'They were hanging effigies’: Little Rock 9 activist recalls hate campaign to block desegregation

Minnijean Brown-Trickey will walk up to the doors of Little Rock Central High celebrating a victory this week, almost 60 years to the day since she was first set upon, spat at and terrorized by a white mob for enrolling at the former all-white school in Arkansas.

Now an activist and non-violence mentor for children, the 75 year old will commemorate a group of black students who famously held firm in a battle to integrate US schools.

The pupils became known as the Little Rock Nine, with Brown, Melba Beals, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Gloria Karlmark, Carlotta LaNier, Thelma Mothershed, Terrence Roberts, and Jefferson Thomas a target for those seeking to maintain the segregated status quo in Arkansas.

The episode saw local Governor Orval Faubus garner international coverage for flouting federal law as he used the Arkansas National Guard, under the guise of a peacekeeping force, to block the nine students from school grounds.

The crisis escalated over the course of September 1957 until members of an elite infantry division were called into the city when, to paraphrase President Dwight D Eisenhower, the local government failed to eliminate violent opposition.

Minnijean Brown

Growing up in 1940s Arkansas, where public transport, restaurants and drinking fountains were segregated by skin color, Brown was acutely aware of the unfair society in which she lived. However, Brown tells RT.com that it wasn’t until her first day at Little Rock Central High School that she experienced mass, vitriolic hatred.

“In my family there was a great effort to protect me from individual prejudice. But you can’t be protected from institutional oppression,” she explained.

“I really thought that going to Central High was going to be simple. I thought it was going to be fun, and to walk into this mob, well you just get your heart broken and it never heals. You’re just so shocked.”

What transpired was a litmus test for a new era in US education, brought about by grassroots activism and the 1954 US Supreme Court ruling in Brown v Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas which determined that racially divided schooling was unconstitutional and “inherently unequal.”

In the book ‘Little Rock: Race and Resistance at Central High School,’ Karen Anderson wrote how in Arkansas, African American schools were reliant on support from outside philanthropists such as Julius Rosenwald. The white Central High School, meanwhile, received full funding to the tune of $1.5 million from the state.

White riots

Up until the morning of September 4, 1957, Brown had been more concerned about what she would wear to class, than the thought of crossing a racial divide. But, on arriving at the school, she and the others were met by adults and children screaming for them to be lynched.

“Even though we lived in a segregated society and things were denied us, we were still brainwashed by the thought of the United States being the best place in the world. We said all those pledges and anthems. Brainwashing is some very powerful stuff, so it made it even more shocking because in my 15-year-old innocence I couldn’t imagine this happening,” she said.

“My mother said I was just worried about what I was going to wear the first day and getting new shoes. I was feeling excited.

"The Arkansas National Guard had all the streets blocked off and a perimeter around the whole school. I think five of us walked up together. It sounded like a sports event, a large number of people screaming, but they were screaming hatred like ‘kill them.’”

The incident made headlines throughout America, and produced the infamous image of white bigotry – student Hazel Bryan shouting abuse from behind Elizabeth Eckford.

The front page #OTD in 1957. Nine black students stopped from entering Little Rock Central High School. #nytimespic.twitter.com/yx2RC7YxhV

— New York Times OTD (@OnThisDayNYT) September 5, 2016

“When I see those pictures I think they gave away their dignity and it landed on us because we were just standing there looking pretty bewildered. We were shaking in our boots,” Brown told RT.com.

Caught between a ring of guardsmen and an increasingly angry pack of segregationists, the children had to abandon their efforts. But she says the hatred succeeded only in making her more determined to go to school.

“What the guards would do was when a white kid came up they opened and let them in. But they completely stopped us. When I have to think about it it triggers me to this day."

She adds: “I was going to go to school no matter what because when you see people behaving like that you say: ‘You’re not going to stop me… you’re not going to stop me with your brutality.”

‘Berserk’ mob

On September 23, the students actually made it inside the school through a side entrance only to be evacuated before lunchtime, when a 1,000-strong mob gathered on the school grounds.

“They were hanging effigies and they kicked and beat this black reporter,” said Brown.

“We were in there about an hour and a half when we were told that we had to leave for our safety. We had to go to an underground area where we got into two police cars. They told use to put our heads down and don’t look up. The drivers were told ‘once you start, do not stop’.

“I think the most interesting thing I can say about that day was the driver of my car had a gun and a billy club – he was a cop – and his hands were shaking.”

Infantry spring to action

Worldwide coverage of the trouble forced the hand of US President Dwight D Eisenhower, who ordered the 101st Airborne Division to disperse “demagogic extremists” and end interference at the school.

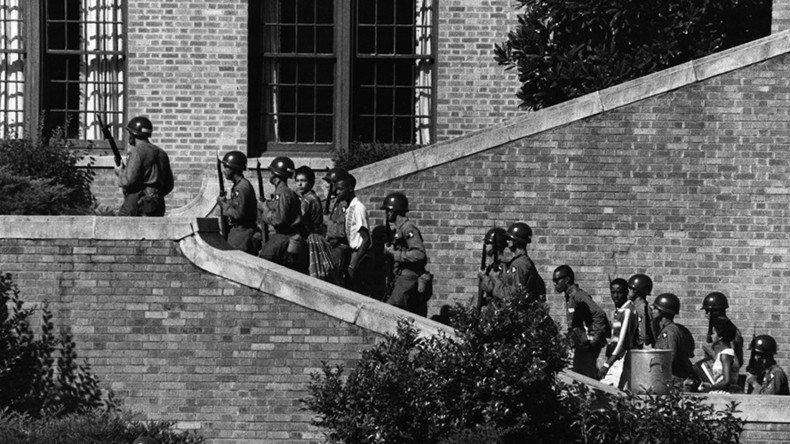

On September 25, 1957, the Little Rock Nine would enter through the front door of Central High surrounded by uniformed soldiers carrying rifles and bayonets. The group’s ordeal was only just beginning, however, as they would be subjected to torrents of abuse throughout the year.

Brown believes integration was designed to fail in Arkansas, given only nine black students were part of the process and that she herself was eventually expelled in February 1957 for calling a female student, who had thrown a purse filled with metal locks at her head, ‘white trash.’

“It really wasn’t supposed to happen the way it did. I think everyone thought that we would be scared away and we wouldn’t continue.

“All I did was learn how to survive in that horrific circumstance. But we did and I’m so proud of us for that.”