Stanford researchers unexpectedly reverse brain damage with stem cells

Stanford researchers have found that injecting stem cells directly into the brains of recovering stroke sufferers is more than just safe – it actually reverses brain damage, something previously thought impossible by science.

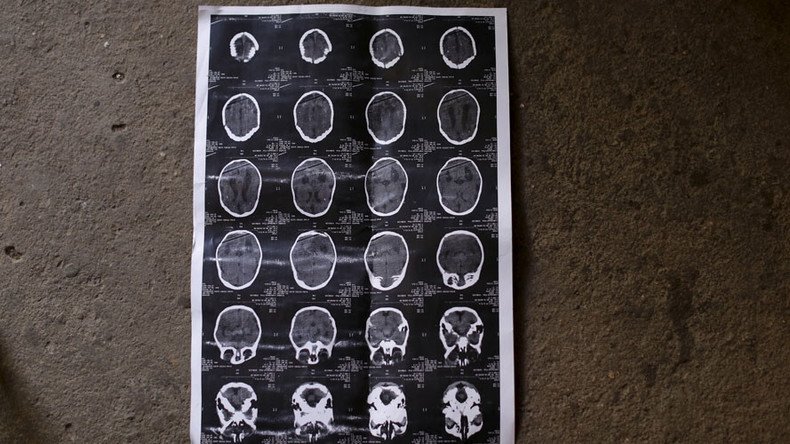

The amazing thing about the latest study, published in the journal Stroke, is that the arguably bigger success came about by accident. It was a small sample size of only 18 patients, and the objective was to test the safety of the procedure – which involves injecting stem cells directly under the uppermost layer of the brain. The tests showed that it is doable and relatively straightforward, as far as brain surgery goes.

But what “stunned” Stanford researchers was that the stem cells also reversed the damage way past the six-month recovery period after a stroke, beyond which it is thought the remaining unhealed brain circuits are completely beyond recovery. At that point, other therapy is normally stopped and the sufferer is left to live with whatever impairment remains.

A stroke is, essentially, a blood clot in the brain. If a person is lucky enough to survive one, they may lose a significant portion of their speech-making and motor faculties. While the functions may be restored in six months, they come back somewhat limited.

In the current study, scientists took a sample of recovering sufferers all at the stage of three to five years since the incidents, which is long after any existing treatment would still be administered. They drilled holes into the participants’ skulls and directly injected stem cells from adult donors into the grey matter.

With adverse effects rarely ranging beyond vomiting and headaches, the patients made a fast improvement. The physicians monitored recovery one, six and 12 months after the procedure, and noticed significant gains in speech, vision and motor skills.

The study “was designed primarily to test the procedure’s safety. But patients improved by several standard measures and their improvement was not only statistically significant, but clinically meaningful” lead author Gary Sternberg, who is also chair of neurosurgery at Stanford University in California, told The Washington Post. Sternberg personally oversaw the procedures.

“Their ability to move around has recovered visibly. That’s unprecedented. At six months out from a stroke, you don’t expect to see any further recovery.”

The patients were amazed by their recovery, and had control of limbs they had thought was lost completely.

What’s more, the Stanford team once more debunked an old assumption about the way stem cells actually affect us. It was earlier thought they create neurons upon entry, but the new research confirms the suspicion that they instead trigger a biochemical process that “[turns] the adult brain into the neonatal brain that recovers well.”

The researchers are still not entirely sure about the origins of this mysterious process, or whether it is the stem cells themselves triggering the recovery, or if the procedure is responsible for some sort of placebo effect that tricks the brain into action.

All of this feeds into the wider notion that dead brain pathways can be reactivated, according to Nicholas Boulis, a neurosurgeon at Emory University, who spoke to The Washington Post.

The technique also shows no immune rejection, and is a big step up from testing on rats.

There are over 7 million chronic stroke sufferers in the United States – and around 800,000 suffer one annually. That figure goes up to 15 million worldwide, with a large portion of them suffering irreversible damage - the type which the stem cell injections set out to cure. The findings here could greatly reduce the number of those suffering after failing to recover their neurologic functions.

Researchers are already looking at other types of damage previously thought to be permanent and incredibly hard to operate on, including the spinal cord – all of which has its roots in the brain. Further to the current study, Stanford is already hard at work on a follow-up, involving trials at multiple clinics and a bigger sample size of more than 150 participants.