Ethics concerns over human-animal hybrids as US govt agency seeks to lift funding ban

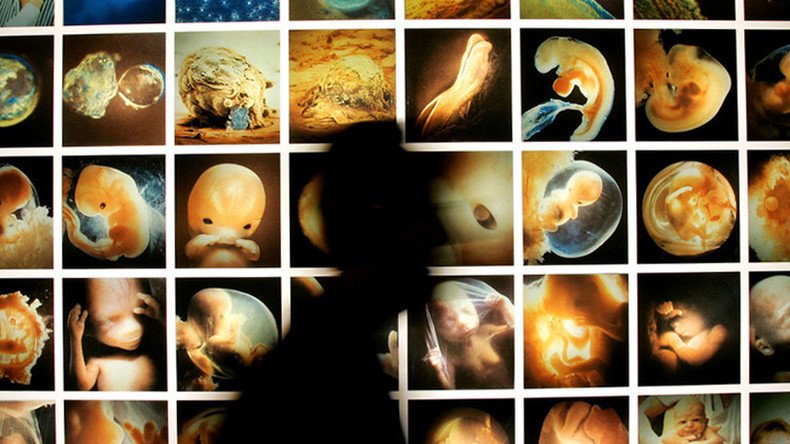

The US National Institutes of Health wants government money to fund research that would mix human cells into animal embryos. It is hoped it could lead to major breakthroughs to tackle diseases. Critics worry that it will raise serious ethical issues.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) had issued a moratorium on researching whether human cells could be used to modify animal brains a year ago. The 2009 NIH Guidelines for Human Stem Cell Research does not allow human cells to be injected into animals, nor for the breeding of animals using human eggs or sperm cells.

However, the organization has changed its mind and wants to investigate this field further.

Some of the researchers believe that the techniques could lead to breakthroughs in trying to tackle diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, while it could also be used to grow organs needed for human transplants.

"I am confident that these proposed changes will enable the NIH research community to move this promising area of science forward in a responsible manner," Carrie Wolinetz, NIH associate director for science policy, wrote in an article on the organization’s website.

Critics of the plan are worried that this could raise complex ethics questions and go beyond what is deemed acceptable in today’s society, especially when looking at altering an animal’s brain with human cells.

“Let's say that we have pigs with human brains and they are wondering why we are doing experiments on them,” New York Medical College researcher Stuart Newman told AFP.

“What if we had human bodies with animal brains, and then you say, ‘Well they are not really humans, we can do experiments on them and harvest organs from them’,” he observed. “I am coming up with extreme scenarios, but just making these chimeric embryos 15 or 20 years ago was considered an extreme scenario.”

Wolinetz says that adding human cells to animals is nothing new this technology has been used by those in the biomedical industry.

“Researchers have created and used animal models containing human cells for decades to gain valuable insights into human biology and disease development. For example, human tumor cells are routinely grown in mice to study cancer disease processes and to evaluate potential treatment strategies,” she wrote in the statement.

However, the proposal from the NIH is different, as this would involve human stem cells being injected into an animal embryo at a very early stage, which could theoretically mean that the human cells would contribute to the development on the animal.

Newman is adamant in his opposition, telling AFP this “is just a road that we should not go down.” While he accepts that the intention is not to create animals with fully functioning human brains, he adds that “we don't have any laws in this country that would stop doing those things.”

Some experts have spoken of the need to use human cells in animals to help find cures for diseases, which are baffling scientists. Robert Klitzman, director of Columbia University's Masters of bioethics program, believes the move taken by the NIH could potentially help millions of people around the world and was a “great step in the right direction.”

“If we want to do research on schizophrenia and Alzheimer's and depression, we can't readily do research on brain cells of humans with these diseases because we can't open up the brains of people while they are alive,” Klitzman told AFP.

However, despite championing the move, he has urged caution and said that ethics experts should be on the oversight committee.

“We need to be careful with human brain cells,” he said. “What we don't want is a mouse or a chimp that suddenly has human-like qualities, because morally that creates a number of problems.”