Declassified justice: Gitmo lawyer explains CIA censorship of clients

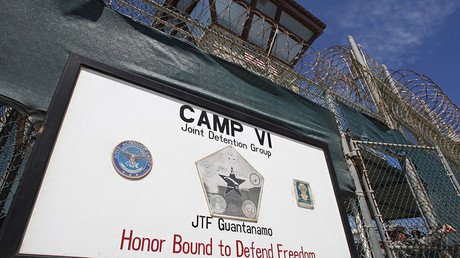

President Barack Obama’s recent release of 15 prisoners from Guantanamo Bay marked the largest single transfer yet. However, as the US loosens its clutches on some detainees, the CIA’s grip on keeping them silent remains tight as ever.

Despite a recent poll finding over half of US citizens believing the remaining 61 Guantanamo Bay prisoners should be either given a trial or released, their future is still murky. The truth is that their only hope for a fair trial is in the hands of an authority that needs to keep them silent.

James Connell, attorney for Gitmo detainee Ammar Al Baluchi, spoke with RT on the issues he faces with the CIA’s ability to classify the most basic information an attorney needs to build a case for his client. One problem is that the CIA is seemingly given free reign over what is and is not censored, through a process known as presumptive classification.

“Anything a detainee said at Guantanamo Bay was considered to be classified for a number of years,” Connell explained.

Connell’s client, Al Baluchi, is now declassified, but new documents demonstrate the extreme levels of censorship he and other attorneys faced.

“Classified information included details of detainees’ transfers, the nature of their detention, conditions of their confinement, their treatment and the names of people involved in the rendition detention,” Connell told RT.

Veracity had little to do with classification as much as subject matter.

“Allegations, even false allegations of torture or what they call false allegations of torture, which is especially interesting because the guidelines themselves contain a number of claims that we now know are false,” Connell told RT.

For example, one of the claims made was that there were never more than 100 prisoners held in the rendition detention interrogation program, “when the Senate’s committee confirmed that there were at least 119,” Connell explained.

But whether the act of classifying information was truly used out of necessity is debatable. Connell believes the extreme level of censorship “is just the opening move in a long series of attempts to control what the men at Guantanamo can reveal about their treatment.”

“There have been other things like recording devices found in the meeting rooms, where the attorneys meet with the defendants,” Connell continued, “and a long series of other issues which have interfered with the ability of those trials to make any progress and the ability of the men to get a fair trial.”

An even larger impediment on the ability for detainees to receive a fair trial is the possibility that discussions between the attorneys and clients was recorded, a likely violation of attorney client privileges.

He cannot claim to know who installed the devices and who was listening to their conversations, but “we know that the Department of Defense testified that they were responsible for maintaining the recording devices and after a hurricane came through, that they went back in and even repaired them,” he said, adding, “But who put them in there, we don’t know.”

Al Baluchi offers a very unique challenge as well. Al Baluchi was the inspiration for the interrogation scenes in the Academy Award-winning film, Zero Dark Thirty. The CIA helped the filmmakers by providing information to them, information that Connell still can’t get.

“We’re still fighting to find out the information that the CIA gave to the filmmakers of Zero Dark Thirty. That issue has been before the military commissions since 2012.”