Prosecutors ‘coerce’ drug offenders into waiving their right to trial – human rights report

US federal prosecutors often threaten drug offenders with decades of prison time in an effort to intimidate them into waiving their right to trial and agreeing to plead guilty, a Human Rights Watch investigation has determined.

A whopping 97 percent of federal drug defendants agree to a plea bargain, foregoing their constitutionally-protected right to a fair trial. Government attorneys convince them to do so by charging a defendant with crimes that have high minimum mandatory sentences attached, meaning a judge has no choice but to follow the pre-disposed guideline.

Human Rights Watch (HRW), a non-governmental organization that lobbies for human rights around the world, found that the three percent of defendants who take their chances with a trial are often disappointed. Federal drug offenders convicted in a trial are given prison sentences that are on average three times longer than those who accept a plea deal, according to “An Offer You Can’t Refuse,” the 126-page HRW report.

“There is nothing inherently wrong with resolving cases through guilty pleas – it reduces the many burdens of trial preparation and the trial itself on prosecutors, defendants, judges and witnesses,” the report stated.

“But in the US plea bargaining system, many federal prosecutors strong-arm defendants by offering the, shorter prison terms if they plead guilty, and threatening them if they go to trial with sentences that, in the words of Judge John Gleeson of the Southern District of New York, can be ‘so excessively severe, they take your breath away.’”

One of the most flagrant examples of alleged prosecutorial overreach is the case of Darlene Eckles. In 2002, Eckles was a single mom who was balancing college courses and a full time job when she took in her homeless brother into her home in an effort to keep him off the streets. She told police that one day, upon arriving home from class, she noticed that her brother – who had a history of drug dealing – was counting money in the living room.

“I’ll help you count it, then I want you to get out,” she said, as quoted by Utah’s Deseret News.

Yet by then police had already been monitoring her brothers for months and Ms. Eckles was soon arrested as part of a 37-member conspiracy. Responsible for raising a young son, Eckles refused a 10-year prison sentence only to be sentenced to 20 years after a trial. Her brother, the ringleader of the drug ring, testified against her at trial and received less than 12 years.

Experts say that drug cases likes Eckles’ have become the norm, not the exception to the rule.

“If we want to solve this problem in our community, we have to stop locking everyone up,” said Jeffrey Goodwin, a magistrate judge in the 10th District of North Carolina. “Incarceration doesn’t just affect that person. It doesn’t just affect the immediate family of that person. It affects extended family members, who may be asked to care for children. It affects the entire community.”

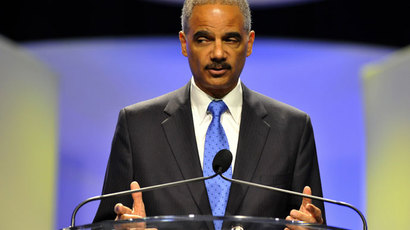

US Attorney General Eric Holder announced in August that he had directed federal prosecutors to cease charging defendants in a way that automatically sets off a mandatory minimum sentence.

For instance, an offender accused of conspiring to sell five kilograms of cocaine could be hit with a 10-year mandatory minimum if the prosecutor wrote that “the defendant conspired to distribute cocaine” without indicating exactly how much cocaine that person was actually carrying.

Holder admitted that such technicalities mean prosecutorial discretion will still be a major factor in sentencing, saying “widespread incarceration at the federal, state, and local levels is both ineffective and unsustainable.”

Jamie Fellner, the author of the HRW report, put the situation more simply.

“Prosecutors give drug defendants a so-called choice – in the most egregious cases, the choice can be to plead guilty to 10 years, or risk life without parole by going to trial,” she said. “Prosecutors make offers few drug defendants can refuse. This is coercion pure and simple.”