The Pentagon spent $334 million to stockpile an anthrax drug for a possible elaborate bioterrorist attack. The drug was produced by a company with a top government advisor on its board who’s been warning decision-makers about such a threat for a decade.

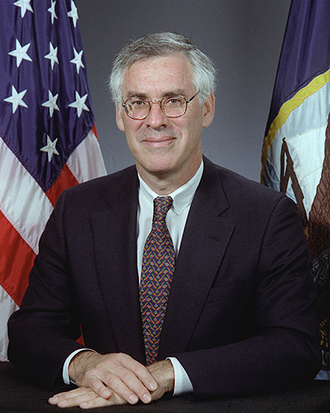

Richard J. Danzig, former secretary of the Navy, a prominent lawyer and biowarfare consultant to the US government, was involved with Human Genome, a biotech company. He received more than $1 million in director's fees and other compensation from the company between 2001 and 2012, reports the Los Angeles Times.

Over the decade he was a strong advocate of improving America’s capability to respond to a possible bioterriorist attack. One of the scenarios he was warning about involved terrorist creating a strain of anthrax resistant to common antibiotics and weaponizing it.

He had the ear of senior Pentagon and DHS officials, with the government eventually deciding to stockpile drugs to deal with such kind of anthrax. One of them called raxibacumab, or raxi, is produced by Human Genome.

It was the first product that the company managed to sale and the US government is the only customer, the newspaper says. The US ordered 20,000 doses of raxi in 2006 and 45,000 more doses after 2009, when the initial batch expired. At shelf price of $5,100 per dose, the company received $334 million for the product, the newspaper says.

The LA Times spoke to seven former top US officials, six of whom said they had no knowledge of Danzig being on board of the firm. One of them, Dr. Philip K. Russell, who helped the US prepare for biological attacks during the George W. Bush administration, said "Holy smoke—that was a horrible conflict of interest," when the newspaper explained the situation.

Danzig said in an interview that no such conflict existed and that he had acted “very properly.”

"My view was I'm not going to get involved in selling that," Danzig told the newspaper. "But at the same time now, should I not say what I think is right in the government circles with regard to this? And my answer was, 'If I have occasion to comment on this, it ought to be in general, as a policy matter, not as a particular procurement.’”

Danzig started sounding the alarm about possible anthrax terrorist act after the widely-publicized 2001 attack, in which anthrax-laced letters killed five people and infected 11 others. In 2008, the DoJ named senior biodefense researcher Bruce Edwards Ivins, who had died a month earlier, as the sole suspect in the attack, but no formal trial was ever conducted.

While the anthrax powder used in the 2001 attack was not resistant to antibiotics, Danzig said it would be “quite easy” for terrorists to create one. "Even at the high school level, biology students understand that an antibiotic-resistant strain can be developed," he wrote in his key policymaking 2003 report "Catastrophic Bioterrorism - What Is To Be Done?"

But the notion is not shared by some microbiologists.

"It's not a trivial endeavor," Paul Keim, a Northern Arizona University geneticist and anthrax expert, told the newspaper. "This is something beyond the capability of a high school student or even someone with graduate training."

Keim added that if anthrax were made resistant to antibiotics, it would decrease the bacteria’s stability and virulence, greatly reducing its lethality.

Human Genome was acquired by the British drug giant GlaxoSmithKline last year for $3.6 billion.

Raxi was tested only on animals, since the lethality of anthrax does not allow for clinical trials on humans. Luckily, no terrorist group has used anthrax – antibiotic-resistant or otherwise – for a massive attack, which would put US stockpile of raxi to good use.