Taxpayers foot the bill after NFL waged campaign to keep critic from concussion grant money

The NFL improperly pressured the government not to select a specific researcher for a concussion-related grant funded by an “unrestricted” gift from the league, according to a new congressional report. US taxpayers funded the study instead.

The National Football League has been under fire for years, with current and former players accusing the league of hiding evidence of the dangers of head traumas. At least 90 out of the 94 former professional football players ‒ or 96 percent ‒ studied by Dr. Ann McKee, chief of neuropathology at the Department of Veterans Affairs in Boston and a professor of neurology and pathology at the Boston University School of Medicine, were posthumously diagnosed with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). The latest is Bubba Smith.

Super Bowl’s 50th birthday marred by concussion & homeless scandals https://t.co/n3KfvJ02GSpic.twitter.com/mtpqsxSRq6

— RT America (@RT_America) February 6, 2016

On Monday, the House Energy and Commerce Committee released the results of its investigation into whether the NFL improperly tried to prevent the National Institutes of Health from granting research money to a prominent Boston University expert on neurodegenerative diseases. The allegations, confirmed by the 91-page congressional report, were initially raised by ESPN in December.

No strings attached… sort of

In 2012, the NFL donated $30 million to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to fund the study of sports-related injuries, specifically the “serious medical conditions prominent in athletes” that are also relevant to the general population. The gift was explicitly described as “unrestricted” and came “with no strings attached,” according to a press release at the time. Two years later, however, the league clarified that it had veto power over the projects it funds, ESPN reported.

By that point, the NFL had been under fire for several years from former players and outside researchers, who claimed the league had hidden the effects of traumatic brain injuries (TBI) from players who were thus not able to properly assess the risks of playing. The first lawsuits containing these accusations were filed in 2009.

At the same time, the research into CTE ‒ a disease that many veterans suffer from as well ‒ was expanding, notably at the Boston University School of Medicine’s CTE Center, established in 1996. Athletes with a history of repetitive brain trauma are prone to being diagnosed with CTE, which involves the building-up on the brain tissue of an abnormal protein called tau, according to the Sports Legacy Institute, a Boston-based nonprofit. Although CTE can only be diagnosed with a post-mortem examination, its symptoms include memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, paranoia, impulse control problems, aggression, depression, and progressive dementia before death.

An outspoken critic applies for a grant

The BU center’s director of clinical research, Dr. Robert Stern, is an outspoken critic of the NFL. In October 2014, he sided with players who had filed a class-action lawsuit, claiming that the league had hidden the effects of traumatic brain injuries from players who were thus not able to properly assess the risks of playing. Stern also applied for $16 million in grant funding for a seven-year study that aims to find a way to detect CTE in living players.

In May 2015, the NIH recommended that Stern receive the money. Midway through the process of issuing the Notice of Grant Award, however, members of the NFL’s Head, Neck and Spine Committee stepped in, according the congressional report. In mid-June, Dr. Elliot Pellman, the NFL medical director who once ran the league's discredited concussion research program, emailed the executive director of the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH), writing that the NFL had “significant concerns [regarding] BU and their ability to be unbiased and collaborative.” He asked that the FNIH “slow down the process until we all have a chance to speak and figure this out.”

Less than a week later, the NFL stepped in again. The league’s chief health and medical adviser, Dr. Betsy Nabel, emailed the director of NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, attaching Stern’s 61-page affidavit in support of the class-action lawsuit.

“I hope this group is able to approach their research in an unbiased manner,” Nabel wrote.

At the end of June, NFL representatives told the NIH on a conference call that the league “could not recommend that the NFL fund the BU study” because they felt that “Dr. Stern had a conflict of interest and that the grant application process had been tainted by bias.”

When the NIH refused to change its stance on awarding the grant to Stern, the NFL reversed its commitment to fund the study, ESPN’s ‘Outside the Lines’ reported in December. The government decided to go ahead and fund the study without help from the NFL, however. As a result, American taxpayers footed the bill.

