Report on ‘Russian hacking’ offers disclaimers, barely mentions Russia

As the White House and Treasury Department announced new sanctions against Russia over the alleged hacking of US elections, the FBI and Homeland Security released a report that offered supposed proof amid an abundance of disclaimers.

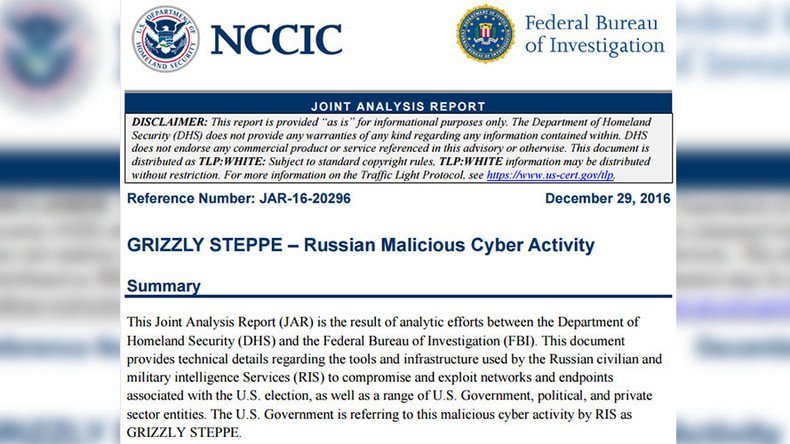

Given the incongruous name of “Grizzly Steppe,” the Joint Analysis Report (JAR) on “Russian malicious cyber activity” issued by the FBI and the DHS National Cybersecurity & Communications Integration Center (NCCIC) on Thursday begins with the following disclaimer:

“The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) does not provide any warranties of any kind regarding any information contained within.”

Obama's Russia sanctions: Note that the 'hacking' report released today:

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) December 29, 2016

1) Doesn't mention WikiLeaks

2) Has the following disclaimer: pic.twitter.com/fu4QbRlcyB

Accompanying the report was a joint statement by the FBI, Department of Homeland Security and the Director of National Intelligence, explaining that the “activity by Russian intelligence services is part of a decade-long campaign of cyber-enabled operations directed at the US government and its citizens.”

Joint statement by ODNI, DHS, and FBI on today's JAR. pic.twitter.com/FNJetlJ9F1

— Eric Geller (@ericgeller) December 29, 2016

The actual words “Russia” and “Russian” are mentioned only three times, with just 11 instances of “RIS” – a custom, catch-all acronym standing for “Russian Intelligence Services” without naming any. Both the FSB – Russia’s equivalent of the FBI – and the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence, were put on the US sanctions list on Thursday.

“The US Government confirms that two different RIS actors participated in the intrusion into a US political party,” says the JAR, identifying the two as APT28 and APT29. There is no indication anywhere in the document that these two groups are in any way connected with the Russian intelligence services, however.

GRIZZLY STEPPE only restates premise that APT 28/29 are Russian gov, rather than proving it. let’s hope for more in congressional testimony

— Sam Biddle (@samfbiddle) December 29, 2016

Even when detailing the efforts of the two purported hacker groups, the report uses vague and noncommittal language. For example, the actual political party allegedly hacked by the two groups is never identified:

“In summer 2015, an APT29 spearphishing campaign directed emails containing a malicious link to over 1,000 recipients… In the course of that campaign, APT29 successfully compromised a US political party.”

“In spring 2016, APT28 compromised the same political party,” the report continues. “Using the harvested credentials, APT28 was able to gain access and steal content, likely leading to the exfiltration of information from multiple senior party members. The US Government assesses that information was leaked to the press and publicly disclosed.”

This could be referring to emails and documents of the Democratic National Committee, which were made public by Guccifer 2.0 and WikiLeaks – both of whom have categorically rejected any claim of Russian hackers being responsible. It could also refer to WikiLeaks publishing emails from the private account of Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman John Podesta, over the course of a month prior to the November 8 election. The JAR does not actually say so, however.

Nor does the JAR note anywhere that it was CrowdStrike, a cybersecurity company hired by the DNC to investigate the June 2016 data breach, that accused APT28 and APT29 – which they named “Cozy Bear” and “Fancy Bear” – of being Russian government entities. CrowdStrike has never offered any proof for this assertion, which the JAR merely repeats without attribution.

Any antivirus company doing any amount of threat intelligence would be able to come up with more solid indicators than FBI released.

— Jonathan Zdziarski (@JZdziarski) December 29, 2016

In addition to CozyBear and FancyBear, the 13-page report includes a list of more ridiculous names for alleged Russian hacker groups, such as CakeDuke, CrouchingYeti, Energetic Bear, EVILTOSS, OLDBAIT, and SEADADDY.

The second half of the report is focused on mitigation strategies, from backing up one’s data and changing passwords to information-sharing with the government and giving Homeland Security access to networks for “voluntary assessments” of vulnerabilities.

An appendix to the report lists hundreds of IP addresses and code the authors say are “used by Russian civilian and military intelligence services.” While some of the addresses are in Russia, others are in the US, and none of the data actually points to Russian involvement.