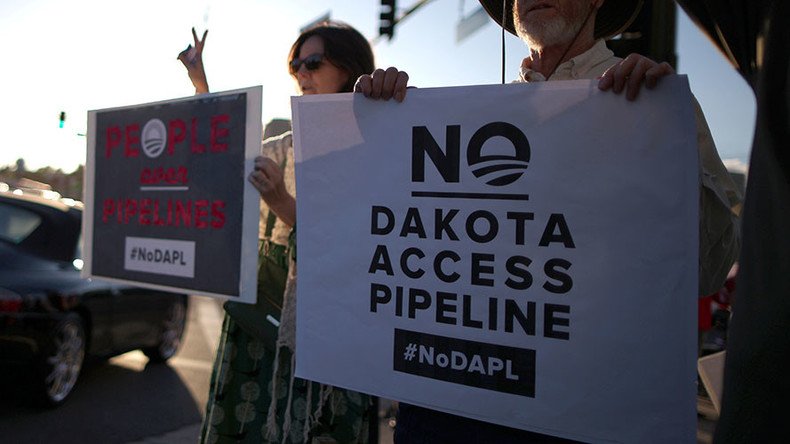

There are no plans to evict a Dakota Access Pipeline protest camp on land belonging to the US Army Corps of Engineers, federal officials said. The camp in North Dakota was set up without federal permission, but a Native American tribe claims the land.

The protest site – known as the Oceti Sakowin, or Seven Council Fires camp – is located near the confluence of the Missouri and Cannonball rivers, and sprang up as overflow from other campsites in the area. Native American tribes and their supporters have set up the protest camps in an effort to halt construction of the $3.78 billion, four-state Dakota Access Pipeline (DAP).

The Army Corps of Engineers said it is "encouraging" protesters at the permitless camp to relocate to permitted areas.

"We don't have the physical ability to go out and evict people – it gives the appearance of not protecting free speech," said Eileen Williamson, a Corps spokeswoman. "Our hands are really tied."

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe "never ceded" the land in question and plans to stay throughout the winter if need be, according to camp spokesman Cody Hall of South Dakota's Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe.

"We're not leaving until we defeat this big black snake," Hall said of the 1,172-mile pipeline, according to AP.

The pipeline was first opposed by the Standing Rock Sioux for its planned route underneath the Missouri River, which the tribe said would potentially damage its drinking water and irrigation.

The Standing Rock Sioux have also claimed that construction, led by the Dallas-based Energy Transfer Partners, has desecrated several areas of "significant cultural and historic value" to the tribe. In late August,the tribe requested a temporary injunction to halt construction, yet a federal judge denied the request weeks later. Energy Transfer Partners recently bought ranch land that tribal officials say is the site of Sioux artifacts destroyed by pipeline crews, further complicating tensions among protesters, building crews and security officers, locals, and law enforcement.

North Dakota's lone congressman, Republican Kevin Cramer, said he was concerned about "the illegal activity that may be orchestrated" from the camp to interfere with pipeline construction.

"If that camp was full of people advocating for fossil fuels, they would have been removed by now," said Cramer, who has clashed with Native American activists in the past. "There is some discretionary enforcement going on."

The camp promotes "peaceful" resistance, according to Hall, the Sioux spokesman. About 95 people have been arrested at area pipeline protests since early August, but none at the camp itself, AP reported. On Wednesday, heavily armed police arrested 22 people for criminal trespass on private property, possession of stolen property, and resisting arrest amid a gathering of prayer.

"People don't leave from the camp with malicious intent to do harm," Hall said. "There are always going to be a few bad eggs in any group you can't get the message to."

On September 9, the Obama administration halted construction within 20 miles on either side of Lake Oahe, a Missouri River reservoir, following objection to construction by the Standing Rock Sioux. While the project has been cleared by all relevant federal agencies, the Standing Rock have said they were not consulted, claiming pipeline construction crosses through lands that hold burial and cultural artifacts sacred to the tribe yet outside its reservation.

The government has not revealed when that delay will be lifted, and recently released plans for a series of meetings with American tribal leaders to discuss "infrastructure projects" and "timely and meaningful tribal input," according to the Dallas Morning News.

The five meetings scheduled through November 21 were described as "consultations on how the Federal Government can better account for, and integrate tribal views, on future infrastructure decisions throughout the country," the Morning News reported.

If completed, the pipeline would travel across four states and is expected to carry nearly half-million barrels of crude oil daily from the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota. The pipeline would travel through North and South Dakota, under the Missouri River, through Iowa to an existing pipeline in Illinois.

Energy Transfer Partners originally planned to complete the project in November, and has argued in court filings that a construction stoppage would cost $1.4 billion in lost revenue over the first year.

Last week, US House Democrats called for a complete review of the pipeline permitting process following a hearing on Capitol Hill. Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D-Arizona) said the pipeline permits approved by the US Army Corps of Engineers did not comply with legal requirements.

"The agencies involved in this decision-making process in Standing Rock, they made a mistake. A big mistake," Grijalva said, according to Indian Country Today Media Network. "They were disrespectful, paternalistic and kowtowing to some big money special interests in moving forward with this project. They have to correct that. And they have to correct it in a respectful, meaningful way."