2nd anniversary of Michael Brown's death: What's changed?

On August 9, 2014, unarmed black teenager Michael Brown was fatally shot by white police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri. The killing sparked nationwide protests against police brutality and led to changes to policing practices.

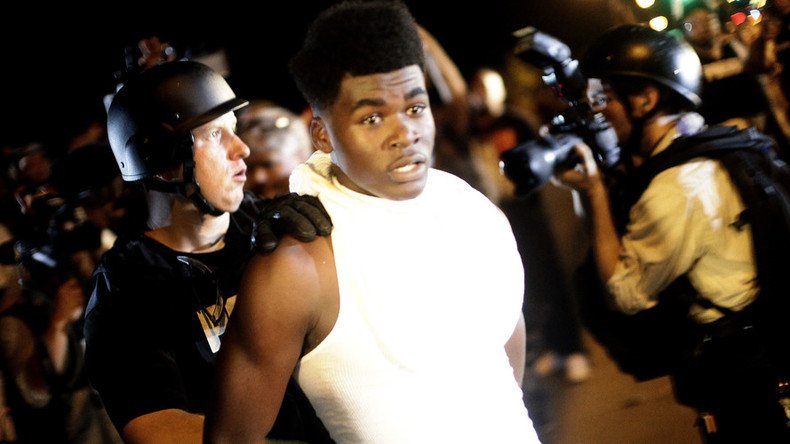

What came after Brown's death in the middle of Canfield Drive in a predominately black St. Louis suburb ‒ with a mostly white power structure ‒ could have played out in many US cities and towns: citizen riots, militarized government reaction, a grand jury exoneration of a police officer's decision to kill, and official denunciations from the highest levels of the federal government of a local legal system chocked full of provincial, classist, and racist inequalities.

Similar eruptions have occurred in Baltimore, Maryland; New York City; Cleveland, Ohio; Minneapolis, Minnesota; San Francisco, California; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; and beyond. Black lives were ended while police careers were largely maintained. The role of police in America, especially within marginalized communities, is at the center of a international debate that plays out everywhere from urban streets to cable news features.

But what has changed since August 9, 2014?

1. Black Lives Matter and protests of police immunity

If the acquittal of Trayvon Martin's killer, George Zimmerman, in 2013 planted the seed of the Black Lives Matter movement, Brown's death was the catalyst for the movement's primary growth. The movement is essentially a decentralized, social-media-driven effort to call attention to the effects, mostly on communities of color, of systemic racism, police brutality, and the exemption from punishment with which police officers have been given to act ‒ and kill ‒ in the name of the state.

Lauded, respected, reviled, ignored, and misunderstood, the movement has inspired and organized rallies and demonstrations to both react to and prevent police violence on a local level.

Police avoided federal civil rights charges in 96% of cases over 20 years - reporthttps://t.co/aNuUAQvaXbpic.twitter.com/vqjwI94jho

— RT America (@RT_America) March 15, 2016

In addition to protests following Brown's killing and a St. Louis County grand jury's decision not to indict Wilson, major demonstrations have sprung from the police murder of black men and women and the non-indictments of or lack of charges applied to police officers who killed them. They include Eric Garner in New York City; Ezell Ford in Los Angeles, California; Freddie Gray in Baltimore; Jamar Clark in Minneapolis; Tamir Rice in Cleveland; Walter Scott in South Carolina; Laquan McDonald and Paul O'Neal in Chicago, Illinois; Samuel DuBose in Cincinnati, Ohio; Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge; and the controversial suicide of Sandra Bland in a Texas jail, among others.

2. Body cameras and video releases

The call for the proliferation of police body cameras has been a major aspect of reform efforts that have sprung from Brown's death and Black Lives Matter in general. The widely divergent accounts of Brown's death ‒ from Wilson, Brown's friend Dorian Johnson, and witnesses of the incident ‒ show that mandatory recording of police encounters with the public could reduce ambiguity surrounding alleged incidents of police brutality or misconduct.

While major law enforcement agencies have endorsed and adopted body and dashboard cameras as a mode of transparency, the policies that guide the use of police cameras allow for police or government officials to control what is and is not released to the public. On a more basic level, the recent police killing of O'Neal in Chicago is an example of how officers can wear a body camera but still avoid capturing a potentially volatile incident.

In the age of smartphones, when an encounter with police can easily be recorded and even live-streamed on sites like YouTube or Facebook Live, police have less control over what is released to the public. The ability to immediately show a police encounter on the internet has pushed the debate over policing to new territory in which those unfamiliar with police brutality can witness how it can unfold.

Police, however, have allies in companies like Facebook, which has offered law enforcement the ability to largely dictate how the social media site handles posted video of controversial police encounters. In the case of Korryn Gaines, a young woman who uploaded to Facebook and Instagram video of her standoff with police in Baltimore County, Maryland earlier this month, the social media giant acquiesced to law enforcement requests. Gaines' Facebook account was temporarily deleted, as was her Instagram account. While the accounts have been restored, most of the videos she uploaded have not.

3. Every police shooting is news

Since Brown's killing, the rise of Black Lives Matter, and the lightning-fast pace of news in the age of social media, it is difficult for a controversial police shooting to go unnoticed. Furthermore, upon the realization that the FBI was not collecting comprehensive data of instances of fatal police encounters, activists and news media have picked up the slack. The Guardian and the Washington Post have begun tracking police killings in America, regardless of the circumstances of the deadly encounter. Killed By Police is another outlet for identifying officer-involved killings.

Since January 1, 2016, the Post has counted 579 police killings, The Guardian has tallied 647, while Killed By Police has 705 included in its database.

4. Police and official reaction

Law enforcement, government officials and their supporters in the US are not passive in the face of criticism and accusations of systemic racism. Many police departments have pledged to be more transparent via the use of body cameras, institution of officer misconduct policies, use of force reports, the heightening of training requirements, and, in places like Ferguson, a high turnover of top officials.

#BlackLivesMatter calls for slavery reparations, free education & justice reforms https://t.co/wRzOZU1v9npic.twitter.com/zvu6claDDS

— RT America (@RT_America) August 2, 2016

Yet a conciliatory attitude among officials is just one side of the coin. The other is entrenchment and demonization of calls for change. For example, in Missouri, the state legislature is controlled by conservatives unwilling to respond to basic police reform efforts. Meanwhile, the state's Republican primary for governor featured a roster of candidates seeking to out-do one another on just who would be most harsh in the face of further rioting in Ferguson or more demonstrations at the University of Missouri, where students incensed by Brown's killing and Wilson's non-indictment, as well as the history of marginalization black students have faced at the school, led to protests that brought down the university's president and chancellor.

In addition, Louisiana recently became the first state to enact a so-called 'Blue Lives Matter' law that makes attacking police a hate crime. New York is considering a similar law.

5. Killings of police

The events that have unfolded since August 9, 2014, have also included high-profile attacks on law enforcement. In July, a sniper opened fire on law enforcement agents patrolling a Black Lives Matter demonstration in Dallas, Texas, killing five officers and injuring others. The sniper, Micah Johnson, had expressed anger over the police killings of black Americans, as did Gavin Long, who traveled to Baton Rouge and killed three police officers just days after white police officers there pinned Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old black man, to the ground and fatally shot him.

There have been 34 firearms-related deaths of law enforcement officers in the US so far in 2016, according to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund. That's compared to 21 in 2015 through August 9. In the past decade, the years with the most officers fatally shot were 2011 (73) and 2007 (70).