Illinois residents forced to cough up nearly $725mn in civil asset forfeitures

Over the course of a decade, Illinois and federal law enforcement took in more than $319 million and $404 million, respectively, from state residents who were merely suspected of having committed a crime, a new report has found.

“[E]very year, Illinois law enforcement agencies take tens of millions of dollars in cash, vehicles, land and other assets from state residents – in some cases without bringing criminal charges, let alone obtaining convictions, against property owners,” the Illinois chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU-IL) and the Illinois Policy Institute (IPI) jointly wrote in the introduction to a report outlining how much money law enforcement has made off of civil asset forfeitures since 2005.

Illinois law enforcement averaged approximately $31 million in confiscation a year on the state level between 2005 and 2014. Some asset seizures were never reported, the report found. The federal government averaged more than $36 million in asset forfeiture.

In 2012 alone, Illinois took in almost $20 million through asset forfeitures, ranking it the third worst state for its residents that year, according to a 2015 Institute for Justice report, a finding the ACLU-IL and IPI reiterated.

“Illinois stands out among other states for its high seizure rates, ranking among the top 11 in takings through equitable sharing with the federal government,” the authors wrote.

Civil asset forfeiture in Illinois is problematic for several reasons, according to the report. First, such litigation is against the property suspected of being involved in an illegal activity, not the person. Second, the law provides little protection for property owners, as they need never be arrested, charged or convicted of a crime to have their assets permanently seized. Third, property owners have no right to appointed legal counsel during a forfeiture proceeding. Fourth, the burden of proof in such cases is on the property owner “to prove that the property should not be permanently forfeited to the government – if he or she can afford to challenge the taking at all.” The prosecutor can admit hearsay into evidence in forfeiture cases, but property owners cannot.

On top of that, law enforcement agencies at all levels have “a strong financial incentive to seize property, because they reap almost all of the proceeds from civil asset forfeiture,” the report said.

The authors ‒ Ben Ruddell, criminal justice policy attorney at the ACLU, and Bryant Jackson-Green, a former criminal justice policy analyst at IPI ‒ outlined an example of civil asset forfeiture in Illinois that they described as “egregious.”

Last August, Judy Wiese, 70, allowed her grandson to borrow her 2009 Jeep Compass to drive to work. Although he had told her that he had fulfilled all of his legal obligations that had resulted from a driving under the influence (DUI) charge, his license was actually still suspended. That night, the grandson was arrested and the vehicle seized as an asset forfeiture.

“For more than five months, Wiese pleaded for the return of her vehicle and tried in vain to complete the legal paperwork required to contest the attempted forfeiture. During this time, without transportation, she was unable to attend therapy appointments for her broken arm, or even to make trips to the grocery store without help from friends,” the authors wrote.

Once a prosecutor meets the burden of proving that the property was involved in a crime, the owner must “somehow ‘prove a negative’,” and convince the court not only that he or she didn’t commit a crime, but that he or she “did not know and could not have known about the crime.” The owner isn’t off the hook even if he or she does manage to prove the negative, however, as the owner will still be responsible for 10 percent of the bond posted in order to have the case heard in court. Attorney’s fees cannot be recovered, either, for those cases when a property owner can afford to hire a lawyer.

“Illinois laws shouldn’t let the government permanently take property from a person who has never been convicted or even charged with a crime.” Ted Dabrowski, vice president of policy at IPI, said in a statement. “Innocent people shouldn’t have to live under the fear of this system. It’s not fair.”

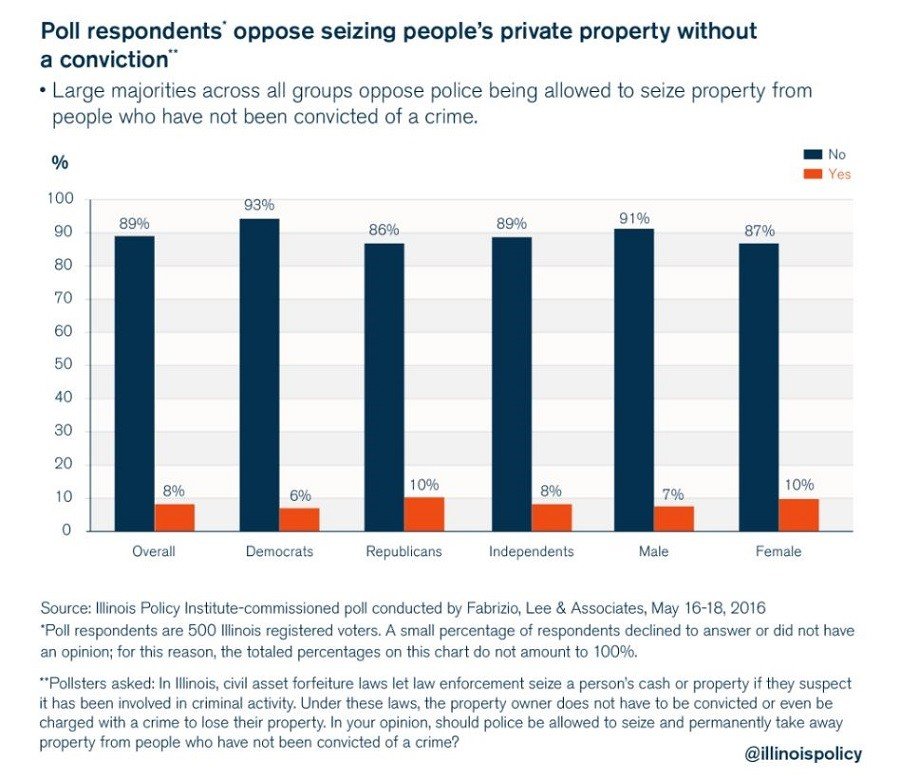

Ruddell and Jackson-Green called on Illinois to institute policy reforms in three areas to better protect innocent property owners: Require a criminal conviction before assets can be forfeited, and other “fair legal standards and procedures”; require forfeited assets to be auctioned off with the money going into a general revenue fund overseen by the General Assembly to remove incentives to engage in “policing for profit”; and require law enforcement agencies and prosecutors’ offices to be transparent about how much property is seized, where and when it was seized, the outcome of the cases and how the proceeds from forfeitures are spent.

“Asset forfeiture in Illinois has become policing for profit,” Ruddell said. “Without meaningful reform that insures transparency, this system will continue to take millions of dollars in property from people without true justice.”

“This report should serve as a wake-up call for all legislators who have not been aware that this system is operating in this fashion,” he added.

Any attempt to change Illinois’ asset forfeitures program will be met by steep opposition from law enforcement, however. The forfeited property helps take away the “fuel” driving street gang violence because “many times these people show up for court,” Lockport Police Chief Gary Lemming told WBBM. It also allows his department to buy one or two new squad cars each year.