Why Flynn’s plea is a dead end for ‘Russiagate’ conspiracy

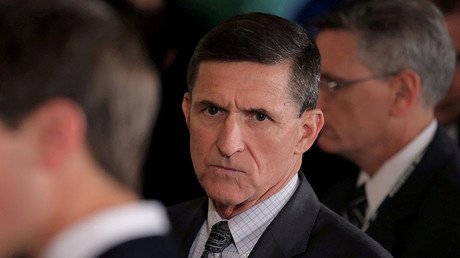

President Donald Trump’s short-lived national security adviser, Michael Flynn, pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI. Most US media jumped on the plea as proof of Trump’s collusion with Russia. Actual documents, however, tell a different story.

A court document signed by special counsel Robert Mueller, dated Thursday, specifies two instances of Flynn telling FBI investigators things that were not true. They relate to two conversations he had with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak, in December 2016.

In the Statement of Offense signed by Flynn at his court appearance on Friday, he admitted to acting on instructions from a senior “Presidential Transition Team” (PTT) official, prompting breathless speculation if that was Trump himself, his son-in-law Jared Kushner, or someone else altogether. The one question nobody seems to be asking is, “So what?”

Flynn's misleading of the FBI seems to stem from the Logan act. Well after the election, on Dec 29. Flynn tried to convince Russia to hold off expelling US diplomats & to not support a UN vote against Israel. His job--but also a potential Logan violation. https://t.co/4sNe5Dpq6lpic.twitter.com/hOjEYC1dHE

— Julian Assange 🔹 (@JulianAssange) December 1, 2017

It is intuitively obvious to even the most casual observer that Flynn’s “crime” is a procedural one: he told FBI investigators he hadn’t done a thing that he actually did. But was the thing he did - namely, speak with the Russian ambassador to the US - against the law? Not really.

Under the 1799 Logan Act, it is technically against the law for a private US citizen to engage in diplomacy. However, only two people have ever been indicted under that law, and no one has ever been prosecuted. Flynn was a member of the presidential transition team whose duties involved contacts with foreign diplomats. So why would the FBI even ask him about his contacts with Ambassador Kislyak?

“There was nothing wrong with the incoming national security adviser’s having meetings with foreign counterparts or discussing such matters as the sanctions in those meetings,” Andrew McCarthy of National Review wrote on Friday.

Because Flynn was “generally despised by Obama administration officials,” McCarthy added, “there has always been cynical suspicion that the decision to interview him was driven by the expectation that he would provide the FBI with an account inconsistent with the recorded conversation - i.e., that Flynn was being set up for prosecution on a process crime.”

Back in May, former deputy Attorney General Sally Yates testified before the Senate Judiciary subcommittee that she came to the White House on January 26 - two days after Flynn’s FBI interview - to say that he had lied about his conversations with Kislyak. How did she know? That, she said, was “based on classified information.”

Clearly, Yates knew Flynn was lying about the conversations because US intelligence had been listening in on them. An Obama administration official leaked that information to the Washington Post’s David Ignatius, who reported on the Flynn-Kislyak conversation on January 12, eight days before Trump’s inauguration.

Responding to that report, Vice President Pence said that Flynn’s conversation with Kislyak “had nothing whatsoever to do” with the Obama administration’s expulsion of Russian diplomats and closure of two diplomatic properties, enacted on December 29, 2016.

After the Post reported that the two did in fact discuss Obama’s sanctions, citing anonymous sources again, Flynn submitted his resignation.

So what "crime" was the FBI investigating? Violation of the absurd "Logan Act"? No one has been prosecuted under that in 200 years. Much more likely: The FBI was seeking to entrap Flynn into lying. The FBI itself triggered the "crime."

— George Szamuely (@GeorgeSzamuely) December 1, 2017

The dark undertone of the Post’s reporting was that Flynn was somehow “subverting” Obama’s sanctions, intended as punishment for - alleged, and to this day unproven - Russian “meddling” in US elections. What Flynn actually did, as documented by the special counsel, was to ask Russia not to escalate in response to Obama’s actions.

It worked, too: Russian President Vladimir Putin announced that Moscow would not expel any US diplomats, but rather invite them to the Kremlin for holiday celebrations. It wasn’t until July, after the passage of an anti-Russian bill in Congress, that Putin ordered the US to downsize its diplomatic staff in Russia by 755.

Grand irony: the underlying action that Flynn now admits he lied to the FBI about was urging de-escalation with a nuclear power, which is now no longer permissible pic.twitter.com/Vh4Nxz0nWK

— Michael Tracey (@mtracey) December 1, 2017

So the country that influenced US policy through Michael Flynn is Israel, not Russia. But Flynn did try to influence Russia, not the other way around. Ha-ha. This is the smoking gun? What a farce. https://t.co/VLw3wOLCCGpic.twitter.com/cZ3JBUxd4s

— Yasha Levine (@yashalevine) December 1, 2017

So what about the frantic insistence of “Russiagate” partisans that Flynn’s plea practically portends the downfall of the president they refuse to accept as legitimate? Their elation is unwarranted and premature, warns McCarthy. If a prosecutor has a cooperating witness who is an accomplice in a criminal scheme, the plea is structured so it proves the existence of the scheme.

“That is not happening in Flynn’s situation. Instead, like Papadopoulos, he is being permitted to plead guilty to a mere process crime,” he wrote, referring to a volunteer Trump campaign adviser who likewise pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about seeking contacts with (a nonexistent) “Putin’s niece.”

Flynn’s plea did include an admission he failed to report activities undertaken on behalf of a foreign government: Turkey, a key NATO ally of the US.

Nebojsa Malic for RT