In a 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court disagreed with that decision. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote the majority opinion, in which Justices Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan joined.

Breyer applauded Alabama’s attempt to create an idealistic “one-person, one-vote” situation by limiting the deviation from the goal population to one percent, but noted that a five percent deviation from the ideal is “generally permissible.” However, he disliked how the state went about drawing district boundaries to obtain that goal.

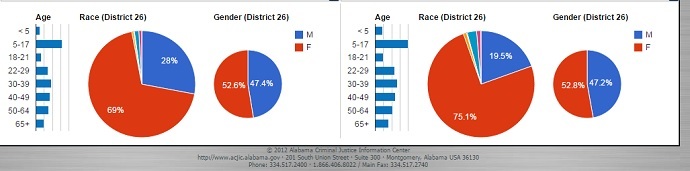

“In order for Senate District 26, for example, to meet the State’s no-more-than-1 [percent] population-deviation objective, the State would have to add about 16,000 individuals to the district. And, prior to redistricting, 72.75 [percent] of District 26’s population was black. Accordingly, Alabama’s plan added 15,785 new individuals, and only 36 of those newly added individuals were white,” he wrote, adding that was “a remarkable feat given the local demographics.”

The Supreme Court cited the Department of Justice Guidelines for Section 5’s pre-clearance determinations, which say that districts are not based “on any predetermined or fixed demographic percentages.”

The majority opinion also held that the appellants didn’t claim that the Alabama legislature employed racial gerrymandering as a whole, but that individual majority-minority districts were racially gerrymandered, and that the evidence of such required looking at the state as a whole.

“And those are the districts that we believe the District Court must reconsider,” Breyer noted. “That Alabama expressly adopted and applied a policy of prioritizing mechanical racial targets above all other districting criteria (save one-person, one-vote) provides evidence that race motivated the drawing of particular lines in multiple districts in the State.”

When it came to standing, the Supreme Court disagreed with the District Court, writing that “the common sense inference is strong enough to lead the Conference reasonably to believe that, in the absence of a state challenge or a court request for more detailed information, it need not provide additional information such as a specific membership list.”

Dissenting opinions

In a scathing dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia called the majority’s decision a “sweeping holding that will have profound implications for the constitutional ideal of one person, one vote, for the future of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and for the primacy of the State in managing its own elections.”

“If the Court’s destination seems fantastical, just wait until you see the journey,” he added.

Joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, Scalia sided with the District Court’s opinion on the appellants’ standing, writing that they did not prove that they sufficiently represented members in the affected Alabama districts, as counties and districts have different boundaries.

“Frankly, I do not know what to make of appellants’ arguments. They are pleaded with such opacity that, squinting hard enough, one can find them to contain just about anything,” Scalia concluded. “This, the Court believes, justifies demanding that the District Court go back and squint harder, so that it may divine some new means of construing the filings.”

In a dissent of his own, Thomas ‒ the Supreme Court’s only black justice ‒ focused on the effective racism that resulted as a consequence of Section 5 and the Supreme Court’s role in creating Alabama’s current redistricting problems.

“The practice of creating highly packed ‒ 'safe' ‒ majority-minority districts is the product of our erroneous jurisprudence, which created a system that forces States to segregate voters into districts based on the color of their skin” he wrote. “Nor does this Court have clean hands.”

“I do not pretend that Alabama is blameless when it comes to its sordid history of racial politics. But, today the State is not the one that is culpable. Its redistricting effort was indeed tainted, but it was tainted by our voting rights jurisprudence and the uses to which the Voting Rights Act has been put,” Thomas added. “Long ago, the DOJ and special-interest groups like the [American Civil Liberties Union] hijacked the Act, and they have been using it ever since to achieve their vision of maximized black electoral strength, often at the expense of the voters they purport to help.”