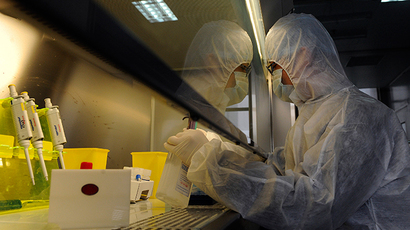

Lab for genetic modification of human embryos just $2,000 away – report

With the right expertise in molecular biology, one could start a basic laboratory to modify human embryos using a genome-editing computer technique all for a couple thousand dollars, according to a new report.

Genetic modification has received heightened scrutiny recently following last week’s announcement that Chinese researchers had, for the first time, successfully edited human embryos’ genomes. The team at Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou, China, used CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats), a technique that relies on “cellular machinery” used by bacteria in defense against viruses.

This machinery is copied and altered to create specific gene-editing complexes, which include the wonder enzyme Cas9. The enzyme works its way into the DNA and can be used to alter the molecule from the inside. The combination is attached to an RNA guide that takes the gene-editing complex to its target, telling Cas9 where to operate.

Use of the CRISPR technique is not necessarily relegated to the likes of cash-flush university research operations, according to a report by Business Insider.

READ MORE: ‘Editing DNA’ to eliminate genetic conditions now a reality

Geneticist George Church, who runs a top CRISPR research program at the Harvard Medical School, said the technique could be employed with expert knowledge and about half of the money needed to pay for an average annual federal healthcare plan in 2014 -- not to mention access to human embryos.

"You could conceivably set up a CRISPR lab for $2,000,” he said, according to Business Insider.

Other top researchers have echoed this sentiment.

"Any scientist with molecular biology skills and knowledge of how to work with [embryos] is going to be able to do this,” Jennifer Doudna, a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, recently told MIT Tech Review, which reported that Doudna co-discovered how to edit genetic code using CRISPR in 2012.

Last week, the Sun Yat-Sen University research team said it attempted to cure a gene defect that causes beta-thalassemia (a genetic blood disorder that could lead to severe anemia, poor growth, skeletal abnormalities and even death) by editing the germ line. For that purpose they used a gene-editing technique based on injecting non-viable embryos with a complex, which consists of a protective DNA element obtained from bacteria and a specific protein.

"I suspect this week will go down as a pivotal moment in the history of medicine," wrote science journalist Carl Zimmer for National Geographic.

READ MORE: EU top court clears path for stem cell patenting

Response to the new research has been mixed. Some experts say the gene editing could help defeat genetic diseases even before birth. Others expressed concern.

“At present, the potential safety and efficacy issues arising from the use of this technology must be thoroughly investigated and understood before any attempts at human engineering are sanctioned, if ever, for clinical testing,” a group of scientists, including some who had worked to develop CRISPR, warned in Science magazine.

Meanwhile, the director of the US National Institutes for Health (NIH) said the agency would not fund such editing of human embryo genes.

“Research using genomic editing technologies can and are being funded by NIH,” Francis Collins said Wednesday. “However, NIH will not fund any use of gene-editing technologies in human embryos. The concept of altering the human germline in embryos for clinical purposes ... has been viewed almost universally as a line that should not be crossed.”

Although the discovery of CRISPR sequences dates back to 1987 – when it was first used to cure bacteria of viruses – its successes in higher animals and humans were only achieved in 2012-13, when scientists achieved a revolution by combining the resulting treatment system with Cas9 for the first time.

READ MORE: MPs approve draft ‘3 parent baby’ law

On April 17, the MIT’s Broad Institute announced that has been awarded the first-ever patent for working with the Crisp-Cas9 system.

The institute’s director, Eric Lander, sees the combination as “an extraordinary, powerful tool. The ability to edit a genome makes it possible to discover the biological mechanisms underlying human biology.”

The system’s advantage over other methods is in that it can also target several genes at the same time, working its way through tens of thousands of so-called 'guide' RNA sequences that lead them to the weapon to its DNA targets.

Meanwhile, last month in the UK, a healthy baby was born from an embryo screened for genetic diseases, using karyomapping, a breakthrough testing method that allows doctors to identify about 60 debilitating hereditary disorders.