‘Incarcerated Workers’ stage nationwide prison labor strike 45 years after 1971 Attica riot

On the 45th anniversary of the famous Attica riot, inmates across the US are attempting to bring attention to the dire circumstances that prison populations endure, in the country with the highest incarceration rate in the world, by going on strike.

September 9, 2016 marks 45 years since the prisoners in New York’s Attica Correctional Facility took over the prison to demand humane treatment. In the four-and-a-half decades since then, little has improved, according to those living behind bars.

Inmates are protesting a myriad of problems facing the incarcerated population, such as the low wages they receive for work they are required to do by penitentiaries that benefit the facilities themselves and private companies that contract out labor to prisons.

Some inmates’ grievances were outlined in a list of demands posted on the Industrial Workers of the World Incarcerated Workers’ Facebook page, containing complaints about the conditions prisoners in South Carolina face.

Included on the list of seemingly basic human rights was an end to free labor by prisoners in the Palmetto State, where private companies were criticized for using prisoners as skilled labor but paying them under $2 an hour.

In addition, prisoners demanded an opportunity for education and rehabilitation programs as well as an end to “the practice of in camera video doctor visits for medical and mental health concerns.”

The Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC), the organization behind the strike, referred to it as “a Call to Action Against Slavery in America.”

“We hope to end prison slavery by making it impossible, by refusing to be slaves any longer,” they explained.

The uprising at Attica 45 years ago made similar demands, as IWOC’s co-chair Azzurra Crispino explained to RT.

“Inmates in Attica were rioting for many of the same conditions that inmates are striking for today,” Crispino said, “an end to prison slavery, human dignity, adequate access to medical care, adequate access to wages.”

The last one is a big one. While inmates across the country are protesting many problems, such as being served moldy food or, such as in Texas, being confined to concrete cells with no air conditioning with temperatures reaching over 100 degrees (38 C), the labor issue by sheer volume is the most contentious.

There are over 900,000 inmates working out of the 2.4 million prisoners in the country.

In some states, calling the DMV means the person on the other end of the phone is an inmate, certain brands of underwear have been sewn by the incarcerated, and the cost of prison operations is offset by inmates who are tasked with keeping the facilities running by providing food, maintenance and labor. However, many of them will be lucky to receive even a dime for their work.

All inmates at Alabama’s William C. Holman Correctional Facility in Atmore refused to report to their jobs as part of the strike. A contact inside told Support Prisoner Resistance, “all inmates at Holman Prison refused to report to their prison jobs without incident. With the rising of the sun came an eerie silence as the men at Holman laid on their racks reading or sleeping. Officers are performing all tasks.”

However, with the fifth highest incarceration rate in the country, the Alabama Department of Corrections has a backup plan. Should the protest continue, inmates in a nearby work release facility will take over work at the tag plane, WNCF reported. The plant is “where all of the State’s motor vehicle tags are manufactured,” according to the prison’s website.

Slave labor in the US is banned under the Constitution’s Thirteenth Amendment, save for one clause: people who are “duly convicted” of a crime.

“The 13th Amendment of the Constitution, most people believe ended slavery but it didn’t,” Crispino told RT. “It just made people convicted of a crime to be made to work without pay.”

Alex Friedmann, managing editor of Prison Legal News and the associate director of the Human Rights Defense Center, told CBS News: “That’s why none of these protections, such as worker protections, apply to prisoners. So under the 13th Amendment, they’re basically worked as slaves, and if they don’t work, they’re punished.”

This is why wages for prisoners fall well below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, reaching bottoms of 15 cents an hour, while some states are allowed to not pay their prisoners at all. Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia and Texas are all allowed to force inmates to work for free, the Nation reported.

Meanwhile, large corporations, such as Victoria’s Secret or AT&T, are allowed to sell work contracts to state and federal prisons that outsource work to earn them billions of dollars. In addition, some states use prison work programs as means to make products for state use.

New York State’s Corcraft produces everything from lockers to uniforms for “government agencies (including other states).”

Prisoners communicating the only way they can. Brooklyn. #PrisonStrikepic.twitter.com/kQPjUZQG3O

— NYersAgainstBratton (@AGAINSTBRATTON) September 10, 2016

This is what has led prisoners across the country to participate in a national strike.

“We want to people to understand the economics of the prison system,” Melvin Brooks-Ray, founder of the Free Alabama Movement and former inmate, told Wired. “It’s not about crime and punishment. It’s about money.”

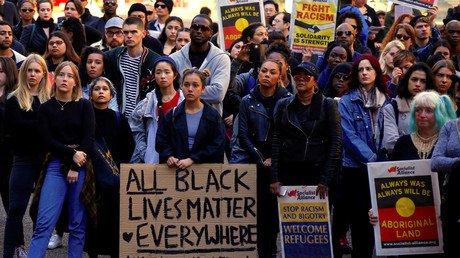

On Friday, protests across the country took place to show solidarity with the protesters behind bars.

"Tear that damn jail down right now!"#PrisonStrike Durham solidarity march blocking McDonald's entrance pic.twitter.com/3ypg8L8Wy0

— Eli Meyerhoff (@EliMeye) September 10, 2016

The full effect of the protests will not be known until later, but perhaps this will be one step closer to fixing the problems that persist in the country that holds 25 percent of the world’s incarcerated population.