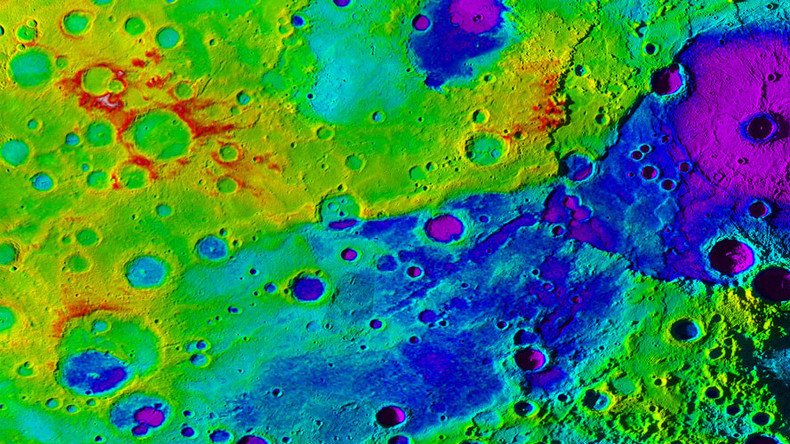

Shrinking planet: Discovery of Mercury’s ‘great valley’ indicates global contraction

The discovery of a broad valley on our solar system’s smallest planet suggests more evidence that Mercury is indeed shrinking, according to NASA.

Images taken from the space agency’s MESSENGER spacecraft reveal a valley more than 1,000km (620 miles) long and extending into the Rembrandt basin – one of the largest and youngest impact basins on the planet.

The valley is about 400km wide and 3km deep, according to NASA.

“Unlike Earth’s Great Rift Valley, Mercury’s great valley is not caused by the pulling apart of lithospheric plates due to plate tectonics; it is the result of the global contraction of a shrinking one-plate planet,” said Tom Watters, senior scientist at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and lead author of a study about Mercury published in Geophysical Research Letters.

Roundest-ever natural object found 5,000 light years away https://t.co/tx5TimpRS5

— RT (@RT_com) November 17, 2016

The study determined the most likely explanation for the valley is the collapse of Mercury’s crust and upper mantle due to the planet’s contraction. Rocks in the crust are thrust upward, while an emerging valley floor sags downward where the forces of contraction are greatest.

While similar geological processes occur on Earth, they do not have the same effect on our planet because, unlike single-plate Mercury, Earth boasts multiple tectonic plates and the shrinking of one does not affect the others.

The newly discovered valley is bound by two large fault ‘scarps’ – cliff-like land structures that resemble stairs. Scientists say these formed as Mercury’s interior cooled and contracted.

Previous research published in October’s issue of Nature Geoscience confirmed Mercury was a tectonically active planet, just like Earth, and was shrinking. Researchers found small scarps and confirmed from their size they were very young and the planet’s plate was still active.

READ MORE:Mercury still has earthquakes and shrinks by the day - NASA

It had been accepted that such activity was in Mercury’s distant past and that Earth was the only planet in our solar system still tectonically active.