Rape kit backlog results in lawsuits against police departments

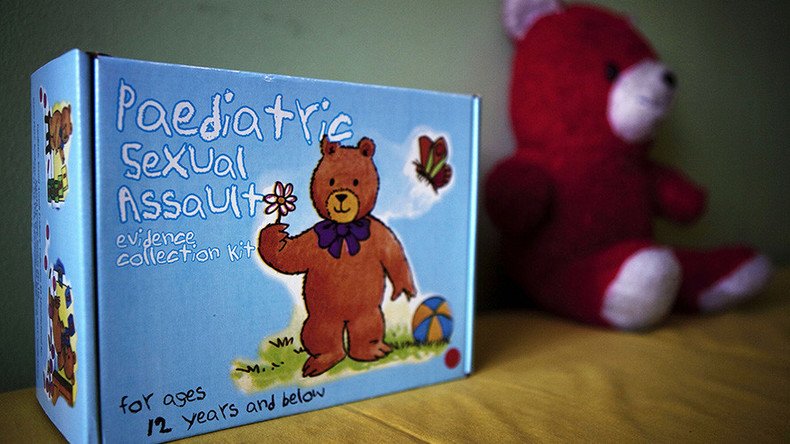

The backlog of evidence taken from the bodies of sexual assault victims after attacks is a national problem. But a San Francisco woman hopes to send a message to the police department that waited two years to test her kit by taking both the city and those who handled her case to court.

Heather Marlowe’s rape kit was one of an estimated 400,000 nationwide that went untested, according to the US Department of Justice. After having a rape kit collected after a 2010 sexual assault, it took two years for it to be tested and another four for her to learn that they had done so.

In fact, she was only informed that her kit lacked sufficient evidence when she sued the city of San Francisco, California along with the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) over mishandling the investigation in January. With that action, she became one of many frustrated women who are taking police departments to court over the low priority their claims are given.

Marlowe is suing the city, the president of the SFPD, the chief of police, the deputy chief of police and the officer that handled her case. She claims that the plaintiffs violated her right to due process and equal protection under both the US Constitution and the California Constitution.

The city argued that Marlowe cannot claim gender-based discrimination because there is no evidence that they handle rape kits collected from men any differently. Marlowe's attorney, Alexander Zalkin, is not concerned about this argument: "The statistics show that 90 percent of sexual or rape crimes are against women. When you take a step back, this is almost universally affecting women,” he told Vice.

In California, rape kits are legally required to be tested within 14 days of DNA collection and the information must be uploaded to the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Combined DNA Index System – or CODIS, a national database of offenders’ DNA.

While that might be the rule, it does not mean that it is always followed.

“The 14 days that it was supposed to take for my kit to be processed turned into 868 days," Marlowe told the San Francisco Police Commission during a meeting in 2013, Vice reported. "I got to a point where following up [and] trying to attain any information was becoming very frustrating and re-traumatizing, because I was continually being told that my kit was not a priority."

While this rule may help victims going forward, it has done little to ease the backlog of untested rape kits in San Francisco where some date back to the 1980s, according to a 2013 investigation by ABC Bay Area channel KGO.

Marlowe is far from the first victim to feel this frustration or to take legal action as a result. In 2014, three rape victims filed a lawsuit against the City of Memphis, Tennessee; Shelby County; police director Toney Armstrong; former director Larry Godwin; District Attorney Amy Weirich; and convicted rapist Anthony Alliano, among others.

The three victims ‒ Meaghan Ybos, Madison Graves and Rachel Johnson ‒ each had evidence from reported rapes collected and “transported to the City of Memphis, Shelby County and its agents for testing, evidentiary and custodial purposes,” the lawsuit claims.

However, in the years it took for the kits to actually be tested, “total spoilage or a significant degree of spoilage had likely occurred such that the submission of the evidence had been effectively rendered a nullity,” the lawsuit reads.

Ybos was 16-years-old when she was attacked by Alliano, but when she reported the crime immediately after the rape, she was met with disbelief: “The inquiries focused largely on her and presupposed the falsity of her story rather than on the particular facts relevant to the assault.”

In addition, she was also assured that her kit would be tested in a timely manner. This was the basis for her consenting to have evidence removed from her genital areas, as the lawsuit explains, “it was never contemplated nor imagined that said rape kit would be misplaced, discarded or otherwise forgotten about. No such disclaimer was made.”

Both Graves and Johnson received similar treatment from the police, and Alliano was only caught when he attempted to use a credit card he stole from Johnson after her attack.

The treatment these three women received from investigating officers is not restricted to Memphis. Marlowe told Vice that police told her that she "should not have been out partying with the rest of the city on the day she was drugged, kidnapped, and forcibly raped."

The Department of Justice (DOJ) found that police officers in Baltimore engaged in similar conversations with sexual assault victims, such as asking victims, “Why are you messing that guy’s life up?” according to their report on the Baltimore Police Department.

The report also notes Baltimore’s rape kit backlog, saying “BPD detectives request testing of rape kits in fewer than one in five of BPD’s adult sexual assault cases, leaving these rape kits to sit untested in BPD’s evidence collection unit.”

Last year, seven women in Harvey, Illinois settled a lawsuit against the city that claimed it had spent years mishandling sexual assault cases. Arguing that the Chicago suburb had violated their civil rights as women, six of the women received $241,250. One woman received $1.2 million after the department was found to have egregiously mishandled her case. Due to the department’s errors, the stepdaughter of a Cook County correctional officer was molested for years, according to The Chicago Tribune.

Many of Harvey’s sexual assault cases were not solved until Cook County prosecutors seized evidence from Harvey and tested it themselves.

The need for rape kit testing was highlighted in a 2016 study that examined 900 untested rape kits from Detroit, Michigan and found 259 CODIS profile matches, 69 of whom were serial rapists.

Those numbers were not a fluke. A 2015 study from The Detroit Sexual Assault Kit (SAK) Action Research Project (ARP) tested 1,595 kits in Detroit, and found that almost half of them had CODIS eligible profiles, 28 percent were linked to already existing CODIS profiles and 8 percent of the tests examined matched serial sexual assaults.

While numerous women find it necessary to battle police departments and local governments in court, the DOJ announced on Monday that it would allocate over $38 million to testing preexisting sexual assault kits.

They will have their work cut out for them. On Thursday, Montana Attorney General Tim Fox announced that the Big Sky State will begin testing 1,400 rape kits that date back to 1994.