Step closer to AIDS cure: US scientists ‘cut out’ HIV DNA from infected animals

A cure for AIDS now seems to be closer than ever, since US scientists have managed to “cut out” the HIV virus DNA from the genomes of living animals for the first time. They hope that one day their “molecular scissors” will help cure AIDS in humans.

Researchers at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University have successfully eliminated HIV-1 genes from the genomes of mice and rats in which nearly every each cell from blood to brain had the virus responsible for AIDS.

“In a proof-of-concept study, we show that our gene editing technology can be effectively delivered to many organs of two small animal models and excise large fragments of viral DNA from the host cell genome,” said Professor Kamel Khalili, who led the study.

As of now, HIV treatment requires a combination of antiretroviral drugs. While they certainly help most patients support their lives by suppressing HIV replication, neither of the existing protocols “delete” HIV-1 DNA from infected cells. In fact, in cases when the therapy is interrupted or stopped, the virus starts spreading so quickly that patients risk getting full-blown AIDS.

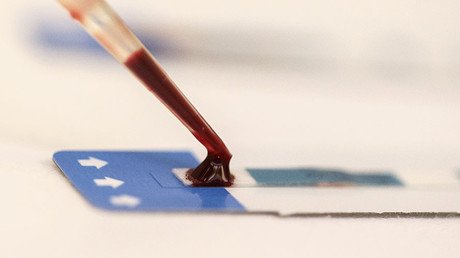

The ability to entirely “cut out” HIV-1 genes from DNA is what makes the technology of Professor Khalili and his team a real step forward. The key element of the potential cure is a technology called CRISPR/Cas9, or in a non-scientific language, “molecular scissors.”

In a previous study, the researchers used CRISPR to eliminate HIV from cells grown in a lab dish and those taken from HIV-positive patients. They saw that viral replication was significantly reduced after the gene editing system treatment, without having any adverse effect on the host cells.

The current study is a follow-up, because the researchers wanted to see whether they would be able to snip out HIV-1 in infected rats and mice. To deliver that technology to cells in living rodents, Khalili and his team also used a system called a recombinant adeno-associated viral (rAAV) vector delivery system.

'It's only the beginning': First ‘HIV-to-HIV liver transplant’ performed by US doctors https://t.co/FnKISFORySpic.twitter.com/ZfmoyHYVfP

— RT (@RT_com) April 1, 2016

Two weeks after the rAAV CRISPR/Cas-9 molecules were injected into the rodents’ bloodstream, the scientists found that a large segment of HIV-1 DNA that their treatment targeted had been removed from the animals’ viral genome in every tissue, including the brain, heart, kidney, liver, lungs, spleen, and blood cells. Levels of HIV-1 DNA were significantly reduced in lymphocytes and in lymph nodes.

“The ability of the rAAV delivery system to enter many organs containing the HIV-1 genome and edit the viral DNA is an important indication that this strategy can also overcome viral reactivation from latently infected cells and potentially serve as a curative approach for patients with HIV,” said Dr. Khalili.

While there may be cause for exuberant optimism, there is much work still to be done, HIV researchers say.

“I’d say [this is] a wide step forward, but clearly there are many other hurdles and barriers along the way that we have to overcome in the future,” Dr. Chen Liang of McGill University, whose work focuses on using gene editing to remove HIV DNA from human cells, told RT. “Humans are different than mice, and in their study, their mice do not have live HIV virus, but have integrated virus. If you attack a live virus, often the virus can become resistant.”

The next step would be testing the technology on a larger group of animals, in which the researchers plan to monitor for effects of the treatment.

Khalili and his colleagues hope that their technique will eventually become a way to treat people infected with HIV. However, it will first take a clinical trial that could happen within the next several years.