US hurricanes: Causes, trends & what the future holds (VIDEO)

Atlantic hurricane season has reached its peak and as Florida deals with devastation wrought by Irma, RT takes a look at where the phenomena come from and if they are really becoming more frequent?

The 2017 hurricane season has already seen Texas rocked by Harvey and Florida battered by Irma, and there are concerns that Jose, which is currently lashing the Caribbean, could hit the US east coast.

While September is the most active month for hurricanes worldwide, the North Atlantic hurricane season is set to continue until November 30, raising the question – where are these monster storms originating?

READ MORE: 4 dead as Hurricane Irma rocks Florida, leaving 3.5mn without power (PHOTOS, VIDEOS)

Cape Verde Islands

Most of the major hurricanes that have impacted the US originated in Cape Verde – a nation on a volcanic archipelago off the northwest coast of Africa – according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

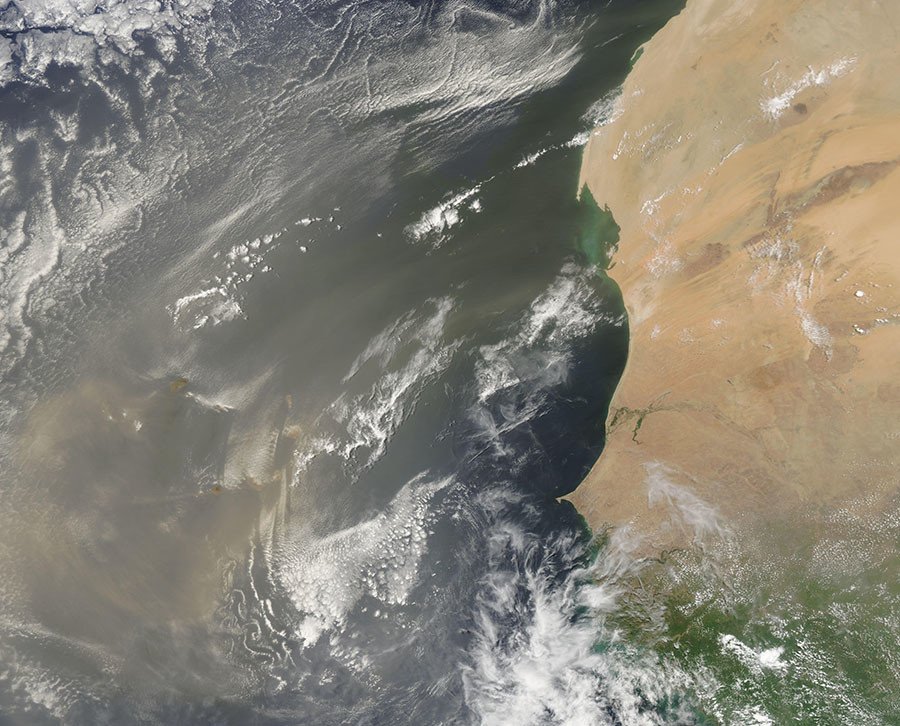

The interaction between the hot dry air of the Sahara Desert and the cooler, more humid air from the Gulf of Guinea below creates high-altitude winds known as the African Easterly Jet.

Blowing from east to west across Africa, the winds form clusters of thunderstorms once the waves of air have enough moisture, lift, and instability.

The storms typically form every two to three days in a region near Cape Verde, but it is not until the period between summer and autumn that conditions become favorable for the development of tropical cyclones.

‘Tropical waves’ of air interact with the warm equatorial water of the Atlantic as they head west, prompting columns of warm moist air to rise from the ocean and create an ideal environment to develop into a full-blown hurricane.

However, if the Saharan Air Layer, commonly known as Saharan dust, is in the vicinity at the time it can weaken tropical cyclones over the Atlantic.

This very dry air is most likely to have an impact in July and early August, Dr Gerry Bell, a hurricane climate specialist with NOAA told RT.com. This is when atmospheric conditions are only marginally conducive, if at all, for tropical storm formation.

Hurricane Sandy and Hurricane Andrew began life as tropical waves off the coast of west Africa.

Five of the worst hurricanes to ever hit the US (PHOTOS) https://t.co/Fk0s82dSVA#Katrina#Sandy#Ike#Andrew#Wilmahttps://t.co/Fk0s82dSVApic.twitter.com/JJeiVTMcKX

— RT America (@RT_America) September 10, 2017

Irma was first spotted as a tropical disturbance off the Cape Verde Islands in late August, before becoming a hurricane over the Atlantic as it moved west.

Cape Verde hurricanes are known for being particularly large and intense, however not all hurricanes hitting the US originate here: Harvey evolved from a tropical wave to the east of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean Sea.

A 2015 study examining the relationship between West African tropical disturbances and Atlantic hurricanes found that the larger an area covered by the disturbances was, the more likely it would develop into a hurricane only one to two weeks later.

Is the US getting hit more frequently by hurricanes?

Hurricane seasons have generally been longer since 1995, according to Bell, which he says is consistent with a high activity era.

The season lengths since 1995 are comparable to those during the last active era of the 1950s-1960s.

A study published in Nature last year, led by James Elsner, a climate scientist and geographer at Florida State University, found that, while hurricanes were becoming more powerful, they were also becoming less frequent.

However, there appears to be little consensus among scientific researchers.

An early draft of the government publication, the US Climate Science Special Report, published by the New York Times notes an “observed upward trend in North Atlantic hurricane activity since the 1970s.”

The NOAA Geophysical fluid dynamics laboratory, meanwhile, says it is too early to conclude that global warming has already had a “detectable impact on Atlantic hurricane or global tropical cyclone activity.” However, expects it to result in more intense tropical cyclones globally with substantially higher rainfall rates by the end of the 21st century.

It notes, however, that there is little evidence to suggest that climate change will lead to a large increase in numbers of tropical storms or overall hurricanes in the Atlantic.