Improper influence

“This investigation confirms the NFL inappropriately attempted to use its unrestricted gift as leverage to steer funding away from one of its critics,” Representative Frank Pallone (D-New Jersey), the ranking member on the House Energy and Commerce Committee said in a statement. “Since its research agreement with NIH was clear that it could not weigh in on the grant selection process, the NFL should never have tried to influence that process.”

The league denied the report’s findings that it acted improperly, and complained that the doctors on the NFL Head, Neck and Spine Committee were not consulted during the investigation.

“There is no dispute that there were concerns raised about both the nature of the study in question and possible conflicts of interest. These concerns were raised for review and consideration through the appropriate channels. Ultimately the funding decision was made by the FNIH/NIH, not the NFL,” league spokesman Brian McCarthy said in a statement.

McCarthy went on to note that, of the $30 million NFL commitment to the NIH, $6 million went to the Boston University School of Medicine and the Department of Veterans Affairs for a study on CTE and post-traumatic neurodegeneration.

“We continue to be very happy and grateful that the NIH has funded this multi-site study. We are looking forward to getting started and remain focused on the science,” BU’s CTE Center said in a statement to RT.

“The NIH has had a longstanding and successful partnership with the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH), which has provided the opportunity to fund innovative research projects that have benefitted from partial or complete support from the private sector. As the committee report indicates, NIH followed the scientific, peer-review process in funding the CTE study, and was not inappropriately influenced by outside forces,” the government institute told RT in a statement.

While the committee did find that the NIH “maintained the integrity of the science and the grant review process,” it noted that the FNIH “did not adequately fulfill its role of serving as an intermediary between the NIH and the NFL.” The report offered several recommendations to address the committee’s findings, steps which the NIH said it has already begun undertaking.

“This experience has reinforced the importance of clear lines of communication between NIH and FNIH,” the agency said. “NIH has already taken a number of important steps to clarify its roles and responsibilities in agreements with FNIH and outside donors, in order to ensure that the science is free of even the perception of inappropriate outside influence.”

The committee also found that the NFL’s “rationalization that the Boston University study did not match their request for a longitudinal study is unfounded.”

CTE diagnoses continue

The congressional report comes as a former NFL player was diagnosed with CTE and BU shared the findings of a clinical consensus panel about a 27-year-old former NFL player who had previously been diagnosed with CTE.

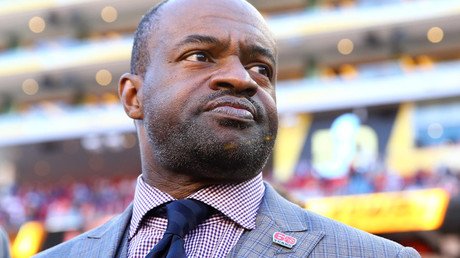

On Tuesday, the Department of Veterans Affairs, BU and the Concussion Legacy Foundation announced that Charles “Bubba” Smith, a former All-Pro defensive end who played nine seasons in the NFL, had Stage III CTE. His symptoms included cognitive impairment and problems with judgment and planning, the New York Times reported. Smith was 66 when he died in 2011, overdosing on the weight-loss drug phentermine.

Schools sack football teams due to deaths, injuries, lack of interest https://t.co/WIs7l6H1Pspic.twitter.com/7mEItA6mSz

— RT America (@RT_America) October 1, 2015

On May 18, the CTE Center posted about the unnamed 27-year-old, identified by previous news reports as Tyler Sash. The pathological diagnosis was that Sash, who played 23 games in the NFL, had Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Stage II/IV, marked by a 1-inch long lesion on the brain, according to previous remarks by McKee. The four stages of CTE correlate with a player’s age and the number of years he played football.

Sash’s levels of CTE were comparable to those of the late Junior Seau, who played in the NFL for 19 seasons and committed suicide at the age of 43, McKee told Think Progress in January. She had only seen one other case of someone so young with such an advanced case of the disease, she added. Sash died of an accidental overdose of pain medications in September.