My Lai massacre: The day US military slaughtered a village & tried to cover it up (GRAPHIC VIDEO)

Fifty years ago, a platoon of US soldiers stormed the quiet hamlet of My Lai in South Vietnam, unleashing a barrage of gunfire, grenades and sexual assault which left as many as 500 dead.

On March 16, 1968 an army unit entered My Lai. The troops were ordered to lay waste to anything “walking, crawling or growing” on a search and destroy mission that lasted four hours and left the village razed to the ground. Not even crops or livestock were spared. The atrocities of My Lai would remain largely hidden for 20 months, until vivid images and accounts of the massacre appeared in newspapers, shocking Americans and sparking massive anti-war protests.

THE MY LAI MASSACRE

US Infantry battalion Charlie Company entered the area under the erroneous understanding that Viet Cong guerrilla fighters were present. Instead, they found unarmed civilians, many of whom were children, women and the elderly.

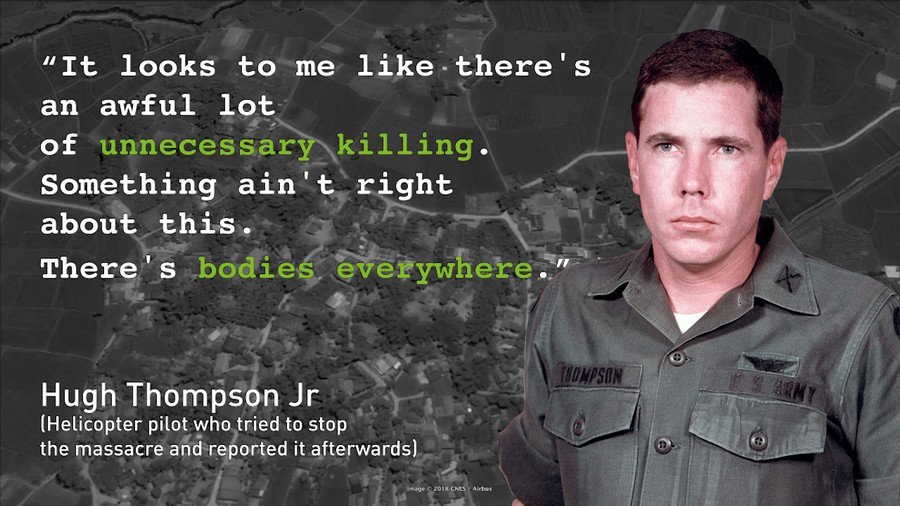

Unleashing a hail of firepower from M-16s and an M79 grenade launcher, the soldiers rounded up villagers and killed them, not before sexually assaulting as many as 20 women and teenagers. The horror only began to die down when army helicopter pilot Hugh Thompson Jr landed between the soldiers and the villagers, threatening to fire at the troops.

“The whole thing was so deliberate. It was point-blank murder and I was standing there watching it,” Sgt. Michael Bernhardt recalled. “We met no resistance and I only saw three captured weapons. We had no casualties. It was just like any other Vietnamese village — old Papa-san, women and kids. As a matter of fact, I don’t remember seeing one military-age male in the entire place, dead or alive. The only prisoner I saw was about 50.”

Thompson had witnessed a soldier kill an injured Vietnamese woman from his vantage point, and then noticed the ditch filled with bodies. "It looks to me like there's an awful lot of unnecessary killing going on down there. Something ain't right about this. There's bodies everywhere,” he said over the radio. He landed and got into a confrontation with platoon leader Lieutenant William L. Calley.

After taking off again, the pilot witnessed soldiers chasing civilians and landed the helicopter between them. He evacuated the villagers and returned to the scene to search for survivors. Thompson also told his superiors about the massacre, and the order was sent back to “knock off the killing.”

“After the shooting was over, the soldiers went and were eating their lunch, really literally next to the ditch, next to the bodies. And that’s how disconnected you get,” Seymour Hersh, the investigative reporter who uncovered the story, said on Democracy Now.

COVER UP

Despite Thompson filing a report, a military investigation found there had been no massacre. Captain Ernest Medina, who had ordered the soldiers to be aggressive in their operations, told superiors the unit had killed lots of VC fighters.

'They were hectoring. They didn’t do reporting': #SeymourHersh blasts media over 'Russian hacking' stories https://t.co/jy9sHEGUCspic.twitter.com/PQzP3pXjRa

— RT (@RT_com) January 26, 2017

In 1968, Ron Ridenhour, an infantryman who had heard about the event, started investigating what happened. In March 1969 he wrote a letter to President Richard Nixon, the Pentagon, members of Congress, the State Department, the Joint Chiefs of Staff detailing the massacre. This sparked official investigations and Ridenhour, Medina, Thompson, and Calley were interviewed.

Sgt. Ron Haeberle, a US Army photographer with Charlie company, had captured events on official and personal cameras. He handed over the official army rolls of film, but held onto his personal, more graphic ones, later explaining he thought they would have been destroyed.

Hersh, then a freelance journalist in Washington, heard what happened at My Lai from an antiwar lawyer, and started to speak to those in the unit. He saw a news report about Calley being charged with murder in September 1969, and managed to get hold of the classified charge sheet. Hersch’s resulting report, “Lieutenant Accused of Murdering 109 Civilians,” appeared in the Dispatch News Service on November 13, and was picked up by a number of publications before gaining further traction.

In November, a selection of Haeberle’s images were published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. The photographs backed up Thompson's claims and helped with the investigation. Years later, Haeberle admitted he destroyed the most graphic images of soldiers killing the villagers. "I had actual photos of actual guys who were doing the shooting and stuff like that,” he said.

On November 15, half a million anti-war protesters marched in Washington, with a march also taking place in London at the same time. In 1973, direct US troop involvement in Vietnam ended.

A 1970 inquiry by Lieut. Gen. William Peers into the My Lai cover up found “at every command level from company to division, actions were taken or omitted which together effectively concealed from higher headquarters the events which transpired.”

Calley’s court martial ended 1971. He was found guilty of killing 22 people and sentenced to life at hard labor. However, President Richard Nixon intervened, and he was placed under house arrest instead before being freed in 1974. "There is not a day that goes by that I do not feel remorse for what happened that day in My Lai," Calley admitted in 2009.

Video by Sergio Angulo