Michigan task force blames state, emergency manager law for Flint crisis

Responsibility for the Flint water crisis lies primarily with Michigan’s state government and the emergency managers that were placed in charge of the city, according to a new report calling the scandal “a clear case of environmental injustice.”

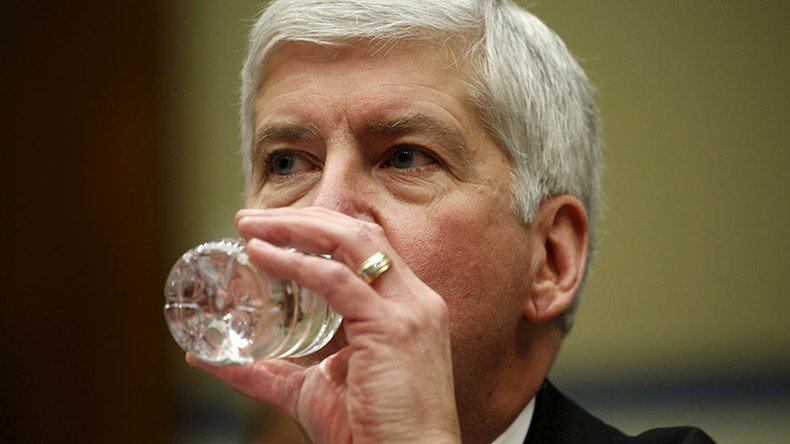

The report, issued by a task force appointed by Michigan Governor Rick Snyder, called the contamination of water with lead in Flint “a story of government failure, intransigence, unpreparedness, delay, inaction, and environmental injustice.” It found that, while failures did occur on all levels of government, the state was primarily responsible for creating the crisis as a result of decisions by its regulatory agencies and emergency managers.

Michigan’s controversial emergency manager law allows state appointees to “replace local representative decision-making in Flint, removing the checks and balances and public accountability that come with public decision-making,” the report said.

Michiganders have hotly debated who was responsible for tapping the corrosive Flint River as a drinking water source, but the report makes it clear that the emergency managers, not locally elected officials, made the decision.

“Emergency managers made key decisions that contributed to the crisis, from the use of the Flint River to delays in reconnecting to DWSD [Detroit Water and Sewerage Department] once water quality problems were encountered,” the report read. “Given the demographics of Flint, the implications for environmental injustice cannot be ignored or dismissed.”

Noting that 57 percent of Flint’s population is black and that the city is extremely impoverished, the task force stated that residents “did not enjoy the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards as that provided to other communities.”

“By virtue of their being subject to emergency management, Flint residents were not provided equal access to, and meaningful involvement in, the government decision-making process,” the report found.

The task force called on lawmakers to review the emergency manager law and propose changes that can allow local governments to act as a check on state appointees. It also suggested considering alternatives to the law, such as allowing for local concerns to impact decision-making and permitting residents to appeal decisions.

While criticizing the role of emergency managers, the report said the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality bore primary responsibility for the actual contamination of Flint’s water. The agency did not properly treat the river water with anti-corrosives, allowing it to leach away lead from service lines as it flowed towards homes and other buildings.

According to the report, this happened because MDEQ misinterpreted the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Lead and Copper Rule, leading to underreported lead levels and exposure to contaminated water. It also found “cultural shortcomings that prevent it from adequately serving and protecting the public health of Michigan residents.”

Additionally, the task force concluded that MDEQ waited several months to accept the EPA’s offer to consult with its lead experts, and failed to investigate whether the Flint River water was contributing to an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in the city.

‘Crime of epic proportions’: Congress grills ex-EPA, Flint emergency manger https://t.co/6HHZJvzzv4pic.twitter.com/otFpKwmavP

— RT America (@RT_America) March 16, 2016

MDEQ “failed in its fundamental responsibility to effectively enforce drinking water regulations,” the task force stated. “The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) failed to adequately and promptly act to protect public health.”

“Both agencies, but principally the MDEQ, stubbornly worked to discredit and dismiss others’ attempts to bring the issues of unsafe water, lead contamination, and increased cases of Legionellosis (Legionnaires’ disease) to light,” it added.

The report did not spare Snyder, saying that the “ultimate accountability” for the crisis rests with him.

“Neither the Governor nor the Governor’s office took steps to reverse poor decisions by MDEQ and state-appointed emergency managers until October 2015, in spite of mounting problems and suggestions to do so by senior staff members in the Governor’s office," the task force said. “The significant consequences of these failures for Flint will be long-lasting. They have deeply affected Flint’s public health, its economic future, and residents’ trust in government.”

Also found wanting were the EPA for failing to exercise its authority and for being slow to insist on corrosion control, the City of Flint for being ill-prepared to operate its water treatment plant and for failing to comply with EPA regulations, and the Genesee County Health Department for poor communication and coordination.

The task force was appointed by the Republican governor in October, in response to growing outrage over the crisis. State officials had denied for months that the water was poisoned, insisting that it was safe for residents to drink, until experts and a local doctor revealed children were being diagnosed with elevated levels of lead in their blood.

A report from the task force in December resulted in an apology from Snyder, after it found that MDEQ was mostly responsible. Agency Director Dan Wyant and spokesman Brad Wurfel both resigned as a result.

The new report arrives as speculation about a possible cover-up is growing in Flint. In December, a mysterious break-in ‒ a mini-Watergate, so to speak ‒ was reported at a room in Flint City Hall that was holding files related to the water crisis. Flint Mayor Karen Weaver said documents were found scattered around the room, making it impossible to know what, if anything, was stolen.

Flint crisis ‘a catastrophe’: Families file class-action lawsuit over poisoned water https://t.co/a9aydYaJInpic.twitter.com/wJX8Zme941

— RT America (@RT_America) March 7, 2016

Three months later, police still don’t know who broke in. Other than a television that was taken, there are no new leads, but Flint Police Chief Tim Johnson called it an “inside job” that occurred while investigations were beginning to take shape.

"It was definitely an inside job. The power cord [to the TV] wasn't even taken. The average drug user knows that you'd need the power cord to be able to pawn it," Johnson said on Friday, according to the Flint Journal.

Also suspicious is the fact that no city employees were assigned to the office when it was broken into.

"It was somebody that had knowledge of those documents that really wanted to keep them out of the right hands,” Johnson said, “out of the hands of someone who was going to tell the real story of what's going on with Flint water.”